India’s poorly planned vaccination drive is toying with students’ dreams to study abroad

India’s ill-conceived vaccination programme could jeopardise the future of thousands of youth.

India’s ill-conceived vaccination programme could jeopardise the future of thousands of youth.

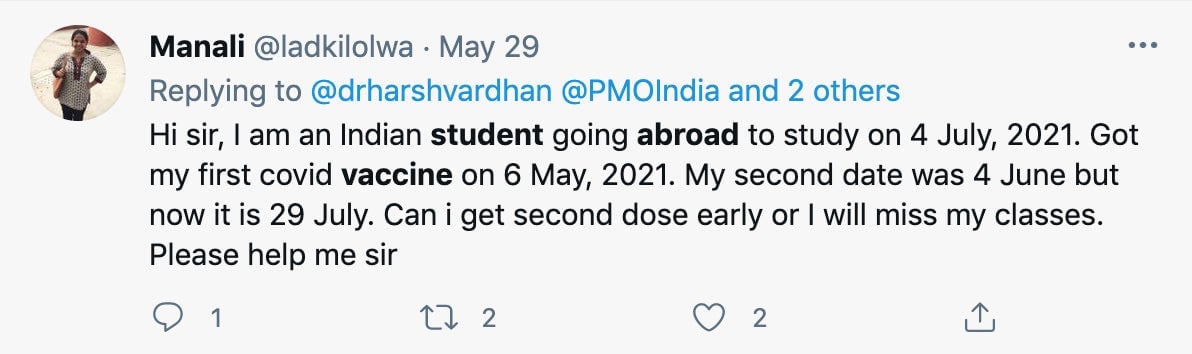

Indian students who are set to attend foreign universities this year are struggling to get vaccinated, which is one of the pre-requisite for entering several countries and attending classes on many campuses.

There is no nationwide rule laid out for such students by the Narendra Modi government. Some states—Kerala, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat—have agreed to give such students a priority, and two major cities, Mumbai and Bengaluru, have also started similar drives.

But so far, these states and cities are struggling to help the students. For instance, in a non-pandemic year, around 60,000 students from Maharashtra travel abroad to study. Right now, the state’s capital, Mumbai, has only three vaccination centres dedicated to students which are administering a meagre 100 doses each daily. Most of these other places that have agreed to prioritise students haven’t yet started vaccinating the cohort.

The biggest problem in the plan is the acute shortage of vaccines across India.

This mismanagement could cost a year for thousands of Indian students. In 2019, over a million Indian students travelled abroad for higher studies. Of this, a majority went to the US, followed by Canada and Australia.

