India’s power crisis is set to worsen, unless the Modi government acts fast

The Supreme Court’s decision to cancel 214 of the 218 coal blocks, despite how drastic it seems, is unlikely to have any short-term impact.

The Supreme Court’s decision to cancel 214 of the 218 coal blocks, despite how drastic it seems, is unlikely to have any short-term impact.

But it could effectively derail India’s already beleaguered power sector in the longer term—unless the Narendra Modi government can ensure a smooth transfer of ownership of the cancelled coal assets.

Of the 214 blocks that the court cancelled on Wednesday citing irregularities in allocation, 42 blocks are in production. These will remain operational for a period of six months so that coal supplies aren’t suddenly impacted. The leases for the remaining 172 blocks have been cancelled immediately.

The six-month window means that “it doesn’t add to India’s power worries” immediately, said Kuljit Singh, partner, infrastructure practice at Ernst and Young.

Subsequently, much will depend on how the the government handles the transfer of ownership of the cancelled coal blocks. Some are likely to be auctioned to private firms, while others will remain with state-owned companies.

To work all this out, the government has just six months. ”It can either make a hash of it, or it can be successful,” said Ashok Khurana, director general of Association of Power Producers, which represents 29 private power developers.

Transfer of ownership can be a long drawn process that can take up to 12-15 months, according to Khurana, although a smooth transition will not disrupt coal supplies.

But if that doesn’t happen, the impact could be severe, as 70% of India’s electricity production is coal-powered.

And earlier this month, coal was running out at nearly half of India’s power plants because state-run Coal India just couldn’t keep up with the recent surge in electricity generation.

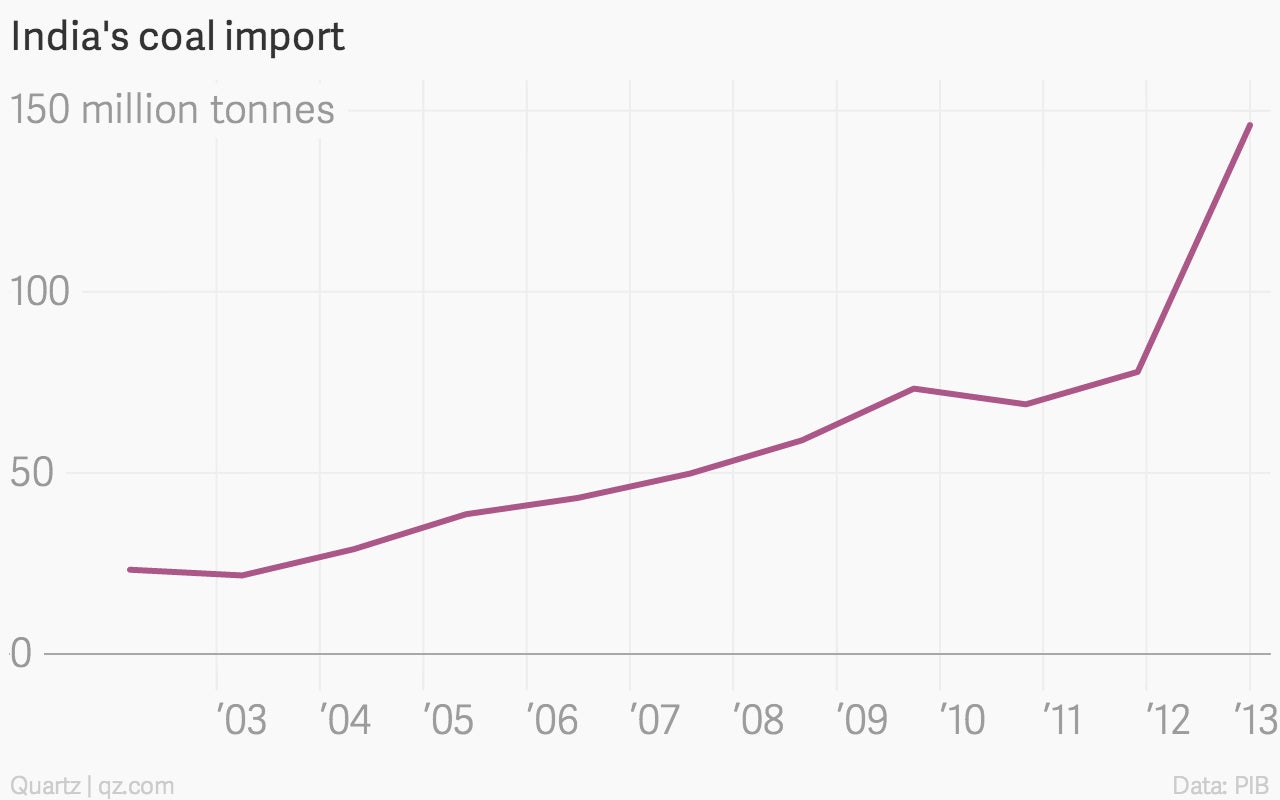

During 2013-14, India produced 571 million tonnes of coal, while its total consumption was of 739.42 million tonnes. As a result, coal imports spiked.

The Supreme Court ruling has also created uncertainty among companies operating in India’s power and infrastructure sector putting projects worth $47 billion in jeopardy.

“They would be worried about investing more money,” said Madan Sabnavis, chief economist at Care Ratings, a ratings agency.