Has the Covid-19 pandemic effectively ended in India?

When India went into lockdown in March 2020, the fear of Covid-19 swiftly spreading through a densely populated country of 1.3 billion people was dangerously real.

When India went into lockdown in March 2020, the fear of Covid-19 swiftly spreading through a densely populated country of 1.3 billion people was dangerously real.

A harsh lockdown, one of the strictest in the world, created a humanitarian crisis of its own, pushing millions of migrant workers to take arduous journeys back home on foot. But the possible catastrophic impact of the pandemic was considered greater in magnitude by the government.

Nearly 11 months on, the Covid-19 infections and fatalities in India tell a different story.

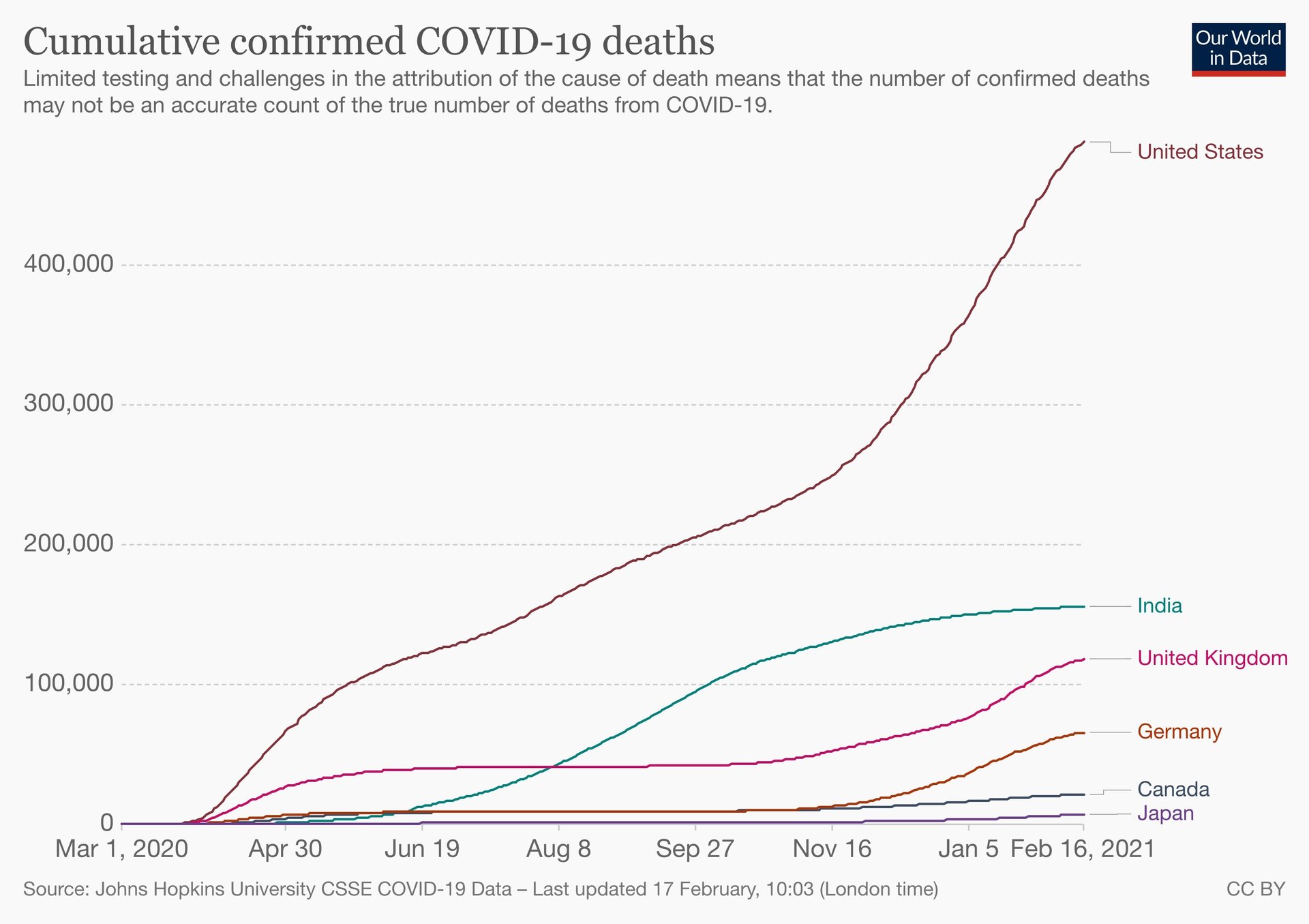

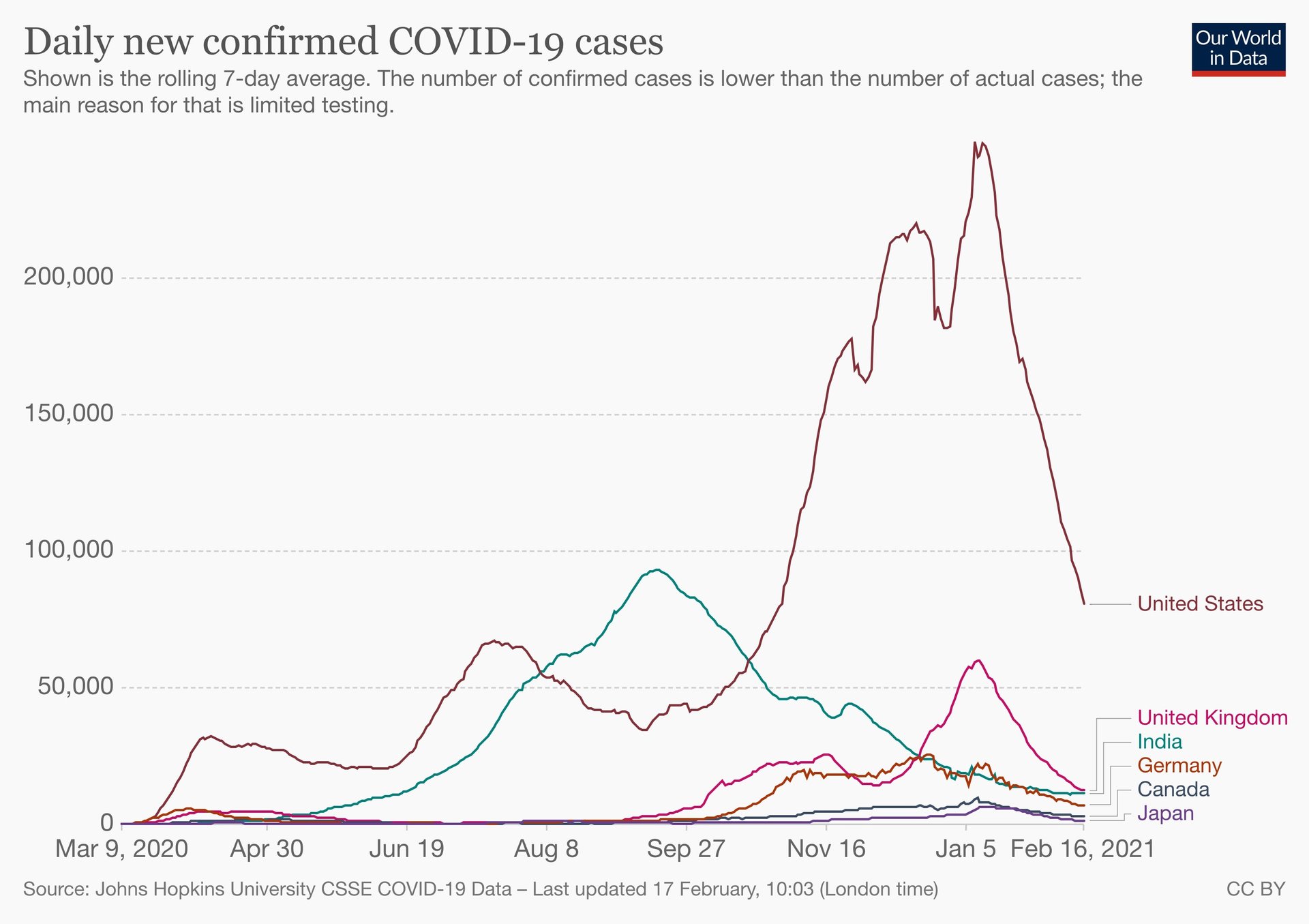

In the early days of the pandemic in the country, for instance, the projected fatalities from the viral infection were believed to be 4 million. But as of Feb. 18, deaths from Covid-19 in India stand at 155,913, less than 10% of the estimate.