Students scramble for first dose of Covid-19 vaccine

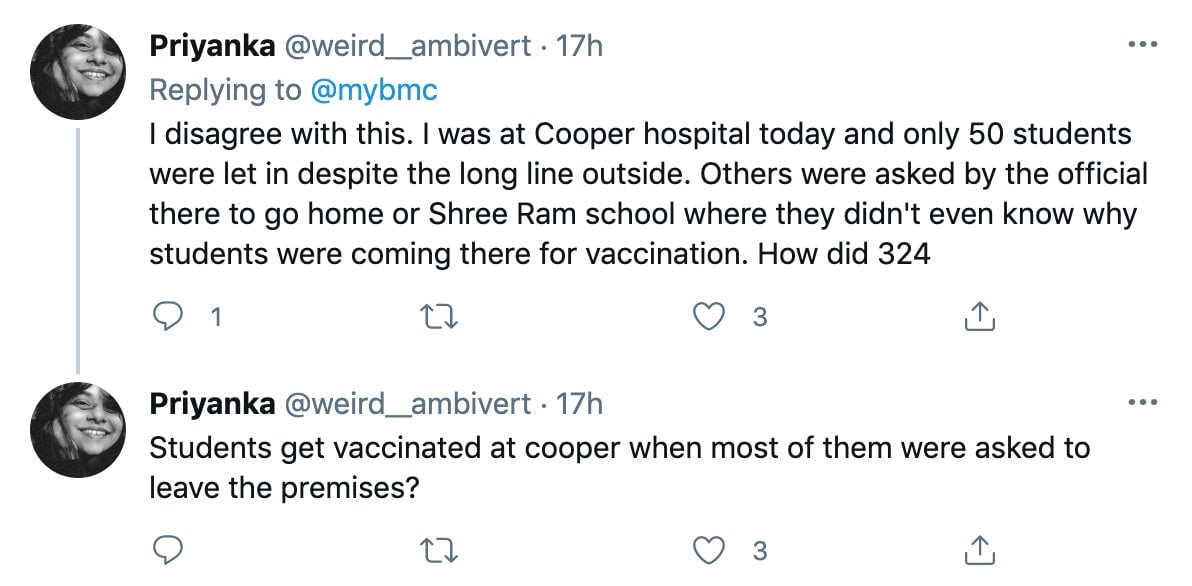

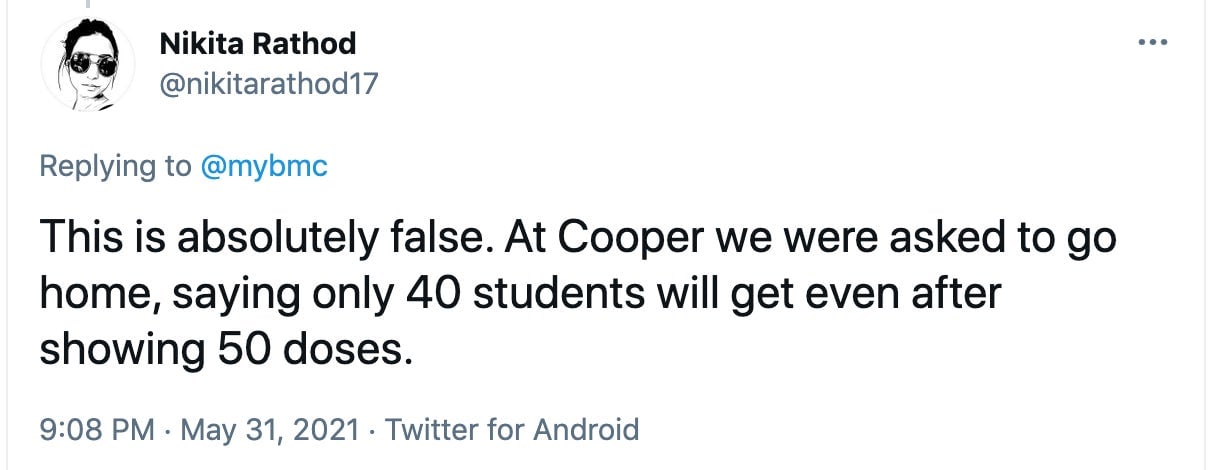

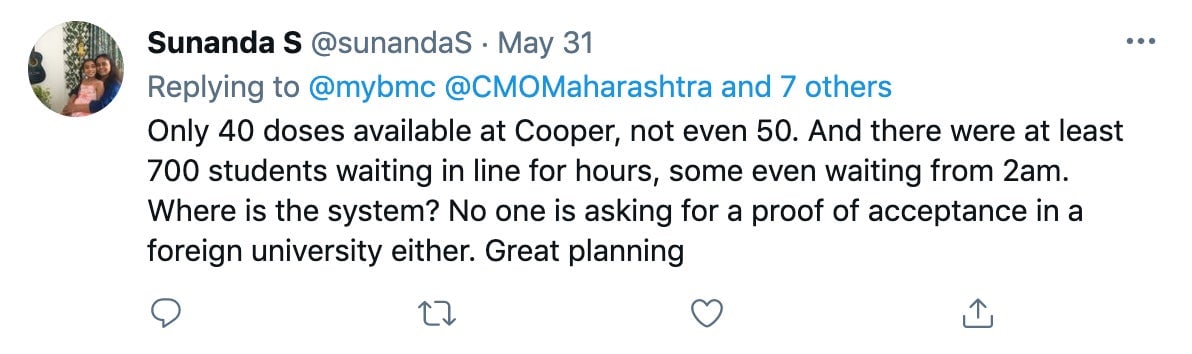

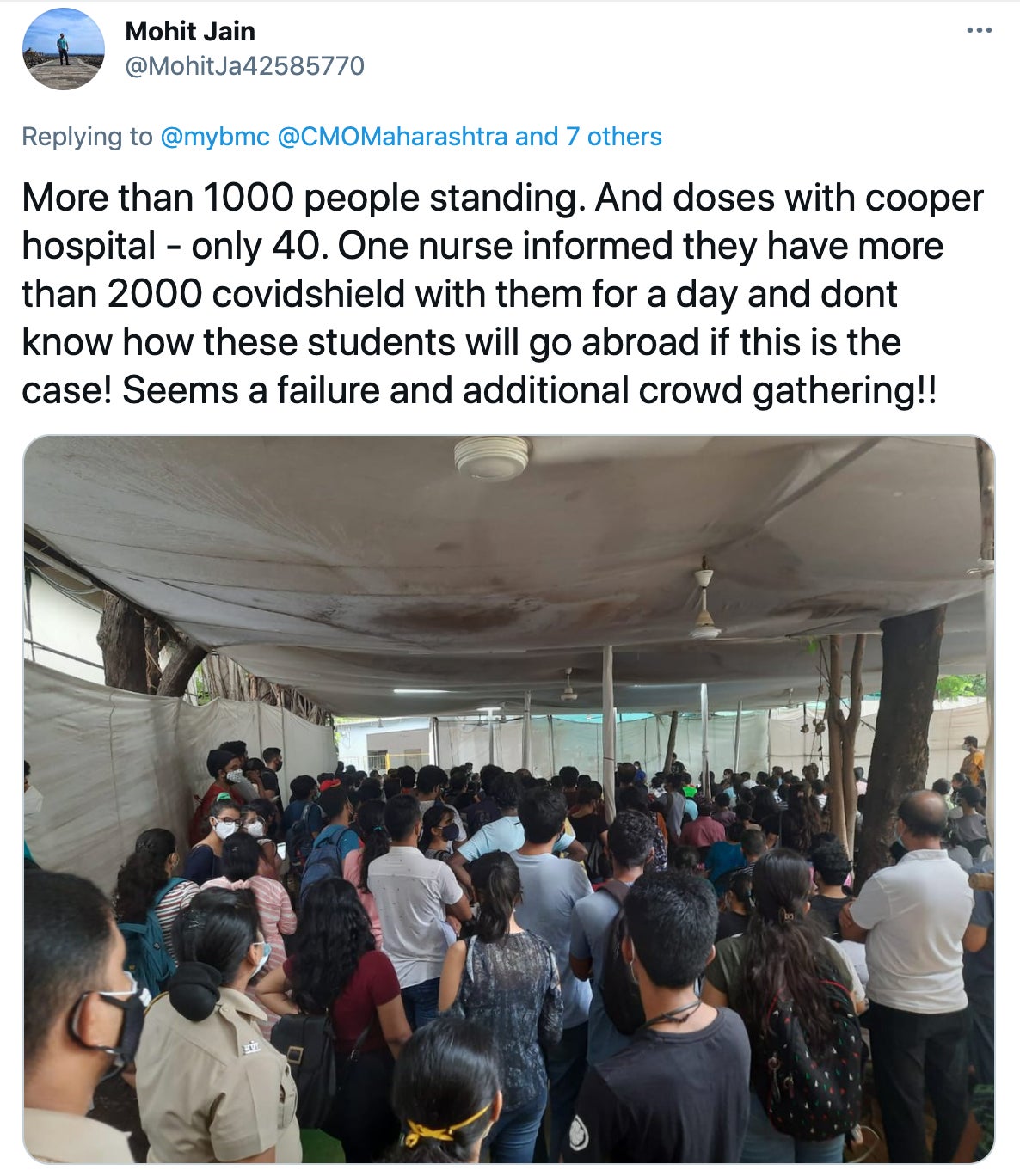

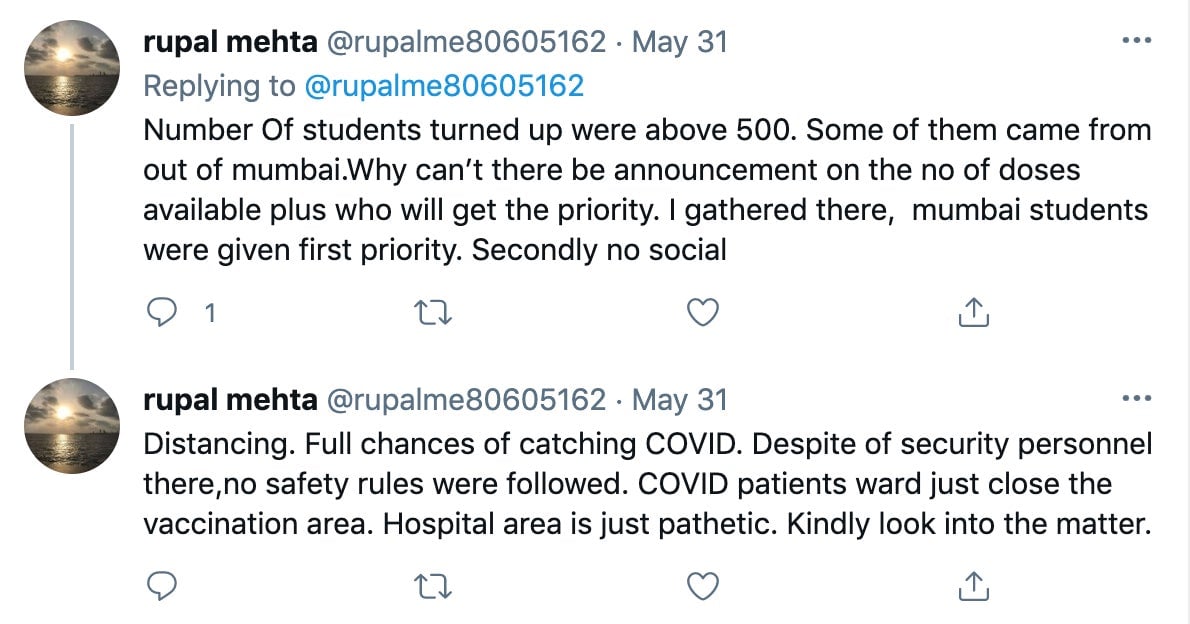

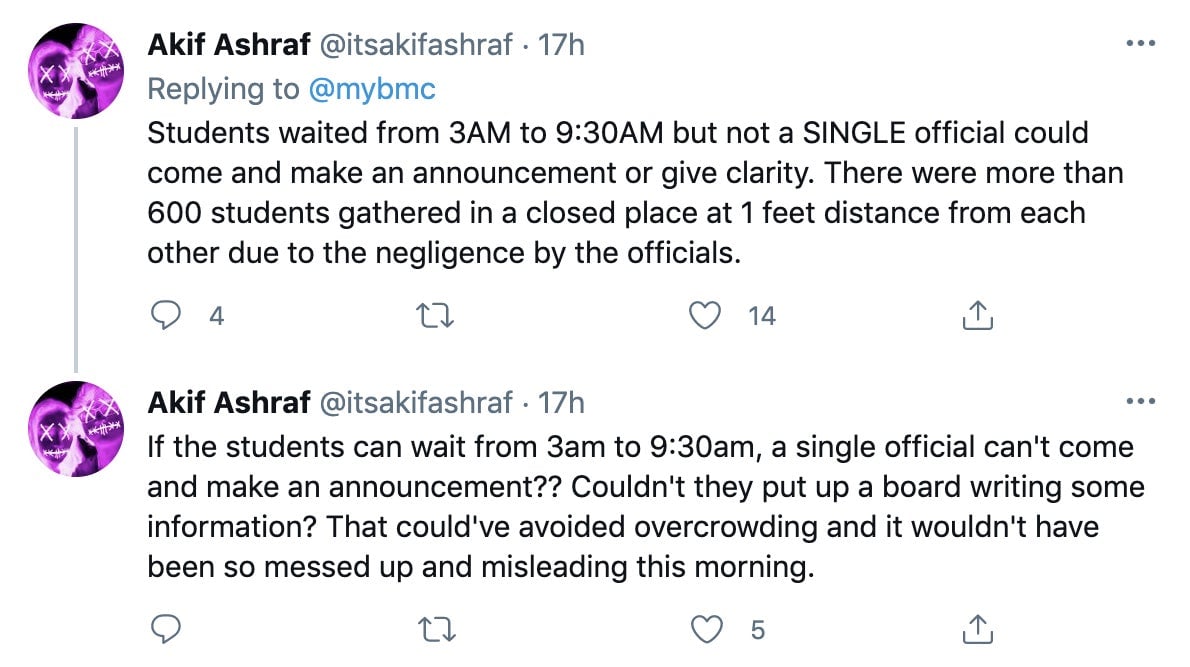

On May 31, the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) claimed 987 students planning to pursue their higher education abroad were vaccinated at Kasturba Hospital (338), Cooper Hospital (324) and Rajawadi Hospitals (325). But Twitter is flooded with messages of disbelief from people who were turned away by centres after waiting for hours.

At Cooper alone, for instance, only 40 doses were available, several students who stood in the queue corroborated. One even alleged that no one was checking the required university admission documents.

At Rajawadi, too, just 50 doses were available while more than 500 students had lined up, several netizens alleged. Among those who were turned away was 26-year-old Sandesh Avhad, who told Quartz that he has been trying and failing to get a slot on the Cowin app for a month now. He said he’d still rather queue outside a centre at 4am than hunt for an appointment online.

Like Avhad, most students were told to go back home after waiting for three or more hours. Those who turned up for their shot were disgruntled not just by the lack of clear communication, but also by a gross violation of Covid-19 protocols of social distancing.

