IIT students may give the Indian Navy its next big thing: an intelligent unmanned submarine

In a country where schools and universities have long championed rote learning, a team of engineering students is doing pioneering work on “a submarine with a brain of its own.”

In a country where schools and universities have long championed rote learning, a team of engineering students is doing pioneering work on “a submarine with a brain of its own.”

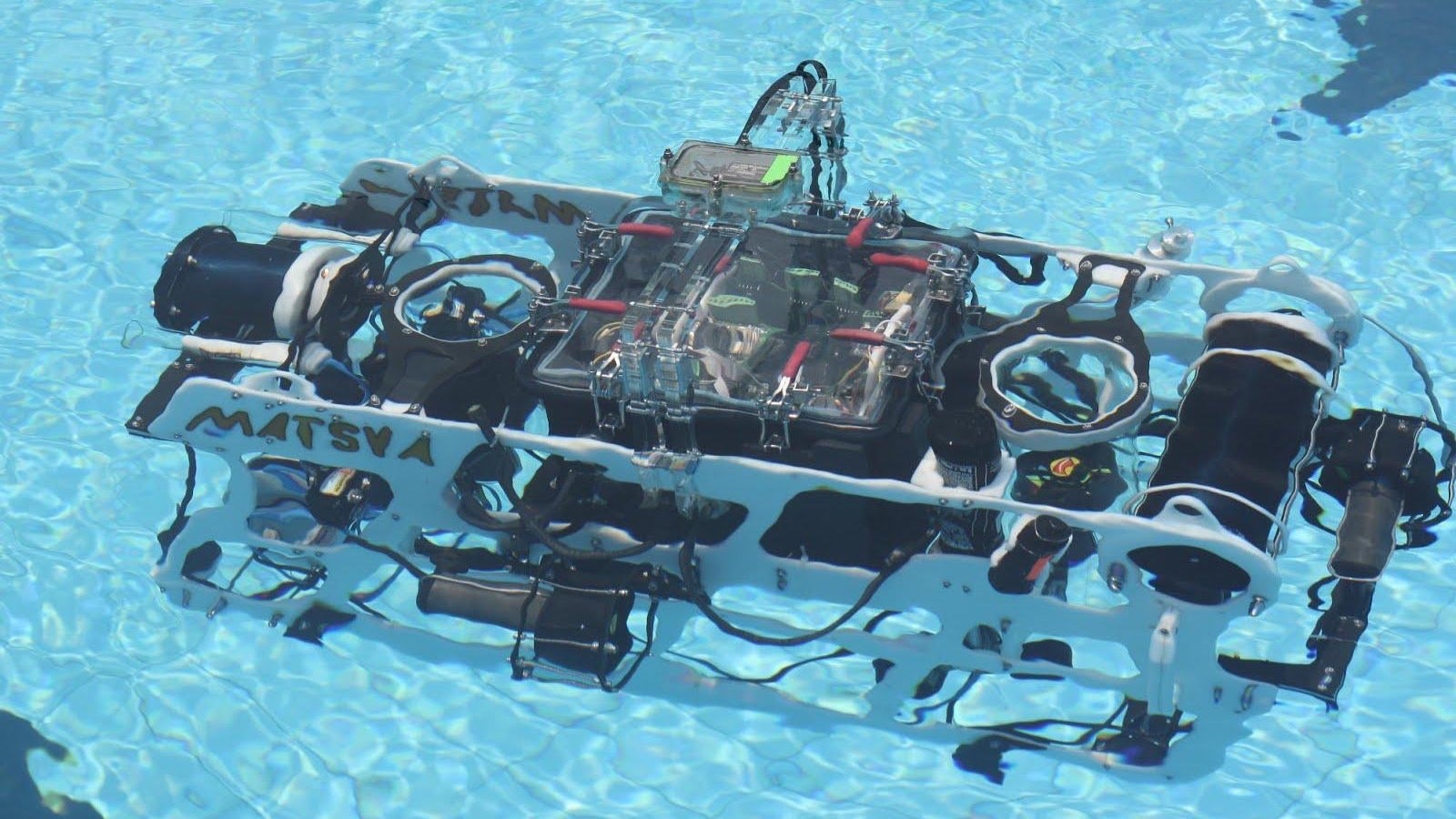

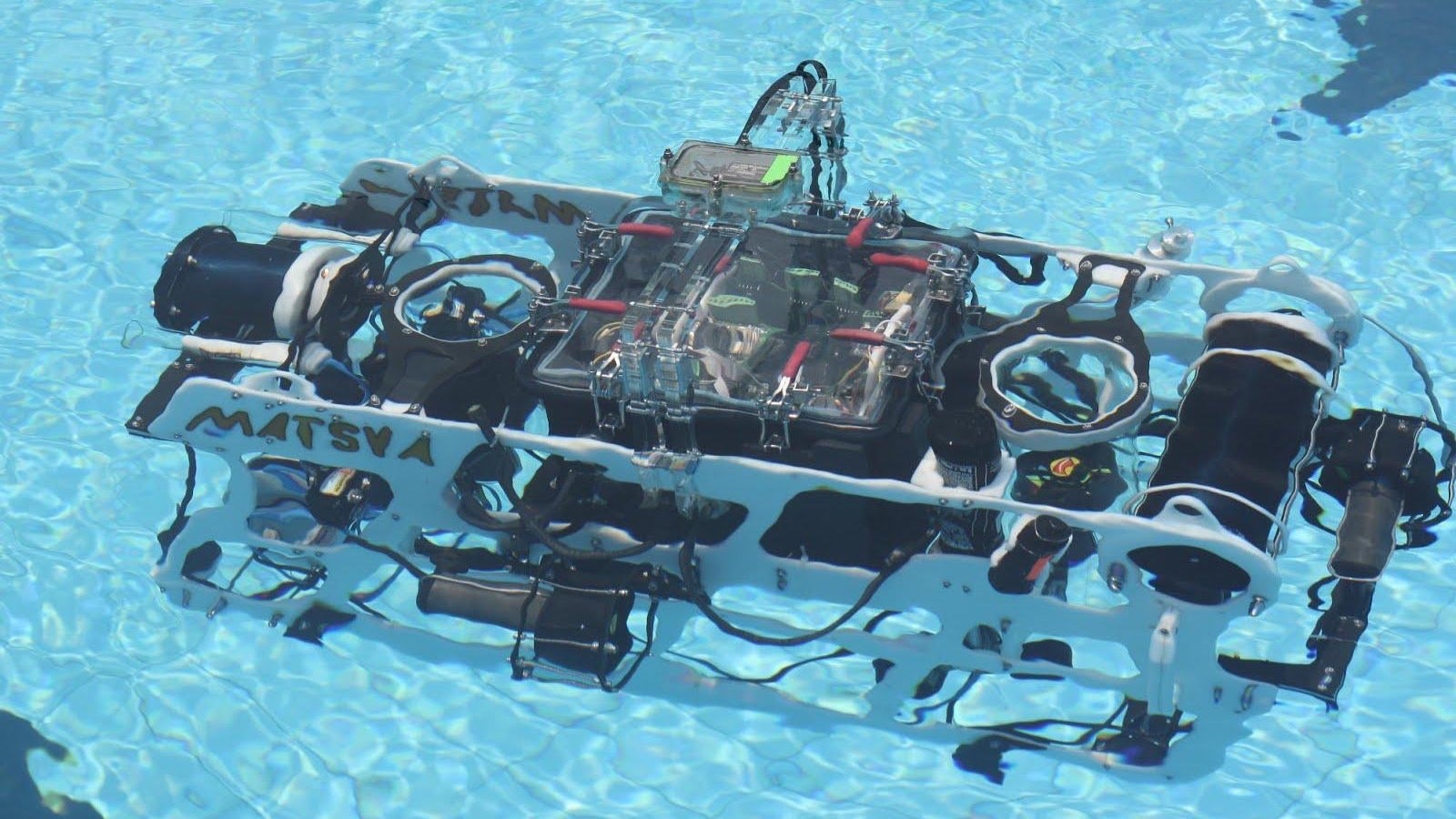

Since December 2011, students at the Indian Institute of Technology-Bombay have been working on Matsya, an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) that can control its own movements and execute specific tasks without human intervention.

The project, if successful, can change the future of defence in India by making underwater vehicles intelligent enough to understand their surroundings and react accordingly. For now, the unmanned vehicles used by the country’s naval forces are not exactly intelligent machines—they’re piloted remotely. This means they cannot venture into unknown waters and respond to unusual activity or even an enemy submarine by themselves. Matsya’s technology could train machines to act independently.

Military forces in the US and China already use unmanned submarines and the global AUV market is on track to more than double from $211.8 million in 2016 to $497.9 million in 2022, thanks mainly to defense demands. India’s foray into the field is fairly new, though. “While space exploration has been unmanned for obvious reasons, development of underwater unmanned vehicles started [in India] only recently,” the IIT project’s 21-year-old team leader, Varun Mittal, told Quartz.

