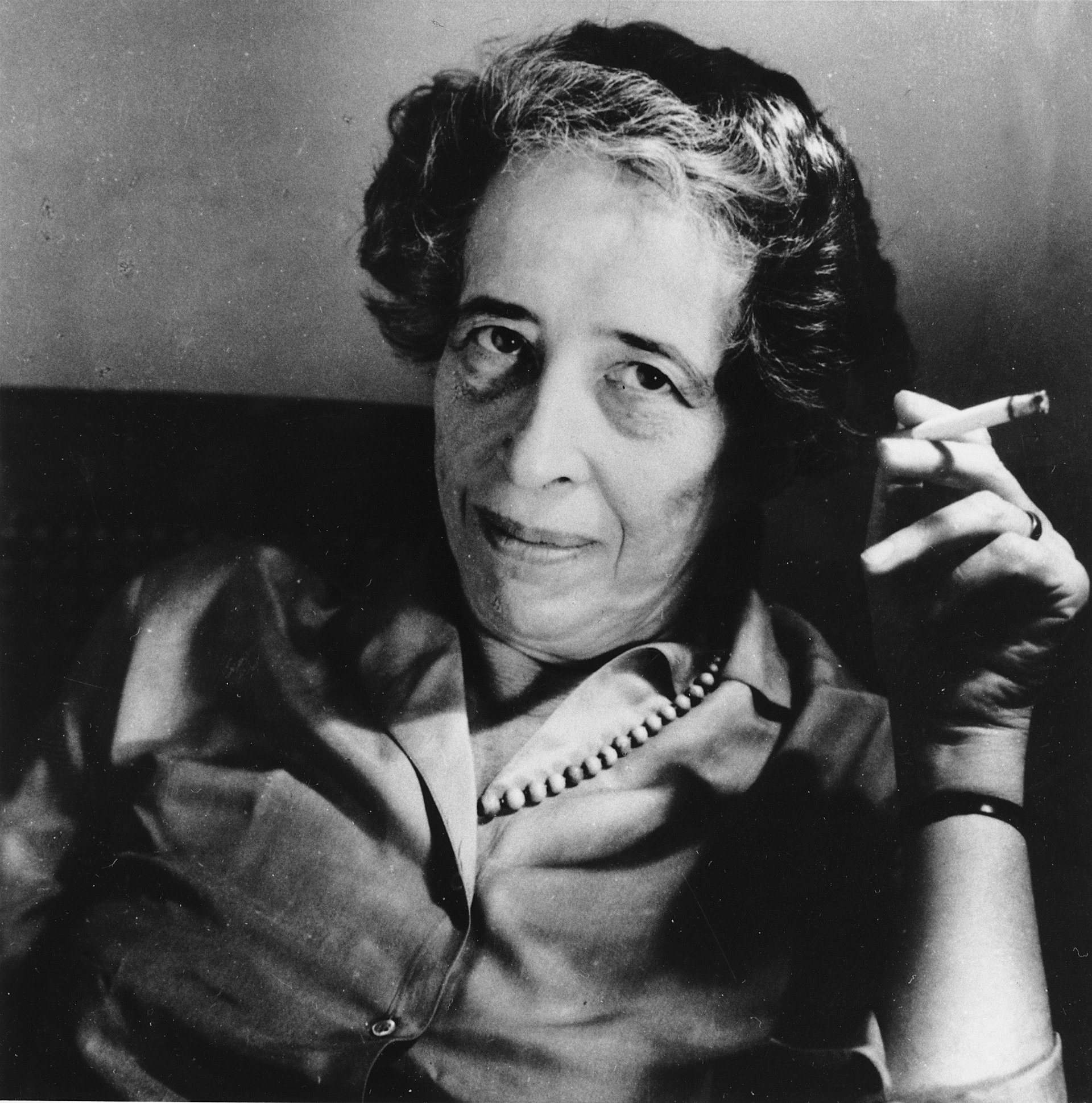

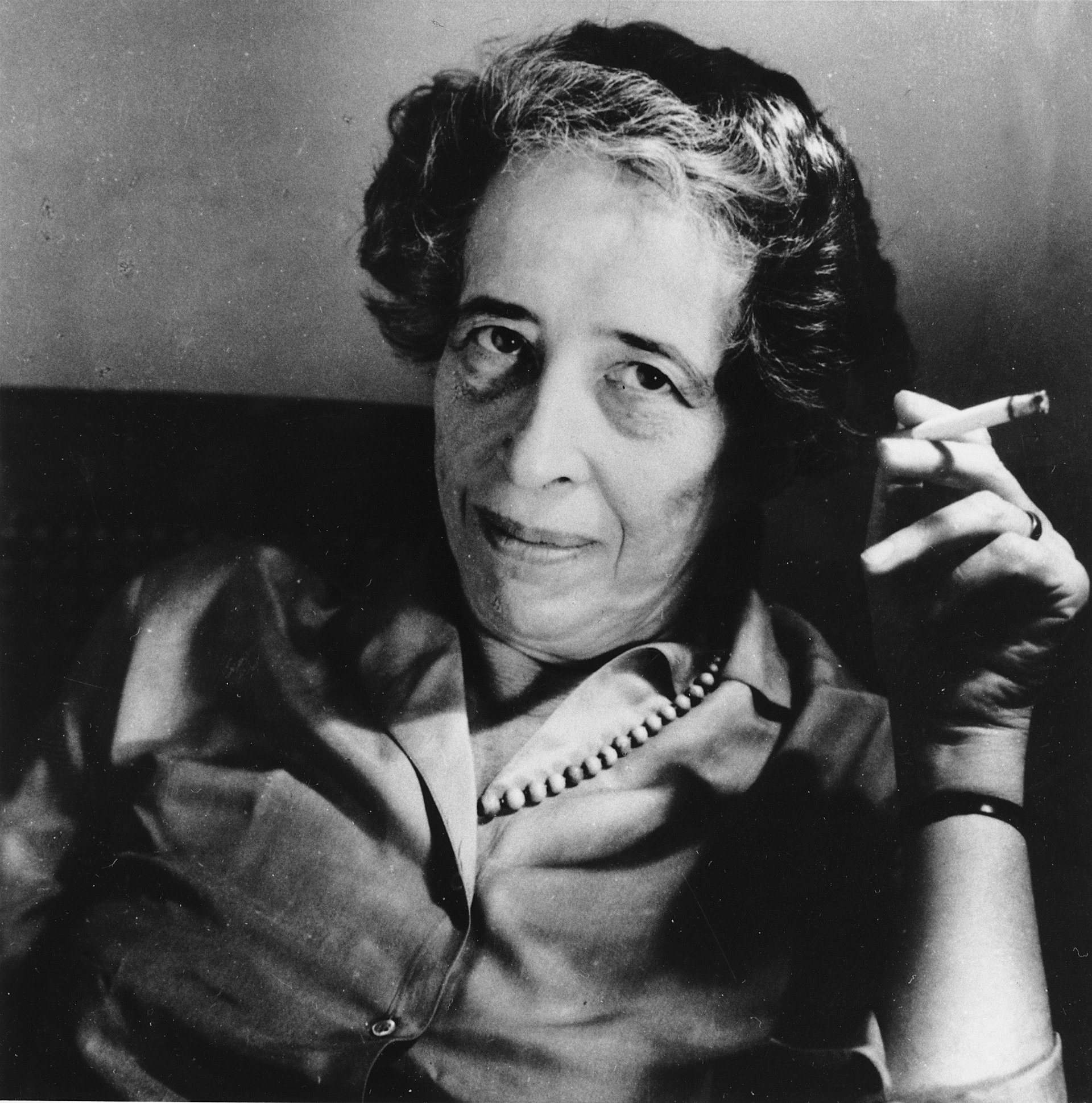

Hannah Arendt was the philosopher to reference in 2017

Resurgence in the popularity of a deceased philosopher is usually a cause for celebration. In the cause of Hannah Arendt, the reasons for renewed interest offer less to celebrate.

Resurgence in the popularity of a deceased philosopher is usually a cause for celebration. In the cause of Hannah Arendt, the reasons for renewed interest offer less to celebrate.

Arendt, whose most famous work The Origins of Totalitarianism dissects the rise of Nazism and Stalinism in the 20th century, has become the go-to thinker to cite this past year as Americans struggled to come to make sense of Donald Trump’s presidency.

The Arendt frenzy was first noticeable just days after President Trump’s January inauguration, when The Origins of Totalitarianism sold out on Amazon. In March, Roger Berkowitz, who founded and runs the Hannah Arendt Center, reported “an unprecedented surge of over 100 new memberships” in a piece for the LA Review of Books, adding that “our virtual reading group on The Origins of Totalitarianism has more than doubled in size.”

Interest in Arendt did not fade throughout the year. In February, Quartz referenced Arendt’s work on political lying to show why Kellyanne Conway’s reference to “alternative facts” were nothing to laugh about.

BBC Radio 4’s In Our Time devoted an episode to Arendt’s work, The Guardian explored whether we should be applying lessons from Arendt to Trump’s politics today, while Vox and The Times Literary Supplement devoted their own think pieces to Arendt. There were articles on her connection to everything from the refugee crisis to the New York Times’ normalizing profile of a Nazi.