Even those who managed to get the vaccine said the process was rushed and laden with mistakes.

Kavya Nair, who got her jab at a centre in Andheri West, Mumbai, on May 31, noticed the workers at her centre made a mistake in her father’s name, despite it being clearly mentioned on the vaccination form and her Aadhar card. “When I went to rectify the error, the nurse told me, ‘you can do that when you come back for your second dose.’ And it’s not just me, but many who are facing this issue. Some have mistakes more damning than mine,” Nair, who is heading to the UK for her second master’s in health psychology, told Quartz.

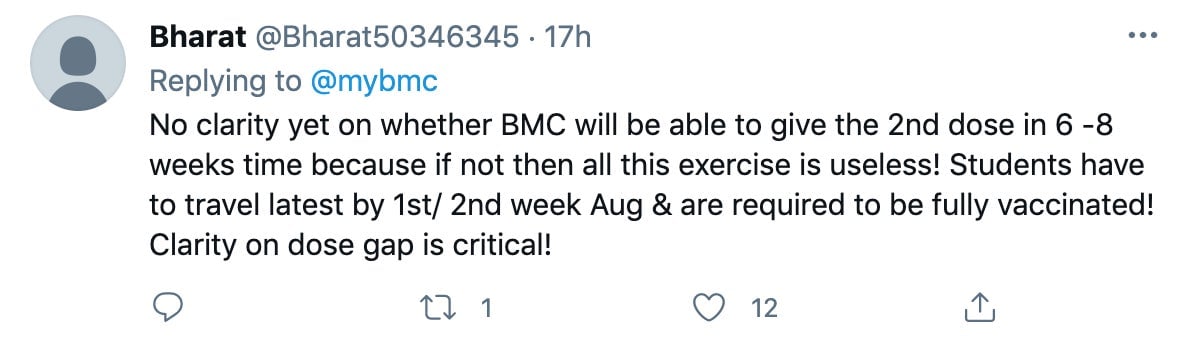

Even for those who managed to get the first jab, getting the second one is likely to be a big hurdle.

Students stress about Covishield’s second dose

India’s vaccination programme currently depends mainly on two vaccines: the indigenous Covaxin and Covishield, which is the local name for the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine.

Of the two, Covaxin is currently not recognised by the World Health Organization, and most international universities also do not accept the vaccine. This vaccine has a four-week window between two doses, which means if it was acceptable, students could get both the shots in time for their semesters.

Covishield, which is internationally recognised, has a 12 to 16 weeks gap between doses. And with most semesters starting around August, an 84 day waiting period for the second dose is not feasible for many students.

For Siya Khanse, who is pursuing her masters at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh in the US, the situation is even more complicated. Since she got Covid in April, she can’t get even the first dose until July as the Indian government has mandated a three-month gap for those who have recovered from the disease to get vaccinated.

With this long window, she’ll never make it in time for her September session. Her university is running vaccination drives on campus but until she gets both doses, she won’t be able to attend classes in person despite being in the country.

Some states are trying to ease this hurdle. For example, the Kerala government will allow those traveling overseas for work and higher studies to take the second dose of the Covishield vaccine four to six weeks after the first dose. On June 1, politician Priyanka Chaturvedi wrote to the centre to reduce the gap between doses for students travelling abroad for further studies. But there’s no clarification on this from the Indian government.

As the rules vary from state to state, even from district to district, the nerves are far from calm.

A Bengaluru resident headed to Columbia University to continue her PhD this fall has been assured by the institute that getting the vaccine is not compulsory for her. However, she’s still trying to get the jabs as soon as possible. ”I get the panic. No one knows how travel rules change month to month. No one knows the rules in transit countries,” the 30-year-old, who wished to stay anonymous, told Quartz.

Several countries are debating ways to verify vaccine statuses to let foreigners in. One solution on the table is a health passport that provides certification of inoculation.

“Even as US and Canada that get the bulk of Indian students do not have a vaccine passport so far, the countries are thinking about it… (the) situation is extremely dynamic and whenever they do decide to go for a vaccine passport, students who are inoculated will be at an advantage,” Sumeet Jain, co-founder of study abroad platform Yocket, told the Print.

Meanwhile, these concessions for students going to study abroad have not gone down well with everyone. Students in India, who will be appearing for exams in the coming months, are up in arms about this decision that moves others ahead of them in the line. “Many of our patients who are in their 30s and 40s, and have got their first jab of Covishield, have to wait at least 12 weeks for the second. It is unfair that the government is showing leniency to select persons,” a doctor in a private hospital told the Hindu.