India doesn’t know what to do with all its young people

As the world’s fastest-growing major economy, India would seem to be a place with plenty of jobs, especially for its youth. But the reality is very different.

As the world’s fastest-growing major economy, India would seem to be a place with plenty of jobs, especially for its youth. But the reality is very different.

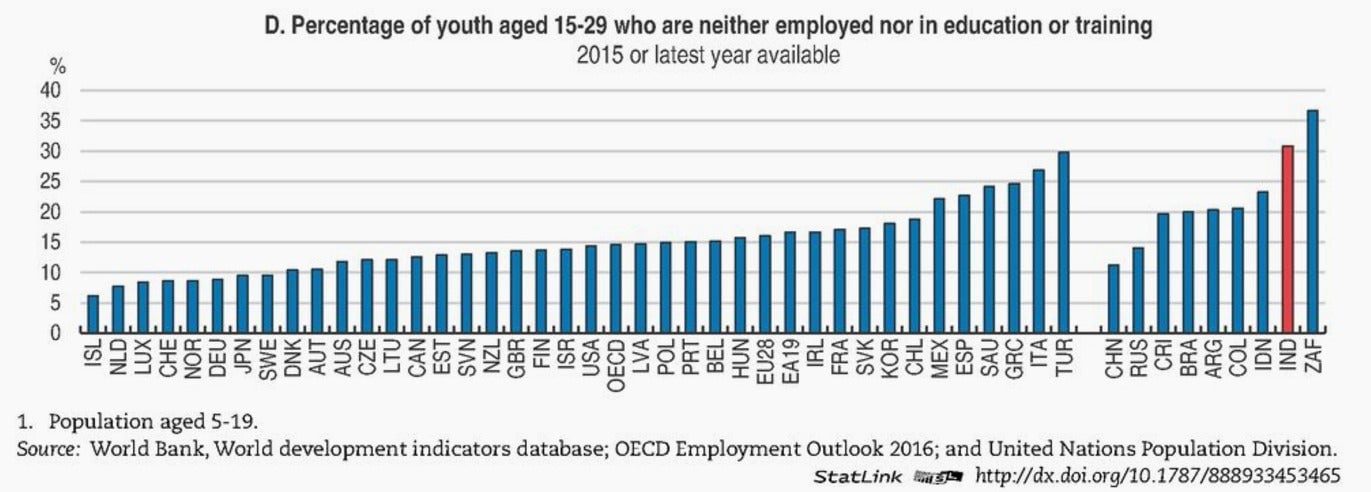

Over 30% of Indians aged between 15 and 29 aren’t employed or part of any formal education or training system, far more than in China, Brazil and Russia, according to a report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The only country with a higher rate of youth not engaged in employment, training or education (NEET) is South Africa, the OECD’s Economic Survey of India, 2017, said.

And that’s a cause for concern because Asia’s third-largest economy is expected to have the largest youth population in the world by 2020.

Young Indians often struggle to find permanent jobs in the organised sector of the economy as companies try to avoid labour-intensive strategies to gain tax incentives, Isabelle Joumard, a senior economist and head of the India desk at the OECD, explained to the Mint newspaper.

“…. Corporates in India tend to rely more on temporary contract labour, stay small or substitute labour for capital to avoid strict labour laws. Apart from that, corporate income tax has created a giant bias against labour-intensive activities,” Joumard said.

In addition, India’s economy is also going through a phase of expansion without jobs, partly the result of poor growth in the country’s manufacturing sector which is dragging down industrial activity.

“Job creation has not kept pace with GDP growth,” Madan Sabnavis, chief economist at CARE Ratings, wrote in April 2016. And in 2015, only around 135,000 jobs were created in India, the lowest amount in seven years, president Pranab Mukherjee said in November last year.

What’s more, the jobs that are available aren’t high quality either.

“India creates too few quality jobs to meet the aspiration of the growing workforce, leaving many people under-employed, poorly paid, or outside the labour force,” the OECD said in its report.

While the Narendra Modi-government is trying to improve the employability of the youth with its Skill India program, some initial results show that those under the initiative aren’t finding many jobs either. And the country’s low literacy rate and poor spending on public education aren’t helping. The dismal education system, with teacher absenteeism and limited learning outcomes, forces many students to drop out of schools, leaving them largely unqualified for future employment.

As a result, many young Indians find themselves working in the country’s massive unorganised sector, stuck with temporary jobs, daily wages, and none of the benefits that a formal job would entail.