It’ll take more than an exchange rate change to get Lebanon out of its deep crisis

The change is part of a set of conditions the IMF imposed on the country to qualify for financial aid

Lebanon’s currency has been pegged to the US dollar at the rate of 1,507.5 Lebanese pound (LBP) per dollar since 1997. The finance ministry was due to revise the official exchange rate to 15,000 LBP tomorrow (Nov. 1).

The change represents one of the conditions the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has laid out for the country to get $3 billion in financial aid, and a bid to unify the country’s multiple, unofficial—but widely-used—open market exchange rates.

Some, however, fear the move could do more harm than good to a currency that’s devalued rapidly in the last three years, especially coming at a time of political uncertainty as president Michael Auon just resigned, largely symbolically, one day ahead the end of his term, with no successor on the horizon.

“This will be terrible for people. Everything is going to cost more,” Lina Boubess, a 62-year-old activist who has been labeled “Mother of the Revolution” for being a constant presence at the protests since country’s economic turmoil began in 2019, told DW last month.

Brief history of Lebanon’s economic collapse

In the aftermath of its 1975-90 civil war, Lebanon racked up insurmountable public debt to rebuild, except a bulk of those funds never actually contributed to public services, but simply kept a powerful elite comfortable while driving income inequality. As a recent World Bank analysis titled “Lebanon Public Finance Report: Ponzi Finance?” noted, the fixed exchange rate played a role in creating an illusion of wealth.

But the illusion of stability shattered in 2019, when the persistent underfunding of public services led the government to attempt to raise taxes on tobacco, petrol, and even Whatsapp calls, rather than targeting the wealthier segments of the population. The subsequent protests sparked capital flight from the country’s richest while other sources of foreign income, such as tourism, dried up leaving the massive debt in public finances completely exposed. Then prime minister Saad Hariri even resigned to, in his words, “make a great shock to fix the crisis.”

Since then, Lebanon has struggled to import food and fuel, a situation compounded by the covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine, while banks have imposed limits on the amount of funds their customers can access, leading some depositors in desperate need of liquidity to take matters in their own hands and rob the banks to access their own funds. Three-quarters of the population are estimated to have plunged into poverty. Despite various attempts to prop up the value of the currency, the Lebanese pound has plummeted in the black market as the country has been roiled by the liquidity crisis.

Lebanon’s crisis, in the words of the IMF’s mission chief

“The Lebanese economy remains severely depressed against continued deadlock over much needed economic reforms and high uncertainty. GDP has contracted by over 40 percent since 2018, inflation remains in triple digits, FX reserves are declining, and the parallel exchange rate has reached 38,000 LBP per USD. Amidst collapsing revenues and drastically suppressed spending, public sector institutions are failing, and basic services to the population have been drastically cut. Unemployment and poverty are at historically high rates.” —Ernesto Ramirez Rigo, after his September 2022 visit.

