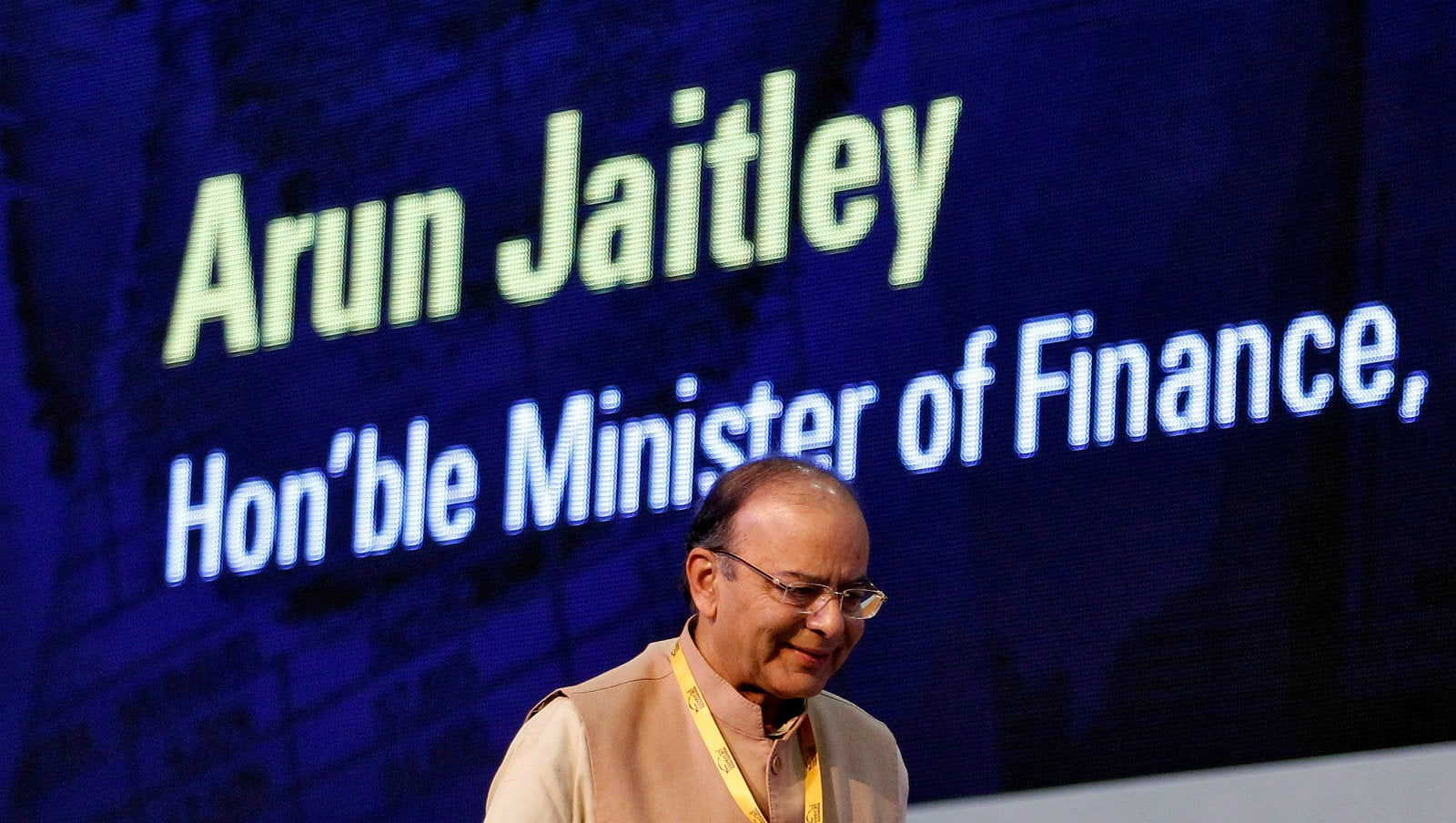

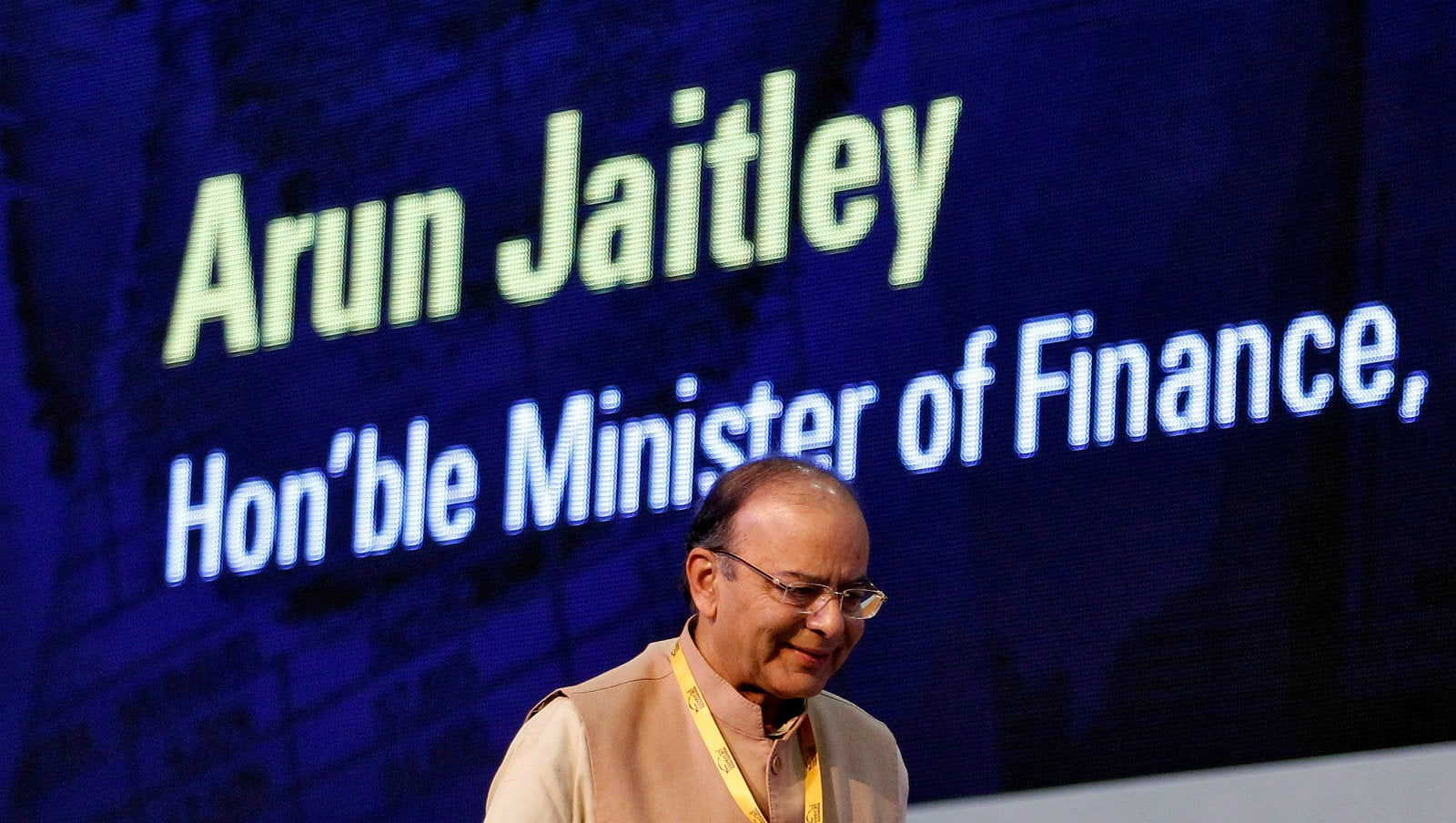

11 charts you need to see before Arun Jaitley presents India’s annual budget

On Feb. 01, Indian finance minister Arun Jaitley will rise in parliament to present the Narendra Modi government’s fourth budget.

On Feb. 01, Indian finance minister Arun Jaitley will rise in parliament to present the Narendra Modi government’s fourth budget.

Jaitley will have to execute an unenviable tightrope walk. On one hand, he’ll have to attempt resuscitating growth in Asia’s third-largest economy, still reeling from the impact of demonetisation, through higher public investment and more welfare spending. Alongside, he might have to add some tax giveaways to help ordinary Indians tide over the impact of pulling two of India’s highest denomination notes out of circulation last November.

There is also some politics to consider: This will likely be the Modi government’s last opportunity to present a non-populist budget before it pulls out all the sops in the run-up to the 2019 polls. However, with five states, including Uttar Pradesh and Punjab, going to the polls through February and March, voters will be keenly watching out for possible goodies from Jaitley.

At the same time, the finance minister will have to ensure that India’s fiscal deficit—the excess of total expenditure over receipts—is under control. Although it has been on a steady downward trajectory for some time now, he will find it increasingly difficult to rein it in under 3% of the GDP in the coming financial year, if he decides to spend big.

Rating agencies, which the Modi government has for some time been unsuccessfully angling for an upgrade, are watching closely. Standard & Poor’s, for instance, has said that continuing fiscal consolidation will be crucial for any improvement in India’s ratings, currently at “BBB-minus,” just a step above junk status.

Jaitley’s budget will also give out the current account deficit (CAD) numbers for the year. The CAD—the amount by which the value of imports exceeds that of exports—had been a problem prior to 2014. But a steady fall in oil prices (India imports almost 80% of its fuel requirement) has helped bring down the CAD in recent years. Crude oil and petroleum products constitute around 36% of India’s total imports.

