The first African country to reach a FIFA World Cup semifinal is going head-to-head against its former colonizer

While France is heavily favored to win, the Moroccan team has managed to defy the odds

After Morocco won its quarter-final match against Portugal at the first world cup hosted by an Arab country, players and supporters could be seen waving a variety of flags: Morocco’s green star-studded red banner, Qatar’s maroon and white Al-Adaam, and Palestine’s triangle-adorned tricolor.

For a game entrenched in national identities and rich with symbolism, this striking scene showed how Morocco’s unlikely run as the first African nation to reach the World Cup semifinals has reverberated outside of the country’s borders, and echoed across the Arab world and beyond.

Now, the stage is set for Morocco to face France, the country that occupied Morocco for almost five decades, and exerted influence for 50 years more, in what will be the most important soccer match in the country’s history. The match won’t just be closely watched in Morocco, but also anywhere in the world, particularly Europe, where people of Moroccan descent see an opportunity to proudly celebrate their roots—as well as by anyone who loves an underdog.

The “milkshake” Moroccan diaspora

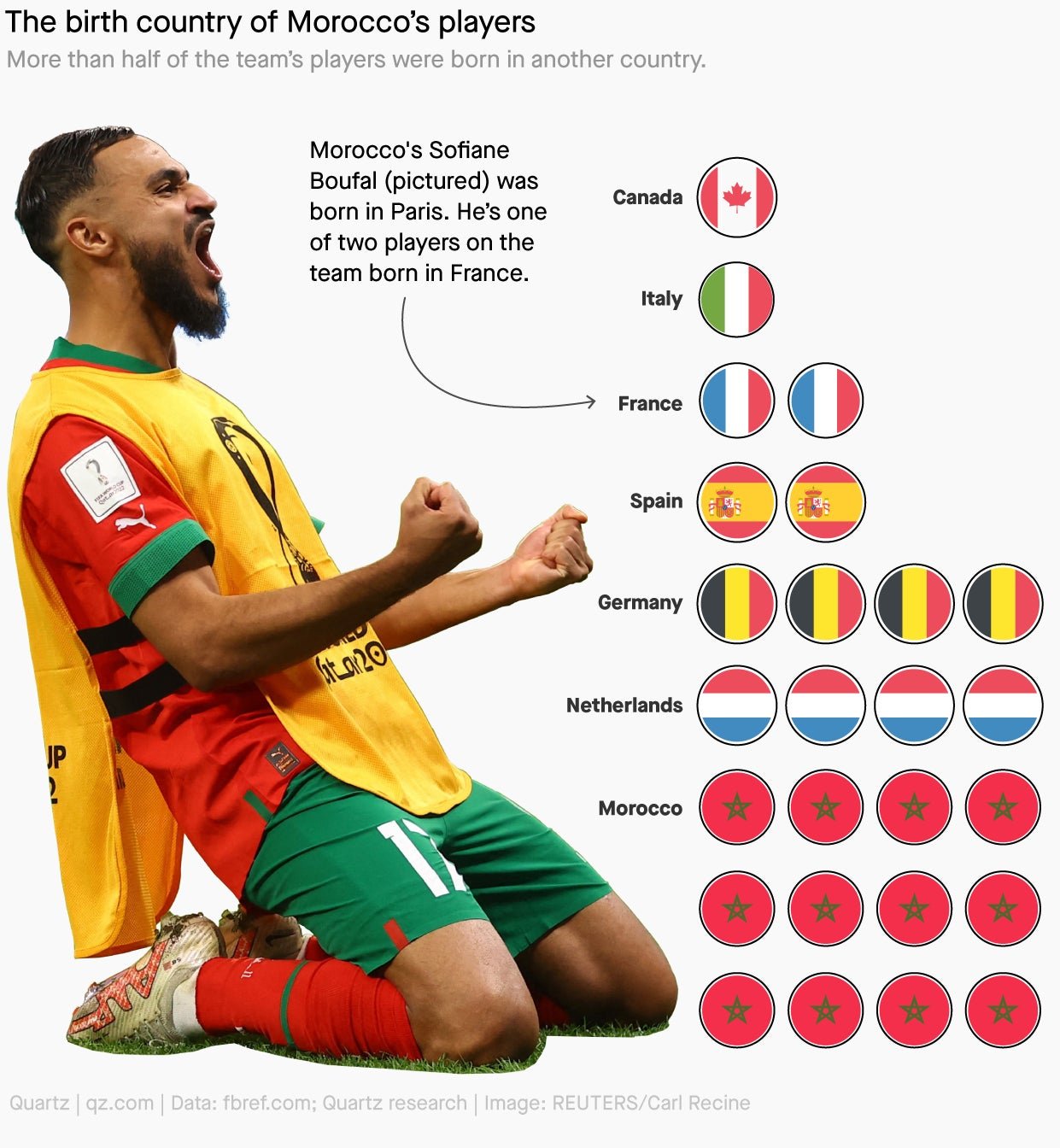

Even before Morocco played its first match, the team distinguished itself for the composition of its roster. Half of Morocco’s players in the 2022 World Cup were born in European countries to Moroccan parents, including Achraf Hakimi, the country’s star player who was born in Madrid.

This trend is not new. In the last World Cup, 17 of Morocco’s 23 players were born abroad. This circumstance is indicative of a Moroccan diaspora fueled both by the European colonization of North Africa and post-World War II policies in several European countries encouraging migration at a time of labor shortages. In total, an estimated five million Moroccans live abroad, with the largest expat community located in France.

Morocco’s coach Walid Regragui, who was born in Paris, pointed to the varied backgrounds of his players as a key part of the team’s success. He compared the formation of his squad to blending a milkshake, explaining that combining players who grew up in countries with diverse styles of play has made the team more creative.

That was the case for Morocco’s right-back Hakimi, a Paris Saint-Germain teammate of French phenom Kylian Mbappé in the French Ligue 1, who chose to wear the green-and-red uniform over Spain’s red-and-yellow jersey, even after living in Europe his entire life.

“I saw that [Spain] wasn’t the right place for me, I did not feel at home,” Hakimi told the Spanish publication Marca. “It’s what I felt because it was not what I had at home, which was Arab culture, being Moroccan. I wanted to be there.”