There were also articles that hit back at the sloppy thinking or mistakes in this surge of Arendt articles. Emmett Rensin wryly describes the Arendt phenomenon as “a voice came howling out of the past, highlighted in pull quotes and conveyed in memes,” in Outline.com. “The words are difficult to make out at first. They’re half-remembered, if remembered at all — Did I do the reading that week of college? A quick Google provides clarity. Of course: The woman is Hannah Arendt, and she has come back from the wilderness to deliver us a message: Fascists are bad news.”

Some skepticism of the most simplistic Arendt-mania is warranted. Sure, president Trump clearly exhibits nationalist policies and a loose grasp of the truth. And, as Arendt’s work shows, we should always be wary of the rise of totalitarianism. But history never neatly repeats itself, and Arendt’s work on Nazism is no neat guide to Trump’s popularity.

In Berkowitz’s LA Review of Books piece—one of the best articles of the year on Arendt—he explores how some instincts among the privileged left wing can also be seen through Arendt’s lens. “It is hard not to wonder what Arendt would think of the wild success of The Sopranos, House of Cards and The Daily Show—shows in which the self-proclaimed elite celebrate and laugh at the exposure of the obvious hypocrisy of businessmen who are gangsters and politicians who are businessmen,” writes Berkowitz.

Arendt’s work is always worth reading, and is certainly still relevant today. But Trump is not the only reason to read Arendt. The political tactics and instincts she writes about are everywhere, not just in the White House.