The New Yorker has cracked the code for literary virality with its short story, “Cat Person”

This post contains spoilers to Kristen Roupenian’s “Cat Person.”

This post contains spoilers to Kristen Roupenian’s “Cat Person.”

The top story today on newyorker.com isn’t a deeply researched investigation on corrupt men, or 6,000 words on an inevitable natural disaster. It’s a piece of fiction that reads like a friend, colleague, or sister telling you an anecdote about bad sex in college.

“Cat Person,” by Kristen Roupenian, is a short story in the December 11 issue of the magazine, published online Dec. 4. The story is about Margot, a college sophomore who, we can glean, is reasonably attractive, and Robert, an older man with whom she has text-based frisson, and, it turns out, not much physical chemistry. The series of thoughts and events Margot goes through in her brief, mostly digital, fling with Robert, is so commonplace, such a nonevent, that in real life it would be hardly worth mentioning. Yet in the voice of the narrator, Roupenian and the New Yorker have struck internet gold.

At time of writing, “Cat Person” is the most popular story on the New Yorker’s site. An interview with Roupenian is second. A New Yorker tweet of the story has 3,600 likes at time of writing, compared to 250 likes on the tweet announcing new fiction from Zadie Smith in March. A twitter account that just posts screenshots of men reacting to the story has 4,200 followers.

Many of the women reacting on social media seem to relate, however uncomfortably, to Roupenian’s Margot. She’s naive, insecure, occasionally aware of her sexual power, occasionally cruel, and inexperienced with knowing and saying what she wants. She’s overly emotionally accommodating to a man she’s just met, and constantly apologizes internally, blaming herself for perceived slights from Robert. At the climax of the story, she is turned off when she finally sees Robert undressed, doesn’t see a non-awkward way out, and has sex with him anyway–fantasizing about how she’ll look back on this moment with a future boyfriend and laugh.

A typical passage reads:

Margot laughed along with the jokes [Robert] was making at the expense of this imaginary film-snob version of her, though nothing he said seemed quite fair, since she was the one who’d actually suggested that they see the movie at the Quality 16. Although now, she realized, maybe that had hurt Robert’s feelings, too. She’d thought it was clear that she just didn’t want to go on a date where she worked, but maybe he’d taken it more personally than that; maybe he’d suspected that she was ashamed to be seen with him. She was starting to think that she understood him—how sensitive he was, how easily he could be wounded—and that made her feel closer to him, and also powerful, because once she knew how to hurt him she also knew how he could be soothed.

The writing of the story seems intentionally vague, borderline amateurish, and Margot’s reactions are cringe-worthily familiar. But the greater strength of the story is that you could swap out “Margot” and sub-in “I,” and the story could be, without much of a stretch, a first-person essay on Medium headlined, “The real reason women can’t ever break the cycle of self-blame,” or “Why I’m leaving Tinder.” Taken at face value, the story could be a very long Facebook status or a Reddit post, with a final line that winks exaggeratedly to readers ready to agree with the poster.

And indeed some commenters seem to be reading the story that way: Like any other piece of internet “content,” calling the story “a piece,” talking about the characters as if they are real. Some critics are treating “Cat Person” like it’s a clear-cut argument against men—no matter how well-intentioned or flawed or overweight—and in support of all women—no matter how rude or inexperienced or self-satisfied—and not like a piece of fiction that can hold multiple interpretations.

Fans are sharing the story with the equivalent of arrows saying “IT ME”; confused men are posting comments that say the equivalent of, “Can someone explain this to me?” or “Margot can go screw herself, go Robert”; and critics are treating the story like a think-piece—remarking that the story seems tone-deaf on obesity and Margot’s privilege. The story captures that enviable beast that combines the “me too” share and the hate share. Because the characters are not real victims of assault, even more men than usual feel free to tell the fictional Margot she’s in the wrong, which drives more discussion and makes the story cycle more visibly through Facebook’s algorithm.

The timing, too, is key. Against the backdrop of endless real articles describing instances of sexual harassment and abuse by powerful men, much of this story reads as true crime. A wary reader sees rape or assault lurking behind every early comment from Robert, the shadow of Harvey Weinstein or Louis CK cast by his repeatedly mentioned paunch.