Matsya, named after Hindu god Vishnu’s fish avatar, can ensure constant monitoring and immediate intelligent action during military operations, eliminating the room for human error. Using it, ecologists, too, can explore depths hitherto off limits for humans or monitor ocean life more consistently and accurately.

Even though Delhi Technological University, IIT-Madras, and other government entities worked on AUVs before 2011, the Matsya team is “aiming to make something no one in our country has achieved ever before.” Their autonomous submarine is intelligent enough to re-attempt a task if the previous try is unsuccessful.

Testing new waters

The AUV-IITB team comprises upto 30 undergraduate students from the mechanical, software, and electronics verticals, who spend late nights—9.30pm to 12.30am—every day after regular classes. On weekends, they work longer. “It’s a challenge to motivate people when doing something related to tech because it can take months or years of hardwork to get results,” Mittal said.

Matsya’s initial prototype operated on a simple “single-hull system” that could navigate from one point to another and identify objects underwater. Seven years in the making, its applications have extended to ”dropping markers, shooting torpedoes, grabbing objects, listening to underwater sound sources, [and] identifying different colours and shapes all on its own,” Mittal said.

Each year, the team recruits freshmen and seniors graduate. Despite the churn, their performance is unaffected: They have won the best Indian team title at RoboSub, an international AUV competition, for four consecutive years since 2012. During RoboSub 2016, when 50 teams from 11 countries faced off in San Diego, Matsya bagged the second place overall despite being penalised for exceeding the 38-kg limit. The top spot went to Caltech University by a slim margin, according to the breakdown of the scores. Last December, the team came out on top at the National Institute of Ocean Technology’s (NIOT) Student Autonomous Vehicle (SAVe) competition held in Chennai.

Next up, it is creating a more hydrodynamic fifth-generation prototype for the 20th edition of RoboSub this July. The competition is organized by the US Navy and the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI), the world’s largest nonprofit organization with an exclusive focus on advancing unmanned systems and the robotics community.

Swimming big

Currently, the 3.5-feet Matsya ventures upto 150 feet under water with batteries that last four hours. In comparison, Boeing’s AUV is over 30 feet long and dives as deep as 20,000 metres (6,096 feet).

Leena Vachhani, an associate professor in IIT-B’s systems and control engineering department who has been involved with project since it’s inception, describes Matsya as “a mini AUV” designed for shallow-water tasks like “cleaning of water tanks and lakes.” Once the IITians master its functionality, they hope to scale up their “micro-submarine” technology for real world applications.

“Each team leader comes up with his vision on his own,” Vachhani told Quartz. The team is in talks with the Indira Foundation to map River Ganga’s dolphin population using Matsya’s hydrophones, an underwater microphone that detects sound waves. The Indira Foundation is an association of IIT-B alumni, providing scholarships and funding student research.

IIT-B’s design could prove revolutionary for Indian military operations: autonomously shooting torpedos; placing and monitoring sensors on the seabed; tracking down and destroying enemy submarines by itself. AUVs could also carry out rescue missions, recover remnants from plane crash sites and locate black boxes, Mittal says, like the AUVs looking for the missing Malaysian Airlines plane.

Matsya can also conduct routine sub-sea inspections like checking for leaking underwater oil pipelines, while ecologists can use it to monitor flora and fauna and environmental conditions.

Funds crunch

The IIT students are strapped for funds, though. To build and showcase Matsya at competitions, AUV-IIT needs Rs2.5 million ($36,708) this year, of which more than half the amount goes towards purchasing sensors and cameras. So far, the team has gathered more than Rs1.5 million ($22,025) from the institute and other government sources and it’s still using up a one-time grant of over Rs2.5 million it received from the Naval Research Board (NRB) at the Defense Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) in 2013. But the team desperately needs more.

Unfortunately, private sponsors are reluctant to place their bets on a first-time experiment. “Especially in our country, technology is just starting to boom here,” says Mittal. “So people think a lot before investing.” The only way companies provide sponsorships is in the form of discounted parts for Matsya.

“If asked where do we stand now on a scale of one to 10, where one denotes only a prototype and 10 a product of industry level, I would say we are currently somewhere near six or seven,” said Mittal. Although there is no official launch date for Matsya’s defense or ecological deployment, he says an optimised, functioning version of their vehicle could be ready within four years.