The stories seem to follow a script. Countries declare lockdown, and within 10 days, calls to helplines see a spike.

Women call in distress because they or their children are being abused at home, with or without physical violence. It happened in China, then as the Covid-19 pandemic spread to Europe, the “Shadow Pandemic” (as UN Women calls it) spread to Italy, Spain, France, UK, and finally to the US.

Several commentators, (including myself), had raised concerns at the start of the lockdown that confinement at home with an abusive partner is likely result in greater physical and emotional violence against women, with disastrous consequences for their health and well-being.

Earlier evidence from Europe has shown that domestic violence increases whenever families spend time together, even during happy and festive occasions, such as Christmas, Thanksgiving, and family vacations. A lockdown, induced by the apocalyptic scenario of death and disease, is the exact opposite of a happy occasion; why should we expect abuse to follow a different pattern? Indeed, it doesn’t. The lockdown provides the perfect opportunity to the abuser to practice “intimate terrorism”—dictate and control all actions and movements of women, with violence if needed.

The increased violence is not just a result of the frustration due to physical confinement. The pandemic has brought in its wake a global slowdown, massive economic dislocation, closed businesses, the spectre of looming unemployment, often accompanied by the threat of hunger and poverty for what seems to be an indefinite future. While both men and women are affected by the economic downturn, there is evidence from the past that violence against women increases during episodes of high unemployment.

Is India different?

There is evidence for India that alcohol consumption by men increases violence against women, both inside and outside the home. In principle, therefore, any increase in the total cases of violence induced by confinement, stress or unemployment could be offset by reduced incidents of street violence, as well as reduced alcohol-fuelled violence. There is also a view that the joint family system could protect Indian women against domestic violence, a protection not on the cards for western women.

The public concern about violence outside the home, which results in advice to women about how they should dress and stay off public spaces, obfuscates the enormity of intimate terrorism—violence inside homes, by husbands, fathers, uncles, including in joint families. Accounts of survivors reveal how other women in the family either watch helplessly or condone/minimise/ignore the abuse. This abuse, because of its location (inside the home) and its perpetrator (a close relative), is widely underreported. Women who are brave enough to complain about domestic violence represent the tip of the iceberg.

With these caveats in mind, the first set of numbers from complaints made to the National Commission for Women (NCW) is telling. We need to remember that NCW receives very few complaints—most people tend to contact the police first. Thus, these numbers are massive underestimates, over and above the larger issue of domestic abuse being under-reported. However, police data is made available to the public with a huge lag, hence this is the best we have right now.

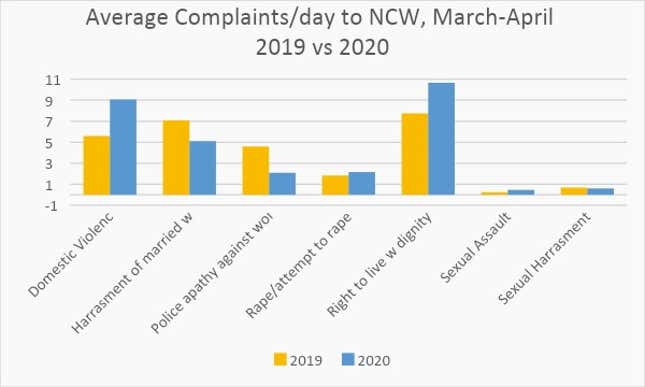

Comparing figures for March–April 2019 to March 2020 and April 1 to 13, I calculated the average per day complaints. These comparisons are very rough. As the lockdown proceeds, it is likely that rest of April sees a further spike, with rates higher than last year.

The chart shows that there is already a sharp jump in complaints related to domestic violence and the “right to live with dignity”, and a smaller increase in rape/attempt to rape and sexual assault. The last two charges are telling, as this number covers two weeks of complete lockdown (therefore no movement outside the home), and reduced mobility in March due to fear of infection. Thus, these rapes and assaults include those perpetrated by family members.

India, unfortunately, is not an exception to the global trend of increased pandemic induced domestic violence.

Sex-selective abortions

In societies with deep-rooted son preference such as ours, there are other serious dimensions of violence against girls. One of these is sex-selective abortion. On April 4, the ministry of health and family Welfare, via a gazette notification, suspended some key sections of the PCPNDT Act (Pre-natal and pre-conception diagnostic techniques Act, 1994) till June 30. This Act makes fetal sex determination illegal. As women’s organisations have pointed out, this weakening of the Act was completely unnecessary. It will only make it easier for families with deep-rooted son preference to freely exercise their prejudice against the girl child.

What, if anything, can be done?

One of the big myths about domestic violence is that it is greater among poorer sections. The reality is that rich and middle-class women are not immune from it. Helplines, shelters and legal assistance for victims of abuse are woefully inadequate at the best of times. With the sudden lockdown, when women find themselves isolated, alone and vulnerable, what are their options? Virtually none.

The first step is for administration and law enforcement agencies to recognize the gravity of the problem, to believe women. Reaching women in distress needs to be classified as an essential service. Women need safe spaces where they can be shifted if needed. Providing safe spaces away from the abuser, if necessary, by converting empty hotels into temporary shelters in urban areas, is of utmost urgency. In rural areas, frontline health workers need to be the first point of contact for abused women, with panchayats and women’s self-help groups working jointly to provide safety and security to women.

Now, not later

As we take all the necessary steps to flatten the pandemic curve, we need to be equally vigilant to make sure that shadow pandemic curve of intimate terrorism does not rise exponentially. This is not a matter of pitting one curve against another. As some of us argued in a recent policy brief, we are in this situation for the long haul. Women’s lives can’t be put on hold till we emerge out of the pandemic.

We welcome your comments at ideas.india@qz.com.