We expect salaciousness and ready-made villains in our articles, so we feel a deep sense of foreboding as Robert buys Margot a lighter with a frog head, as he kisses her on the forehead and calls her “sweetheart.” And people (women) following real sexual allegations closely—reading them line by line to affirm the horror they know they’ve lived their entire lives—are used to quickly shooting off an email and link to their sisters, friends, colleagues, to say, “You have to read this.”

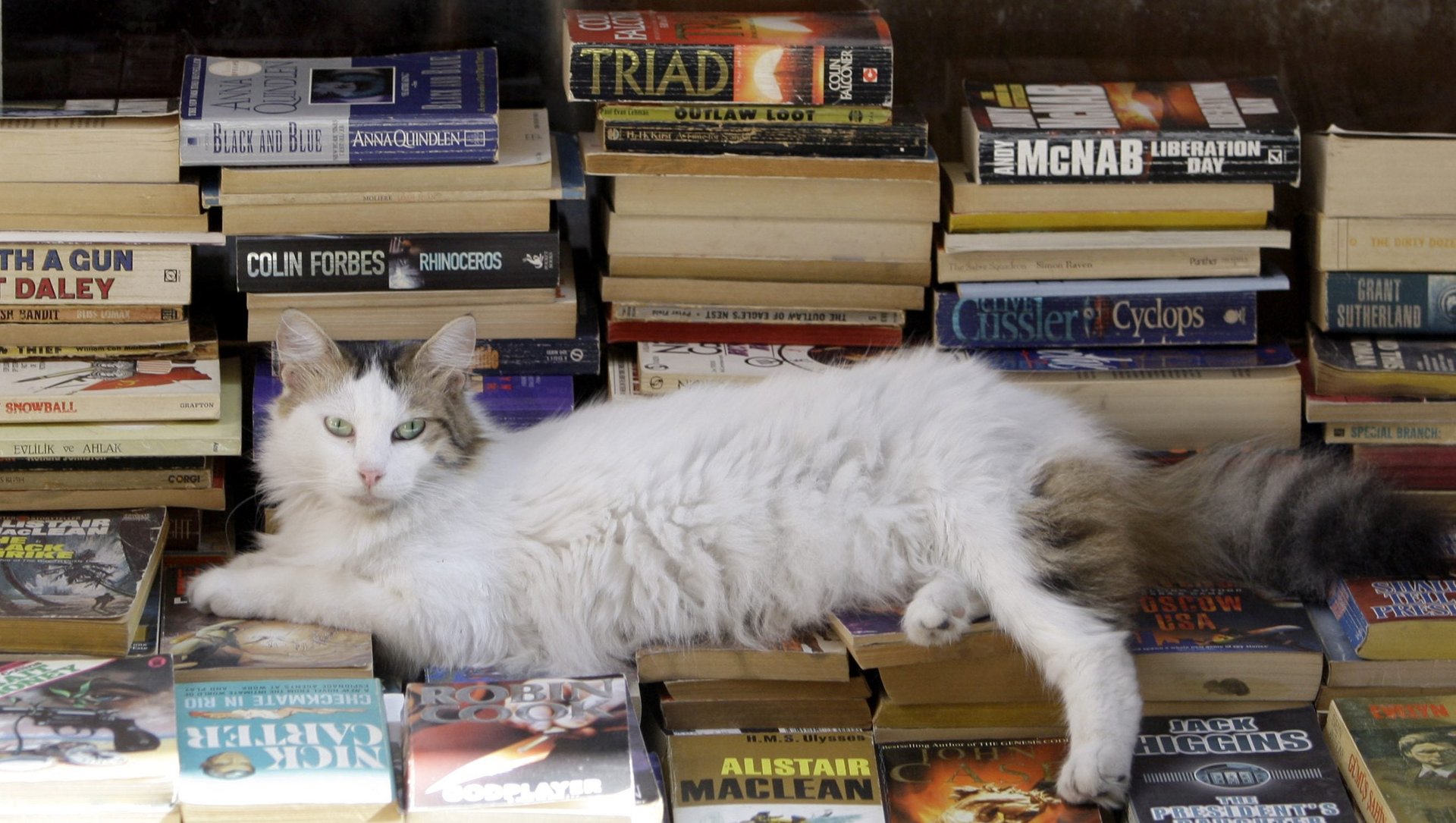

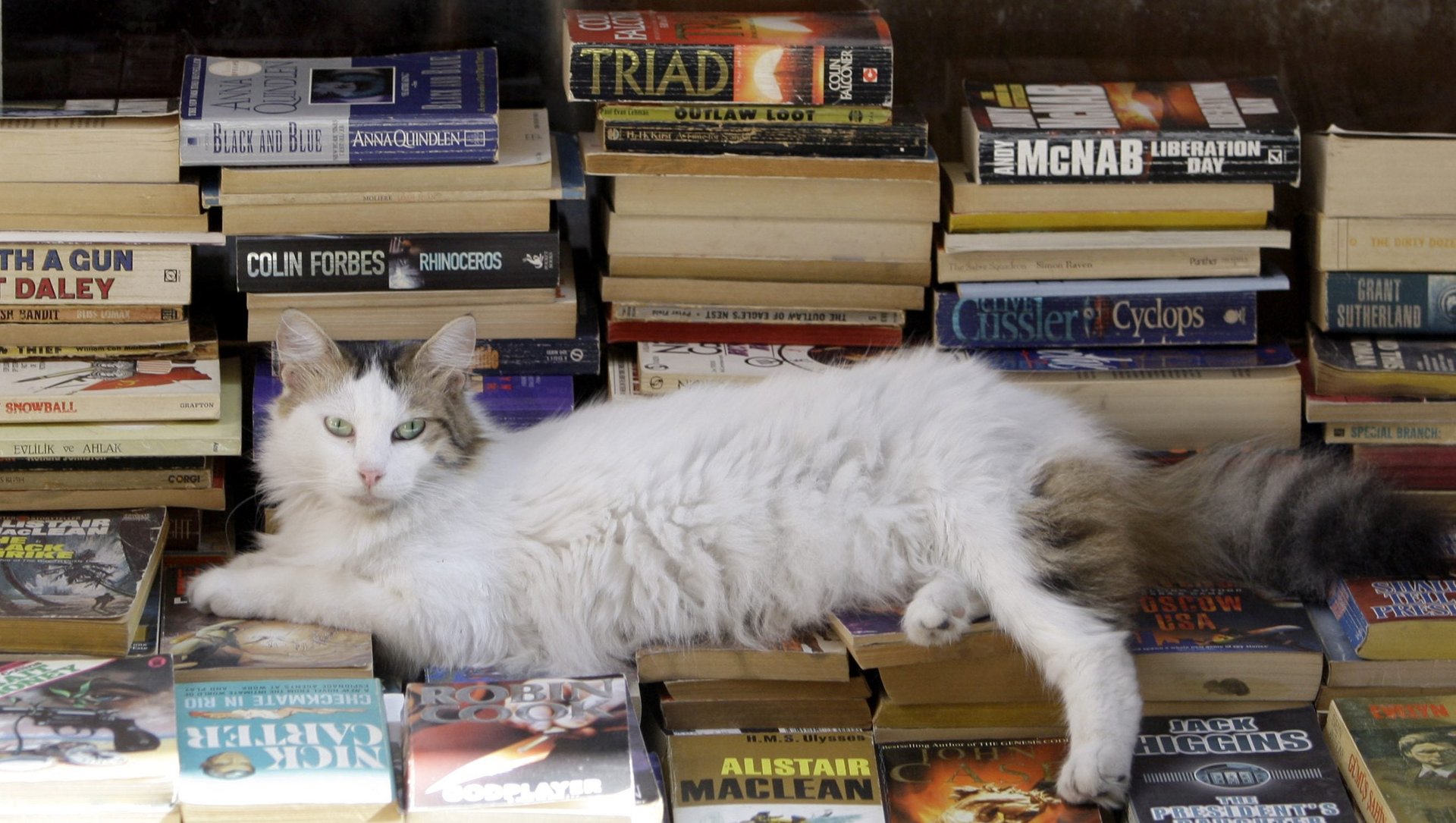

With the exception of the strangely stock share image for the story, “Cat Person” is veritable internet catnip. For most of the story, there’s an uncomfortable ambiguity that works as fiction. But as a short story on the internet in this moment, the overall concept works even better. Not because it’s an investigation of one particular named man. Rather, because it’s about so many unnamed women who’ve found themselves socially stuck, unwilling to make a man uncomfortable and afraid their rejection would have brutal repercussions—only to find out it’s just deep unease they’re left behind with. And it’s about the unnamed men listening and watching, uneasily.

This post has been corrected to reflect that “Cat Person” was first published online on Dec. 4.