An Indian mining conglomerate is eating up a sacred forest grove

In early September, along with three other farmers from his tribal clan, Mangal Sai offered the first grains of his rice crop to the deity Bada Dev. Each year, this ritual marks the festival of Nava Khai: Only after thanking God for the harvest will the farmers reap its bounty.

In early September, along with three other farmers from his tribal clan, Mangal Sai offered the first grains of his rice crop to the deity Bada Dev. Each year, this ritual marks the festival of Nava Khai: Only after thanking God for the harvest will the farmers reap its bounty.

But Bada Dev had a new address this year. For generations, Sai’s family has observed this ritual at a sacred grove of Sal trees in their ancestral village of Hariharpur, which lies inside the Hasdeo Arand forest in the central Indian state of Chhattisgarh.

Now, though, the tall, slender trees are part of “Parsa East and Kanta Basan,” an expanding coal mine that opened in the forest in 2013. The project is owned by a state-run electricity generator, Rajasthan Rajya Vidyut Utpadan Nigam (RRVUNL), which has contracted all mining operations to the Adani group—an Indian conglomerate with an annual revenue of $13 billion.

The layer of coal in the region is too shallow for underground mining, so Parsa East and Kanta Basan is an open-pit mine: excavated from above, digging into the land near the sacred grove. Amid resistance from Sai’s clan, Adani has not felled the trees. But it has excavated the area around it—turning the holy site into an island surrounded by deep trenches.

“An Adani official had earlier told us they would leave a way” to walk to the grove, said 52-year-old Sai, a member of the Indian forest tribe Raj Gond. “But now the company is saying it will cut down our trees.” The official, Reetesh Gautam, who is a general manager at Parsa East and Kanta Basan, told Quartz he has no recollection of a sacred grove at the mine.

Earlier this year, Sai waded through the pit and brought back some mud from the grove. A priest deposited it under another grove of trees near the edge of the mine. This is where the clan celebrated Nava Khai this year.

Coal 1, forest 0

Hasdeo Arand is the largest uninterrupted tract of forest in central India outside of places like national parks, which are shielded from industrial activity by wildlife protection laws. Though the forest sits atop an estimated 5,500 million tonnes of coal, it had been left largely undisturbed; Parsa East and Kanta Basan is only the second coal mine in the region.

During the mine’s 34-year lifespan, around 370,000 trees will be felled. When forest land is destroyed for a project, Indian laws require saplings to be planted over twice as much area elsewhere. But activists say that damage due to the loss of biodiversity as well as the displacement of Hasdeo Arand’s tribal population will be irreparable.

“The tribal villagers rely on the forest for food, medicines, worship, and their livelihoods. Losing the forest would mean losing their entire culture,” said Bipasha Paul, a program officer at Janabhivyakti, a non-profit that opposes coal mining in Hasdeo Arand.

Meanwhile, Adani is hoping to start two new coal mines in the forest: Kente Extension and Parsa. The Indian government allotted rights for both of these to RRVUNL, which contracted them to the Adani group even before the projects receive clearances related to environment and deforestation.

Parsa East and Kanta Basan was the first Indian coal mine to be run completely by a contractor, but the business model is expanding rapidly. Adani alone has amassed nine such deals—all from state-run companies—becoming the market leader in an industry that’s estimated to grow to $8.5 billion by 2030. One of the group’s self-professed specialties is getting clearances from the government; anti-mining activists note Adani’s perceived closeness to prime minister Narendra Modi.

An example of muddled consent

A small part of Sai’s village, including the grove, had already been allocated to the existing Parsa East and Kanta Basan mine. Now, the rest of the village will also be dug up for the proposed Parsa mine, which secured an environmental clearance from the national government in July.

One legal opinion is that, according to India’s village governance laws, Parsa needs the consent of a majority of the tribal villagers who will be displaced due to the project. While RRVUNL and the Chhattisgarh state government have argued that the project is exempt from this consent clause, they did not take any chances.

