India’s Covid-19 vaccine rollout needs to address hesitancy to truly take off

India has kicked off the world’s largest Covid-19 vaccination programme, but the shadow of rushed approvals persists.

India has kicked off the world’s largest Covid-19 vaccination programme, but the shadow of rushed approvals persists.

Hesitancy over the safety and efficacy of Covaxin, India’s homegrown coronavirus vaccine developed by biotechnology firm Bharat Biotech and the Indian Council of Medical Research, has led to fewer people turning up for their shots.

India began its vaccination drive for frontline and healthcare workers on Jan. 16, and has inoculated 631,417 people in four days. Two vaccines, Covishield, manufactured by Serum Institute of India using the Oxford-AstraZeneca’s master seed, and Covaxin currently have emergency use approval in India. India will also begin exporting the Covishield vaccine today (Jan. 20) to neighbouring nations like Maldives and Bhutan.

Of these two, Covishield was granted approval based on data from the UK drugs regulator, while India-specific bridging trial study data are still pending. Covaxin has no efficacy data because the third phase of its clinical trial is still underway.

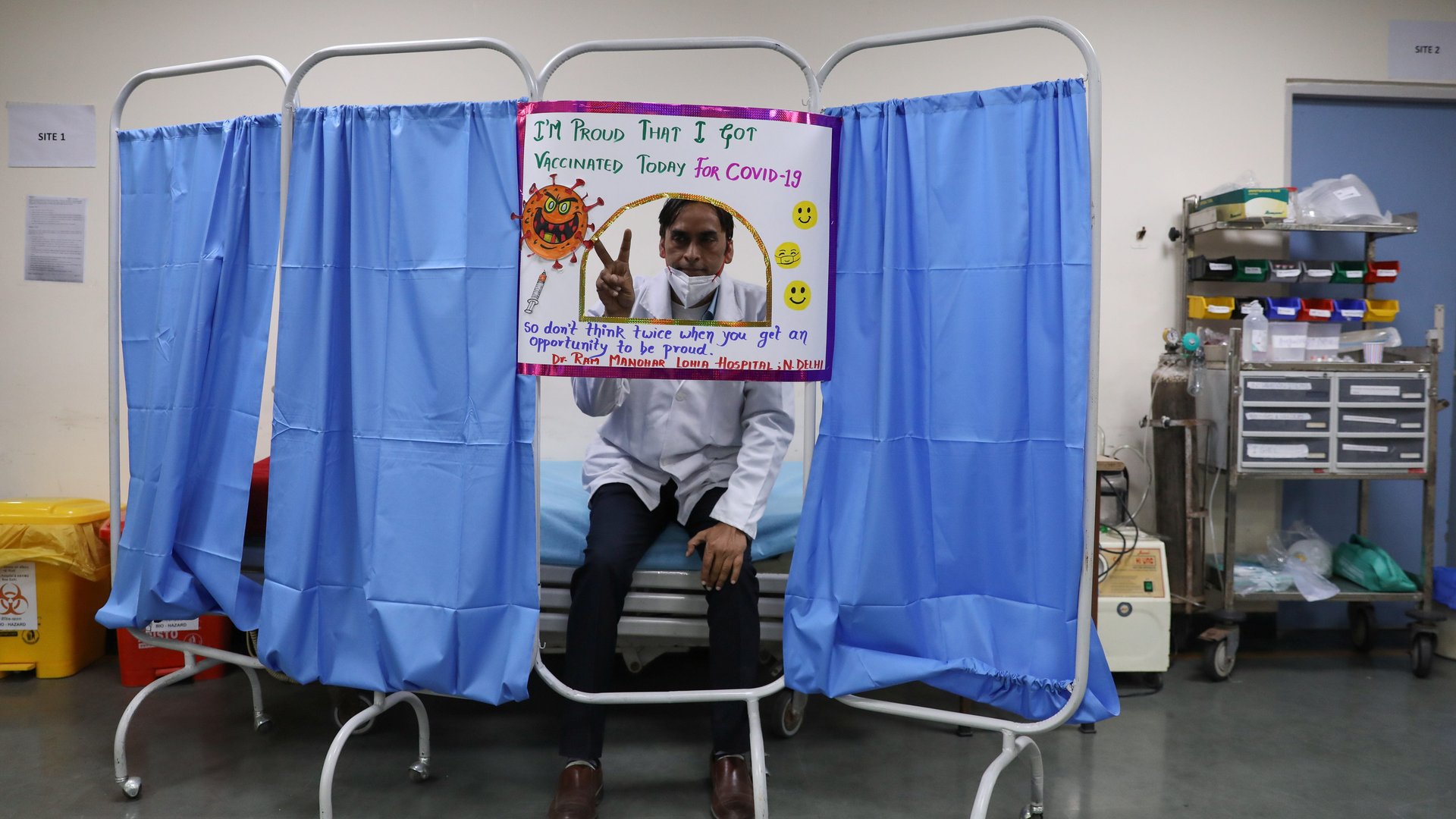

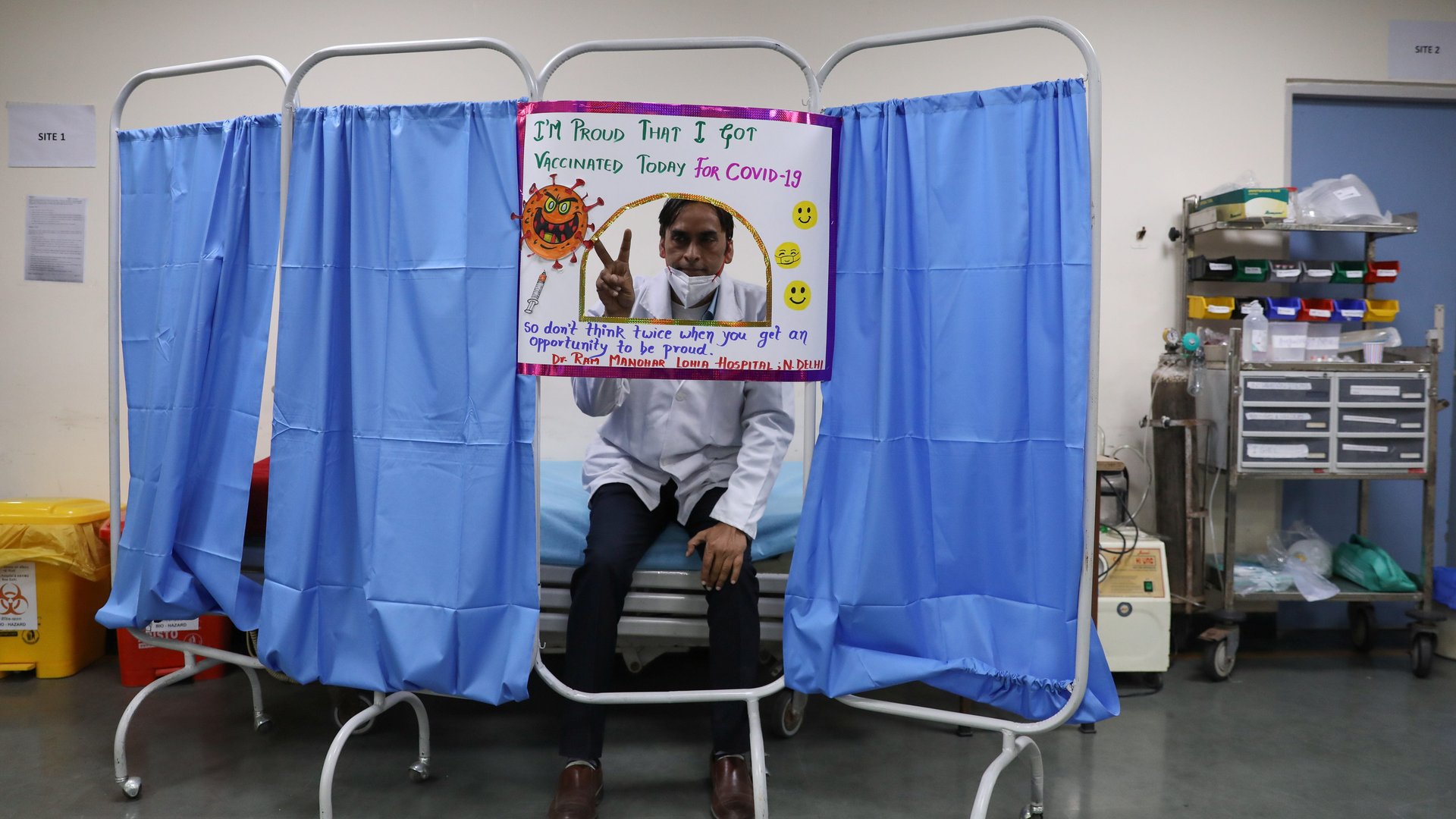

Healthcare workers have expressed concern over being administered shots of Covaxin. For instance, in Delhi’s Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital, resident doctors asserted their desire to take only the Covishield vaccine instead of the Covaxin that was on offer.