“These early figures were based on European parameters, not taking into account India’s young demographic. Even then, my own modified estimate, based on data available at the time, was that Covid-19 deaths could be up to 2 million,” says Jayaprakash Muliyil, India’s leading epidemiologist and the chairman of the National Institute of Epidemiology’s scientific advisory committee.

The new daily Covid-19 infections have also steadily been trending downwards, with 11,610 new cases on Feb. 17. At its peak in September, there were over 97,000 cases of coronavirus infections being reported daily in India.

During the initial months of the pandemic, India was reporting worryingly low levels of testing, raising doubts over whether the government’s figures were reliable, and if the spread of the infection was at all being contained.

At this point, epidemiologists are fairly confident the data on infections, fatality, and testing is reliable, barring minor deviations from available statistics. “Although it is true that Covid-19 testing has slumped recently,” says Gautam Menon, professor at the departments of physics and biology at Ashoka University, other parameters may point to a fuller picture. “Test positivity rates, in most states apart from Kerala and Maharashtra, are low at the moment, below the 5% suggested by the WHO as an indication for how well the pandemic has been controlled. This suggests that the decrease in the numbers, both of cases and deaths, is likely a real effect,” he explains.

Other signs can be found in fewer people turning up at fever clinics and hospitals reporting lower occupancy rates, according to Swapneil Parikh, co-founder of Covid-19 response startup DIY.health and a practising internal medicine doctor.

So in the scenario that the data are reliable, why and how has India managed to contain the pandemic?

Lockdowns and masks

Researchers believe India’s lockdown did help delay the impact of the disease, which in turn helped contain its overall impact on the population. “This [the lockdown] helped in preventing the disease from spreading all at once. Even after the lockdown was lifted, the surge in cases was spread out in different regions over some time,” says Giridhara R Babu, professor and head of life-course epidemiology at Public Health Foundation of India.

There is also a large consensus that the mass use of masks, at least in India’s cities worst affected by the novel coronavirus, has helped bring the numbers down. Prime minister Narendra Modi’s messaging on the need to wear masks has been consistent since he announced the lockdown in March 2020, and wore masks on recorded video announcements to stay on message. His cabinet has also followed mask wearing, and there has been little public pushback against wearing masks.

This is also likely because of the hefty fines that some cities have imposed on citizens for not complying with mask mandates. In Delhi, for instance, during the catastrophic peak of Covid-19 during the months of October and November, the fine for not wearing a mask was increased four-fold to Rs2,000 ($27.5).

In some cases, the Indian Council for Medical Research (ICMR), the country’s nodal body for medical research and the Covid-19 response, sometimes went over and above WHO recommendations. For instance, Indians are supposed to wear masks in all public places, including their own cars even if they are driving alone.

But not everyone complied with mask-wearing and social distancing, despite the regulations. As Muliyil points out, barring the first few months of the lockdown, Indians went about their lives—with political rallies, religious events, weddings, and social unrest—during a pandemic.

Could it then be that Indians had some pre-existing immunity to the virus, at least to the extent of curtailing the instances of severe cases and fatalities?

Mysterious Covid-19 immunity?

It is quite likely that South Asians do have some immunity against the virus, scientists believe. What exactly this immunity entails, who it protects, and against what form of Covid-19 is yet to be determined. But there are some possibilities.

According to Muliyil, the tropical region has reported fewer mortalities, likely because of the abundance of sunshine. This is conversely true for colder countries like the US or those in Europe, which experienced second and third waves of the pandemic during winter months.

