Exotic holidays, wristwatches, salt and other bizarre goods that India’s public-sector firms produce

Minimum governance has been a favoured mantra of Prime Minister Narendra Modi for some years. Another dictum is to push for economic growth by boosting private enterprise through greater foreign direct investment and divesting government-owned companies.

Minimum governance has been a favoured mantra of Prime Minister Narendra Modi for some years. Another dictum is to push for economic growth by boosting private enterprise through greater foreign direct investment and divesting government-owned companies.

He has a job on his hands. More than two decades after India’s economic liberalisation, the government still operates in a range of public sector enterprises, from its well-known interests in atomic energy, petroleum, coal and air transport, to more baffling forays, such as the manufacture of salt, photographic film and even wristwatches.

At last count, PSUs were collectively pulling in about Rs 1.2 lakh crore in revenue, but the profit-making enterprises tend to be in resource extraction or heavy industries. In the same year, poorly-performing PSUs lost almost Rs 30,000 crore, about half of the education budget.

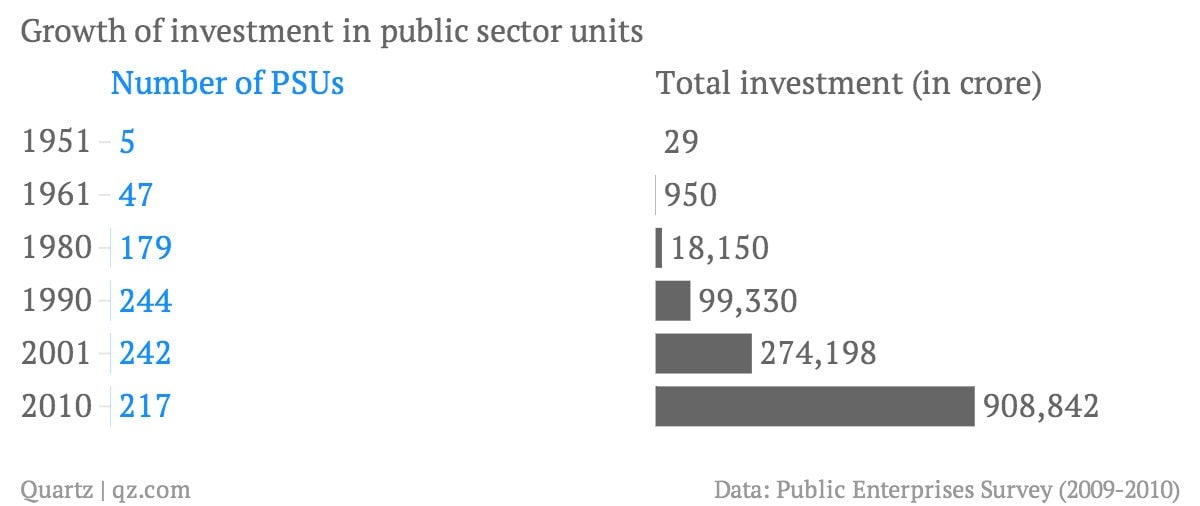

From the 1950s to the late 1980s, the number of public sector enterprises – and government investment in them – shot up by leaps and bounds. There were five active central government PSUs in 1951, receiving a total investment of Rs 29 crore. By 1990, there were 244 PSUs receiving more than Rs 99,000 crore as public investment.

After the economy was liberalised in 1991, there was a consensus in successive five-year plans that India did not need as many public sector enterprises as before. Before liberalisation, the government had a list of 17 industries that were considered the exclusive territory of the public sector.The list was pared down after 1991, and since 2001 only three industries have been reserved exclusively for the public sector: atomic energy, minerals specific to atomic energy and the railways.

Under the United Progressive Alliance government’s National Common Minimum Programme, it was also decided that while profit-making PSUs would not be privatised, those that were chronic loss-makers or were otherwise non-performing would be sold or closed after paying what employees were owed. Despite this, India continues to have a massive number of PSUs that demand huge investment and continue to lose a great deal of money.