Such hesitancy has led to lower turnout from healthcare and frontline workers, especially in large metropolitan cities in the country. In Delhi, for instance, only eight people were vaccinated at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), India’s leading public healthcare institution, on Jan. 18, a source-based report said.

This despite AIIMS director Randeep Guleria being among the first to take the vaccine in the country. Several senior doctors and private hospitals have advocated for the use of the vaccine on social media and elsewhere.

But as of yesterday (Jan. 19), Delhi has consistently vaccinated about half of its daily target of roughly 8,000 healthcare and frontline workers per day.

A vaccine trust deficit

In other parts of the world, including the US, doctors have been hesitant to take vaccines that have not yet been fully tested. “Whatever is happening right now, the kind of response from we’re seeing from workers listed for the vaccines, especially Covaxin, is a sign that the government has dropped the ball on this issue,” says Sulakshana Nandi, national joint convener of the Jan Swasthya Abhiyan, the Indian chapter of the People’s Health Movement. “Such hasty approvals have resulted in a mistrust of the Covid-19 vaccine,” she says.

India’s scientific community has spoken out against rushed vaccine approvals and has questioned the government’s decision making that was based on limited facts and data. For instance, Covaxin was given clearance by India’s drugs regulator under “clinical trial mode,” with no clarity on what that meant.

Besides the lack of clarity on approvals, distrust is also stemming from the allegations against Bharat Biotech for violating consent norms during the phase 3 trial recruitments. “The Indian government has tried to elicit support from the WHO and people like Bill Gates. But this vaccine rollout, under these circumstances and conditions, will go down as an unfortunate event in the history of India’s Covid-19 response,” Nandi says.

Guleria of AIIMS believes that this vaccine hesitancy among healthcare staff is because of the “infodemic” against the coronavirus vaccines in India. “Initially, healthcare workers were very keen to get the vaccine. But then because of the infodemic, because of things doing the rounds on social media, because of side effects being highlighted more than what they were, it created a lot of anxiety not only among healthcare workers but also in public at large,” he told Hindustan Times newspaper.

What has also not helped build trust is the number of adverse events following immunisation (AEFIs) that have been reported.

The adverse events

On Jan. 18, the Indian health ministry had reported a total of 580 AEFIs. These included mild cases of pain on the site of the jab, nausea, headache, and general fatigue, as well as serious symptoms like breathlessness and chest pain. So far, nine cases of AEFIs have required hospitalisation, and none were reported after Jan. 18.

Currently, India has less than 200,000 active Covid-19 cases, and over thrice as many people have been vaccinated. This is also the reason doctors would rather wait a while before getting the jab.

“Many of us have already suffered from Covid and hence we’re not willing to take vaccines unnecessarily. We want to wait for safety and efficacy data,” an unnamed doctor from AIIMS told ThePrint.

Since March, 152,718 Indians have lost their lives to the pandemic. Nandi believes that unlike the US or the UK, where cases and fatalities are on the rise again, India could have waited a while before granting the approvals. “After the questions raised by scientists, the government should have ideally rolled back the approval, especially since it could afford to wait given that the number of cases was declining,” Nandi says. India recorded its lowest number of fresh Covid-19 cases in seven months yesterday (Jan. 19). “A few more weeks and the availability of the efficacy data could have avoided this whole situation.”

Others have argued that this vaccine rollout comes at an appropriate time, allowing large sections of the population to build immunity against the novel coronavirus, especially when the healthcare systems are not overburdened.

“Vaccination is necessary because you do not know when a second wave can potentially start and various other countries have witnessed a second and a third wave with severe cases or a more infectious strain,” Public Health Foundation of India president K Srinath Reddy told Times of India newspaper.