A century of Indian-American radicalism explodes the myth of the docile “model minority”

Barnali Ghosh and her husband, Anirvan Chatterjee, were sick and tired of the “model minority” myth about South Asians in the US being high-achieving and politically docile.

Barnali Ghosh and her husband, Anirvan Chatterjee, were sick and tired of the “model minority” myth about South Asians in the US being high-achieving and politically docile.

“I would often come across this perception that activism was not something that South Asians do—not something you talk about with your family, or your parents encourage you to take on,” Ghosh, 42, told Quartz. “We wanted to change this narrative. To put forward that activism and organizing and fighting for justice was something that was as much part of our tradition as Bharatnatyam or Bollywood.”

That’s why the two created the Berkeley South Asian Radical History Walking Tour, in Berkeley, California, as an antidote to this misperception, inside and outside the community.

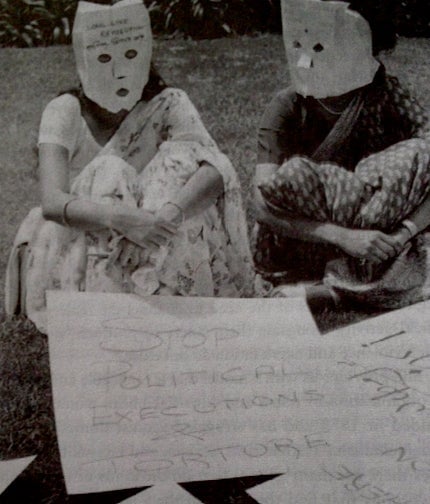

On the three-hour tour, the couple tells stories of South Asian political action on the sites where it happened: Punjabi freedom fighters that organized immigrants in California in the 1910s; university students who protested prime minister Indira Gandhi’s civil rights abuses in the 1970s; the creation of perhaps the oldest South Asian LGBT magazine in the US in 1980s; Berkeley High School students fighting xenophobia after 9/11 terrorist attacks in the 2000s.

“When do you think the first recorded South Asian protest happened in Berkeley?” asked Ghosh, 42, leading the tour recently along with Chatterjee, 39.

A number of people on the tour threw out guesses. Though we had already spent an hour learning about the long history of South Asian political action locally, none of our guesses went back far enough.

The correct answer is January 18, 1908, Ghosh explained, informing us that we are standing almost exactly where it happened. On that day, 16 South Asian students at the University of California-Berkeley gathered to protest the racist ideas of a Christian evangelist who was speaking at the school.

Ghosh and Chatterjee met in Berkeley almost a century later, in 2002. Appropriately, they were attending a showing of Muktir Gaan, a documentary about the role of music in the Bangladeshi freedom struggle. Ghosh, born in Bangalore, India, had moved to Berkeley two years earlier to study landscape architecture. Chatterjee, who grew up in the Bay Area, had also moved to Berkeley for graduate school, but dropped out and started a small tech company.

They became politicized after 9/11, horrified by the way Middle Eastern and South Asian people were treated after the attack. In the course of participating in anti-Iraq war protests, Chatterjee describes repeatedly meeting South Asian activists whose experiences enthralled him. “These people don’t necessarily think of their stories as all that exciting, but I was blown away,” said Chatterjee.

In 2012, after years of exploring the South Asian history of Berkeley, the two finally decided they needed a vehicle to relay all they had found. “We were mapping it out in our heads how all this stuff happened in Berkeley at different times,” said Chatterjee. “It became so obvious that you could visit all these different sites on a walking tour.”

The emotional core of the tour is an account of the life of the political martyr Kartar Singh Sarabha. The story is narrated by Ghosh and acted out by Chatterjee. (Both have theater backgrounds.)

Kartar, a Punjabi Sikh born in British-occupied India, arrived in San Francisco in 1912 as a 17-year-old to study electrical engineering at Berkeley. Though he came from a wealthy family, and there were no laws against Indians immigrating to the US, he was detained for three days on suspicion that he was likely to become dependent on the government.

Appalled at the racist treatment he experienced, and inspired by the South Asian activists already in Berkeley, Kartar became involved in the Indian independence movement. As a member of the Ghadar Party, the popular name for Hindi Association of the Pacific Coast, Kartar organized South Asian laborers and farmers living in California to support the freedom cause. Kartar returned to India in 1919, and participated in planning armed revolt against the British. The British found out about the revolt before it happened, and Kartar was executed.

Ghosh and Chatterjee became visibly emotional as they told Kartar’s story, and many of the tour-goers were on the verge of tears. That’s part of the point, says Ghosh: “The tour is intended to reach people in their hearts and not just their minds,” she explained. “For most of us our experience of learning history is one where its a bunch of facts, dates, and names. It doesn’t really make you understand context or why it should matter to you.”

The last story of the tour is one of the couple’s favorites. On the steps of Berkeley High School, Chatterjee explains that following 9/11 there were a rash of xenophobic acts against Middle Eastern and South Asian residents. Parents of Middle Eastern and South Asian students were afraid of their kids attending school. In response, the South Asian student group Cultural Unity—largely made up of low-income immigrants—organized workshops and an assembly to educate other students about Islam, South Asia, and the Middle East. The students also started a safety committee to walk South Asian and Middle Eastern students to school, if they felt uncomfortable alone. The organizing culminated in the Berkeley City Council passing a bill to make the city a “Hate-Free Zone.”

Fundamentally, Ghosh says, the Radical Walking Tour is about helping South Asians in the US rethink their history. She worries that South Asians, one of the wealthier ethnic groups in the US, are too often “on the sidelines” during civil rights debates. If they better understood the history of oppression, suspicion, and exclusion their own people faced in this country, they might feel the need to act, she reasons.

“It was life-changing for me when I realized that the 1965 Immigration Act, that opened the United States to South Asians, was a result of the civil rights movement,” says Ghosh. South Asians had been effectively barred from immigration since 1917. “[South Asian Americans] owe a debt to African American civil rights activists for fighting for racial inequality. So today, we should want to stand in solidarity with people of color.”