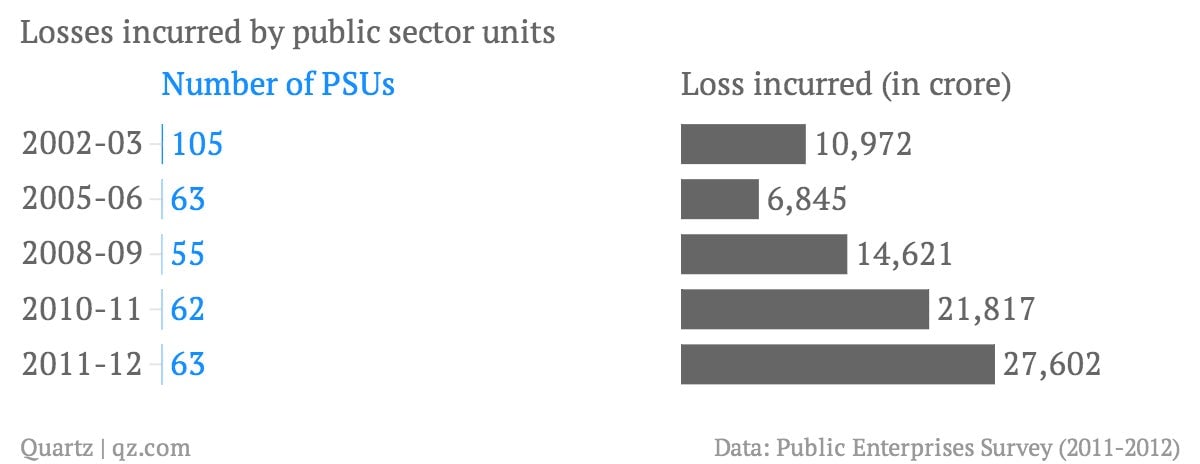

According to the government’s annual Public Enterprises Survey, there were 225 active PSUs under the central government in 2011-12, of which 63 incurred collective losses worth Rs 27,602 crore – 26% more losses than in 2010-11.

A decade ago, in 2002-03, there were a greater number of loss-making PSUs, but they incurred smaller total losses. Over time, even though the number of loss-making public companies has reduced, the amount of losses they incur has been clearly growing larger:

There are a significant number of profit-making PSUs as well – in 2011-12, there were 161, bringing in profits of Rs 1.2 lakh crore. But every year, the top profit-making public companies come from the industries dealing with oil, coal, steel and heavy electricals. The Oil and Natural Gas Corporation has consistently brought in the largest chunk of PSU profits – 20% in 2011-12 alone.The top loss-making public industries are the telecom companies Bharat Sanchar Nigam Ltd and Mahanagar Telephone Nigam Ltd, Air India, Hindustan Cables, Fertilizer Corporation of India and Shipping Corporation Ltd.

While there is certainly an argument to be made for the continuance of many of these companies, it seems strange that the state continues to involve itself in the running of airlines and hotels, and the manufacture of tyres, cement, textiles or scooters.

Here are some of the odd public-sector units that the central government still spends time and resources running:

Hindustan Salts Ltd (and its subsidiary Sambhar Salts): Headquartered in Jaipur since 1958, this is the only PSU engaged in the manufacture of salt. Most of the salt and rock salt it produces is sold to the textile, soap, detergent and leather industries.

HMT Watches Ltd: Set up in 1961 in Bangalore, HMT was the first manufacturer of wristwatches in the country. Its website claims the company drew inspiration from Nehru’s vision to “bring in a sense of time consciousness among the Indians”. The company has five manufacturing units and claims to have 100 million customers.

Hindustan Photo Films Manufacturing Company Limited: Based in Tamil Nadu, this company makes photographic and cine-films, x-ray films and photographic paper, among other things. In 2011-12, it was fourth on the Public Enterprise Survey’s list of India’s top ten loss-making PSUs.

Balmer Lawrie & Company: Based in West Bengal, Balmer Lawrie is a 147-year-old company started by two Scotsmen. Now a PSU under the ministry of petroleum and natural gas, it manufactures industrial packaging, greases, lubricants and performance chemicals. More interestingly, it also provides services in logistics and travel and tourism, including personalised, international tour planning through a brand called ‘Vacations Exotica’.

Hotel Corporation of India: This company came about when Air India decided to get into the hotel industry, and is now owned by the National Aviation Company of India. It runs the two Centaur Hotels in Delhi and Srinagar.

Cawnpore Woollen Mills Branch: A subsidiary of the British India Corporation, the company was established in Kanpur in 1876 – it’s age evident in its spelling of ‘Cawnpore’. It’s involved in the manufacture of pure wool materials.

Scooters India: A Lucknow-based manufacturer of three-wheelers, Scooters India makes a range of different autos that are used across the country, under the brand name ‘Vikram’.

Fresh and Healthy Enterprise Ltd: Headquartered in Haryana, this company, under the ministry of railways, is in the business of providing cold storage infrastructure for trade of fruits and vegetables.

This post originally appeared in Scroll.