Show me the money

So where’s Jaitley going to get the money from?

The finance minister seems confident that demonetisation—in spite of the economic chaos it created—will trigger an increase in tax revenue fairly quickly, giving the Modi government some additional spending firepower. Alongside, the much-delayed good and services tax (GST) may finally come into force during next fiscal, helping the government bring in more revenue.

However, there are uncertainties. For one, the number of Indians who might be brought into the tax net as a result of demonetisation is unclear, as is the quantum of tax evasion that will be curtailed. Only 12.5 million Indians paid taxes in the 2013 financial year, according to data released last year. Simultaneously, there is no assurance that the GST will see the light of day in July 2017, given that it’s been stuck in the pipeline for 16 years.

The finance minister’s other option is to borrow.

But that’s easier said than done. The total outstanding debt of the central government is already pretty high at 67% of the GDP, which has been flagged as a concern not only by rating agencies but also the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). India’s debt-to-GDP ratio is higher than that of most other Asian economies.

If Jaitley decides to spend big on subsidies and the social sector, then the government will have to make provisions. A greater reliance on borrowings will not bode well for India’s already high debt-to-GDP ratio, as that means the interest cost, a substantial part of the government’s expenses, shoots up.

Here’s how much the government has borrowed every year since 2010:

Getting India Inc. going

Alongside balancing the fiscal math, Jaitley will have to attempt kickstarting India’s economic engine through a mix of incentives, tax sops and new policies, as well as by revisiting some old initiatives. Already GDP growth estimates have been lowered primarily due to the currency ban. The World Bank, for instance, has revised its 2017 fiscal year GDP growth estimate for India to 7% post demonetisation, from its earlier 7.6% projection.

The index of industrial production (IIP), an indicator of growth in sectors like mining, manufacturing, and electricity, has seen negative growth for most of the last one year.

India’s bank credit growth, too, mirrors this weak growth. The figures for the growth in loans extended to individuals and businesses have been rather flat, indicating that companies aren’t exactly borrowing enough for expansion and operations. Here, too, demonetisation has caused serious disruption. For the fortnight ended Dec. 23, more than six weeks after the currency ban, bank credit growth plunged to 5.1%, the lowest in decades.

In particular, demonetisation hasn’t helped manufacturing. Early indicators suggest that the sector has been hit hard as the cash crunch has delayed new orders, payment of wages, and raw material procurement.

The proportion of manufacturing in gross value added (GVA), the value of all goods and services produced in the economy, has been falling.

Additionally, fresh data from the Labour Bureau shows that the manufacturing and construction sectors have seen the highest number of job losses in the July-September 2016 quarter (employment data typically comes with a lag).

Clearly, Modi’s flagship programmes like Make in India haven’t worked either. The initiative aims to revive manufacturing and increase its share to 25% of the GDP by 2020. So, all eyes will be on Jaitley’s ability to support the sector with incentives and investment.

Meanwhile, there’s another number he will keep an eye on: inflation. For years, India has battled high inflation. But with prices under control, the challenge before the finance minister would be to boost growth without flaring up inflation. Given that the figure is benign now, India’s central bank will be able to support him by slashing interest rates so that borrowing costs for businesses is lowered.

(Extra)ordinary spending

Not just industry, the budget will have to factor in support for the ordinary Indian, too.

Expenditure on the social sector, including key areas like education and health, has fallen since the Modi government came to power in 2014. However, in the aftermath of demonetisation, there may be a more proactive effort to bolster the sector, as suggested by the prime minister’s speech on Dec. 31.

Jaitley will also be watching India’s subsidy spending which has ballooned from Rs1.2 lakh crore in 2010 to Rs2.5 lakh crore in 2016. The good news is that following the deregulation of petrol and diesel prices (in 2010 and 2014, respectively), the bill on petroleum products has steadily declined, while those for other major heads have stayed steady.

And if all that wasn’t enough, Jaitley’s budget speech must outline the plan for Indian Railways—for the first time in 92 years, there will be no separate railway budget.

The numbers show that things have been looking up for the transporter lately, with railway minister Suresh Prabhu presenting an ambitious blueprint in last year’s (final) rail budget.

But there have been concerns over procuring funds to push the railway’s infrastructure agenda. Indian Railways has a very high operating ratio (around 94% in the current fiscal), which means most of its revenue is spent on meeting expenses, leaving little for investment.

Under Prabhu, it is trying to improve freight earnings, its main revenue source, and building up “non-fare revenue” like making more space to advertise on railway properties, to installing ATMs, and reportedly even allowing wedding receptions on railway platforms.

On Feb. 01, can Jaitley get the party started?