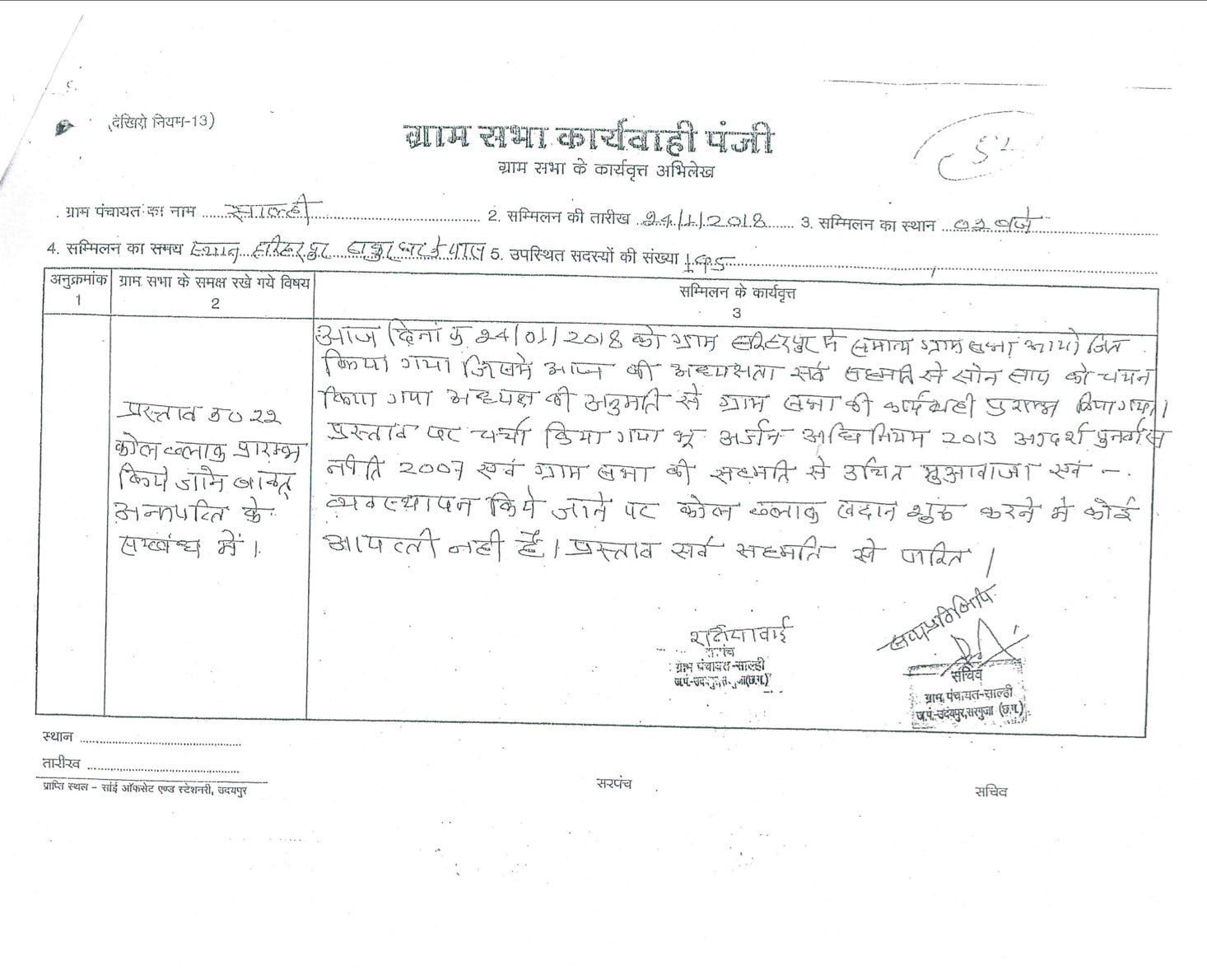

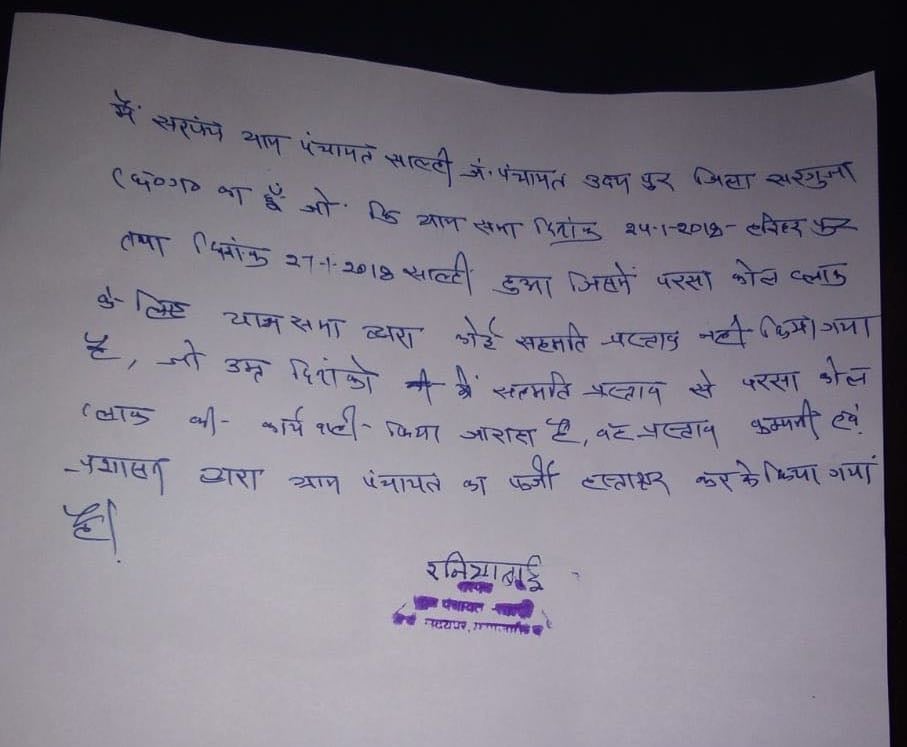

In 2018, the state government—at the time controlled by Modi’s party—submitted before the environmental clearance appraisal committee a consent letter signed by Raniyabai, the elected head of Sai’s village, claiming that residents had expressed “no opposition” to the proposed mine in a public hearing. When the letter was later made public, the village head claimed that she had never signed off on it.

Activists and villagers have filed a complaint at the local district administration office. But few of them are expecting the government to launch a probe into the alleged forgery.

If Parsa obtains its final clearance for tree-felling, Sai would be entitled to compensation and rehabilitation for the loss of his home and farm, for which he has ownership documents. But his clan’s deeper relationship with the forest is not protected. Without the legal rights to their sacred grove, they cannot claim compensation for its imminent destruction.

When asked for comment, a spokesperson for Adani said questions should be directed to RRVUNL, the mine’s owner. RRVUNL did not respond to requests for comment.

Sooner or later, Adani will expand the mine even further—disturbing even the makeshift spot for worship by cutting down the trees sanctified with mud. And if the original grove is also gone by then, there won’t be any more of the mud left to make another shrine for Bada Dev.