Brief timeline of Morocco’s European colonization

1860-1884: Spain declares war on Morocco, establishes settlements in the northern coastal region.

1904-1906: France first invades Moroccan ports and begins to collect tax. The Algeciras Conference in Spain formalizes European recognition of French authority in the region.

1912: Morocco becomes a French Protectorate after the Treaty of Fes, while Spain remains in control of two regions in the North.

1921-1926: A Berber independence movement is able to establish a republic in the Rif mountains, before being defeated by a coalition of Spanish and French forces in 1926.

1943: The Istiqlal party is founded to pursue Moroccan independence, partly funded by the US, and begin to actively subvert French rule.

1953: In an attempt to consolidate power, the French exile Sultan Mohammed V to Madagascar. The move causes widespread unrest and the French allow Mohammed V to return in 1955, paving the way for independence.

1956: Morocco officially declares Independence as France cedes its protectorate. Spain gives up part of its territory while maintaining control of two cities in the North, of which Morocco still disputes control.

Africa, the Arab world, and beyond…

Fervent support for Morocco goes beyond Africa and the Arab world. After Morocco beat Spain to qualify to the quarter-final stage of the tournament, Arab-American law professor Khaled Beydoun tweeted that it was a victory for Muslim immigrants around the world.

“As an Arab or Muslim, subaltern and marginalized person walking in a western world where your very identity spells ‘other’ or ‘lesser,’ yesterday’s Morocco victory was a revolutionary rebuttal,” Beydoun wrote.

Joyous reactions to Morocco’s underdog victories over Belgium, Portugal, and Spain were plain to see, with huge celebrations reported in immigrant communities across Europe which, in some instances, resulted in episodes of vandalism.

Some right-wing politicians, like former French presidential candidate Eric Zemmour, aimed to score political capital on post-game reports of rioting and clashes with police, suggesting it showed a lack of French identity among Arab immigrants. This rhetoric risks further inflaming divisions within European societies, while also depriving national soccer teams like Spain, France, (or Italy, which didn’t qualify for this year’s World Cup) of talented players who grew up in those countries, but who, like Hakimi explained, don’t feel at home there.

In Wednesday’s (Dec. 14) game, expect a blitzing French offense to challenge Morocco’s tight defense, anchored by Canada-born star goalkeeper Yassine Bounou, who has only conceded one goal (an own goal) so far this tournament. While France is heavily favored in the match, the Moroccan team has managed to defy the odds from the very start of the tournament. Win or lose, Morocco has already made history.