He points to research by epidemiologists at the University of Heidelberg in Germany, which implied “that 87% of Covid-19 deaths may be statistically attributed to vitamin D insufficiency and could potentially be avoided by eliminating vitamin D insufficiency.”

Muliyil contends that most Indians, barring urban wealthy and middle-classes, work outdoors and have higher levels of vitamin D that offers them protection against Covid-19 morbidity. “Largely, Indians’ levels of vitamin D are quite impressive, and this has proven to be effective against other viruses too. Thus I am encouraged to believe vitamin D has some role to play in lower numbers of deaths,” he says.

The other factor—and a major one at that—is the younger population in India.

Young people, fewer serious cases

Parikh of DIY.Health says that beyond the overall population of India, its specific demographic differences have helped the country keep Covid-19 in check. “Nearly 40% of India’s population is below 18, and the fatality rate in this age group is 0.001-0.01%,” he says. The most vulnerable population, people aged above 65, are just over 6%.

Socially, older Indians tend not to work beyond the retirement age of 60, and Parikh says this too contributes in some way at reducing the exposure of vulnerable groups.

Those with co-morbidities in India are also likely to be lower in number, which, counterintuitive as it may seem, is a result of poor access to healthcare. “In Western countries, life expectancy is greater and people live longer with diseases like diabetes, cancer, or heart conditions. As a result, there are more people living with co-morbidities, thus increases the chances of fatality,” says Muliyil.

In India, access to medical facilities is a serious constraint for average citizens, and the country has some of the highest out-of-pocket per capita expenditure on healthcare in the world. This makes even treatable and manageable diseases fatal for even the young among those living on the margins, effectively reducing the “density of comorbidities” and thus, the size of the population living with diseases that exacerbate Covid-19.

All of this has helped the case fatality rate in India at around 1.5%.

But it isn’t as if Covid-19 was not catastrophic for India—both in terms of the absolute number of cases and the economy. The country did see a high number of cases, and the highest number of positive cases per million population in the South Asian context.

Given this high number of cases, is it possible India has reached herd immunity?

A plausible case of herd immunity in India

Only a little over 1% of India’s population has officially tested positive for Covid-19. But serological surveys across the country tell a different story.

In densely populated cities like Mumbai and New Delhi, serological testing has shown a prevalence of Covid-19 antibodies in over 50% of the population. This points to a large number of asymptomatic or undetected cases of the infection. In Delhi, for instance, the most recent sero-survey showed 56% of the residents have already developed antibodies. A part of the reason for such a high number of asymptomatic cases could be widespread masking, which has been proven to reduce the severity of the disease.

This is a promising trend that could eventually lead to a scenario of herd immunity, where 70% of the population has antibodies for Covid-19. Antibodies offer protection against re-infection, and leave the virus with no host bodies to circulate. “All initial worries that antibodies won’t offer long-term protection are now not valid. We know that the immunity against the virus after an infection is good and strong,” explains Muliyil.

Pandemics can potentially end because of herd immunity, which is achieved through natural infections, or the protection offered by vaccinations. “The downward trajectory of the disease in India can be attributed to ‘localised’ herd immunity in most urban areas and a predominantly younger population,” says PHFI’s Babu.

In most parts of the country, thus, researchers believe that the pandemic’s trajectory—a sharp rise and then a fall—may well and truly be over. But two worries remain.

First, the new mutations of the virus could potentially lead to a new wave of infections in the country. “In a pandemic, things can change on a dime,” says Parikh.

But researchers believe that the effects of the coronavirus variants found in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK would have been clear by now. “Yes, the new variants do pose a challenge, but we haven’t seen any drastic change in morbidities or severe infections so far,” says Muliyil. He adds that there is now evidence that vaccines can also be re-engineered to target these variants.

The second cause of concern is that while there may be localised herd immunity, the nationwide sero-prevalence is at 20% of the population. While epidemiologists say sero-surveys largely underestimate the population with antibodies, it is still much less than the 70% herd immunity mark.

In this scenario, masking, social distancing, and hand hygiene—the trifecta of social behaviour to fight Covid-19—is likely to remain a reality.