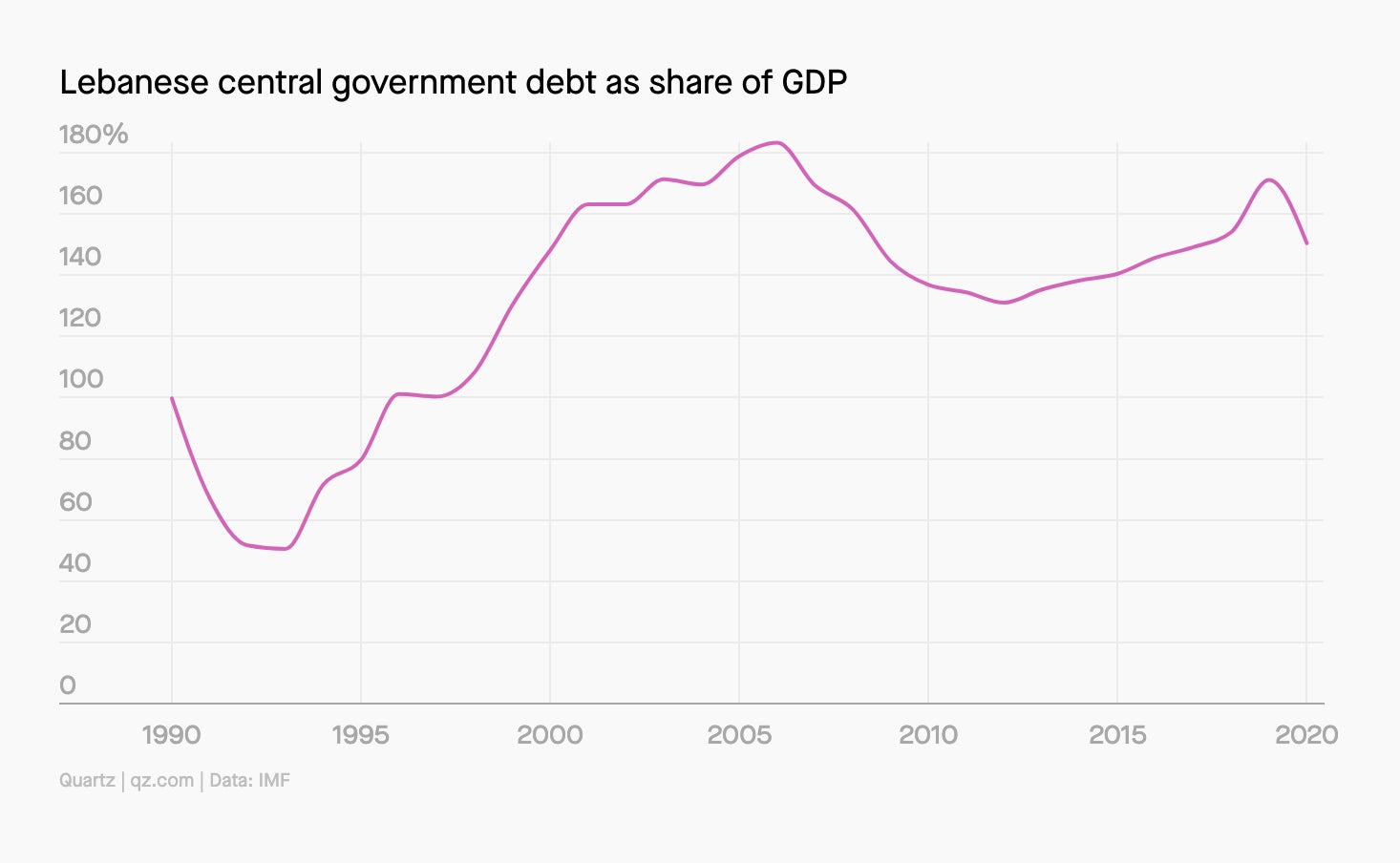

Charted: Lebanon’s debt

Other IMF conditions target the banking sector

For years, local private banks have been loaning to Lebanon’s central bank at extremely high interest rates. The top private banks control almost all of the banking sector’s assets and, for 18 out of the 20 top banks, their main shareholders either belong to the current political ruling class or they’re part of their inner circle. Prior to the collapse of the economy, the banks were convincing customers to swap out their greenback savings for local currency with high interest rates on the latter.

The banks have been at the center of public outrage because of levying withdrawal ceilings, restricting the flow of customers’ money, and shutting for prolonged periods. So, alongside changes to the currency exchange rate and approval of the 2022 budget, the IMF demanded several reforms in the sector.

For one, the government has to approve a bank restructuring strategy that “recognizes and addresses upfront the large losses in the sector, while protecting small depositors and limiting recourse to public resources.”

Secondly, the country has to reform its banking secrecy law to “bring it in line with international standards to fight corruption and remove impediments to effective banking sector restructuring and supervision, tax administration, as well as detection and investigation of financial crimes, and asset recovery.” Enacted in 1956, the banking secrecy law prohibits the disclosure of any information regarding any Lebanese banks’ clients, barring rare circumstances like bankruptcy filings, lawsuits between the bank and the client, or money laundering investigations. But experts believe it’s been getting in the way of transparency.

The Lebanese finance ministry has clarified that the new exchange rate implementation is contingent on the approval of a long-delayed financial recovery plan, Bloomberg reported.

Lebanon’s economic crisis, by the digits

82%: Lebanon’s multidimensional poverty rate in 2021, versus 42% in 2019, according to the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (UNESCWA)

36,600: Lebanese lira to buy one US dollar on Oct. 31 in the parallel market

95%: value the Lebanese lira has lost in the last three years

10-fold: how much food prices have increased since 2019

10 times: increase in cost of imports when the 2022 budget priced them at the new exchange rate

200%: inflation in Lebanon

80%: Share of Lebanon’s grain imports relying on Ukraine. Russia’s war in Ukraine has sent prices skyrocketing

1 million: Syrian refugees among the population that plunged into poverty

70: inspectors available to surveil businesses to prevent illicit price hikes and hoarding

$90 billion: public debt Lebanon defaulted on in March 2020; 170% of its GDP—one of the highest in the world

Exception to the exchange rate

As to not hurt banks further, Lebanese prime minister Najib Mikati has said the gradual rollout of the new currency exchange rate will exempt two categories:

🏦 Banks’ balance sheets

🏘️ Housing loan repayments

But with no way to protect customers’ frozen bank accounts, rising incidents of bank holdups may not let up.

Wait, what happens to the Lebanese government now?

Since gaining independence from France in 1943, the Lebanese government has followed a non-written “gentleman’s agreement” that suggests the president must be a Maronite Christian, the prime minister a Sunni Muslim and the speaker of the parliament a Shia Muslim. With Aoun’s term ending today (Oct. 31), the parliament should’ve found a replacement—but it failed to reach a consensus four times, and is now at a political stalemate.

In the event of a presidential vacuum, the Lebanese government fills in. Only the cabinet operating in caretaker capacity mostly won’t be able to govern strongly and implement economic reforms swiftly. The constitutional crisis piled on top of the economic one is not promising.

“The prospects of an IMF deal were already dim before the upcoming power vacuum and departure of Aoun,” said Nasser Saidi, an economist and former Minister of Economy. “There is no political will or appetite for undertaking reforms.”

Related stories

⚖️ Lebanon’s extreme income inequality is fueling its huge protests