Hubert de Givenchy, like many great artists, will be remembered for just one thing

Even with the right skills, few artists can make a career from a dream. Getting recognition for abilities is an uphill battle, and the luckiest—those who gain a lifetime of international success—tend to only be remembered for a single thing after death.

Even with the right skills, few artists can make a career from a dream. Getting recognition for abilities is an uphill battle, and the luckiest—those who gain a lifetime of international success—tend to only be remembered for a single thing after death.

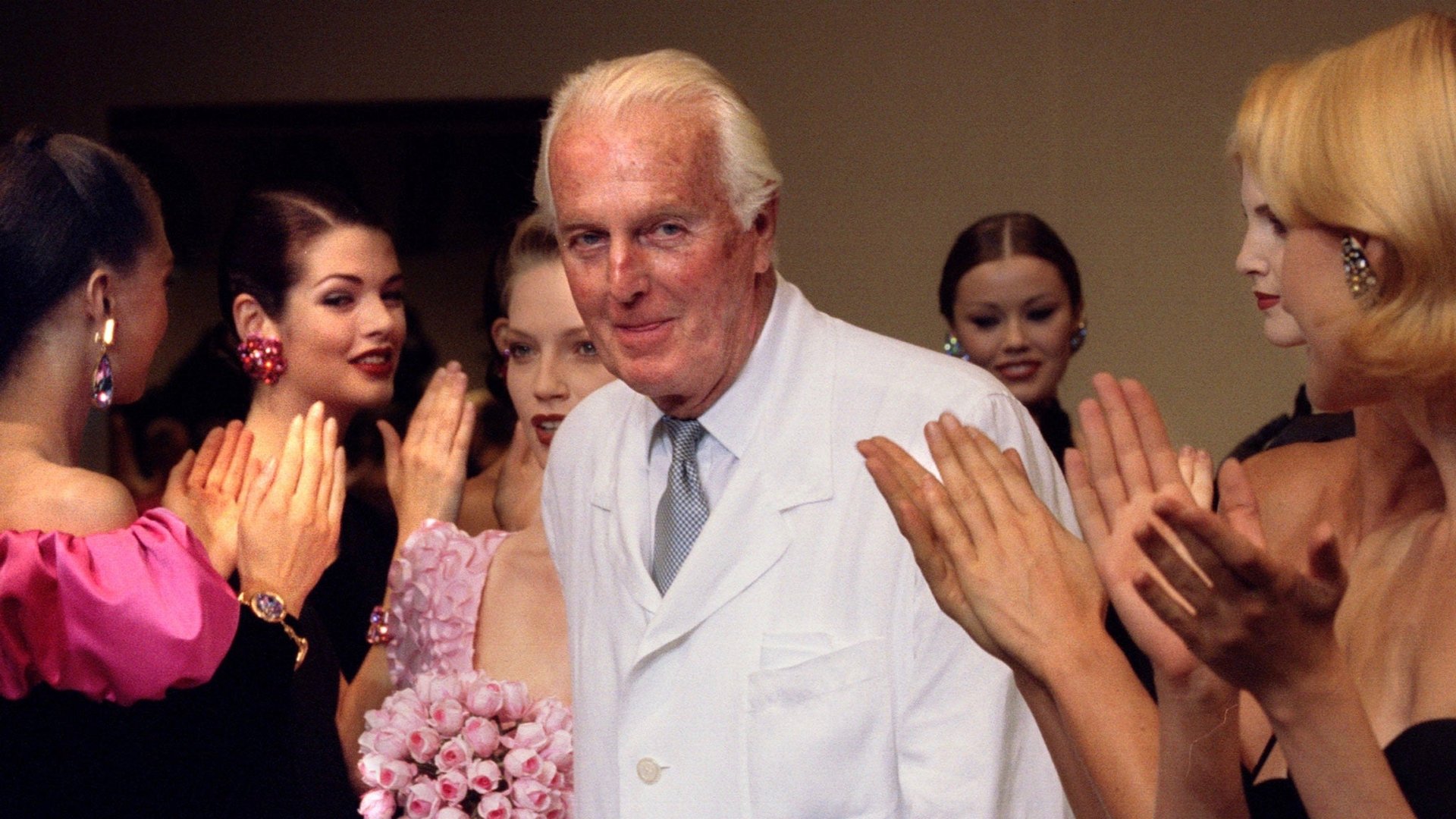

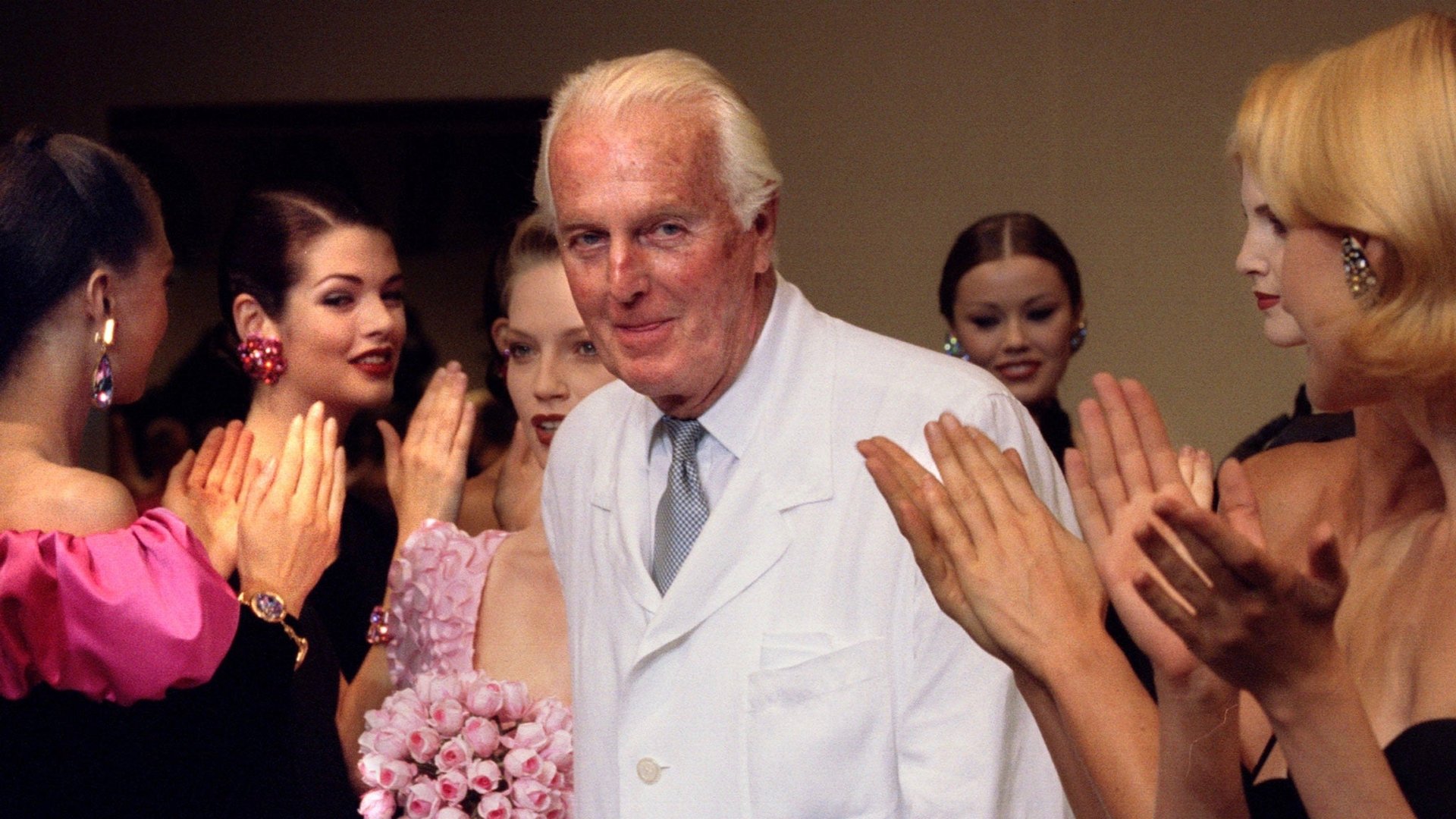

This will likely be the bittersweet fate of the very lucky Hubert de Givenchy, a fashion designer and French aristocrat whose ideas may have influenced your outfit today. The iconic designer died on March 10 at age 91, after rising to worldwide fame in the 1950s and 1960s and contributing to his still-thriving house until 2014.

Givenchy’s early and later work remains contemporary. In fact, we have him to thank for fashion separates—that is, the now very common idea that a woman’s wardrobe can be modular, comprised of complementary parts that all fit together into different looks instead of complete outfits.

But we’ll remember him for one dress worn by a single unforgettable actress that’s actually a nod to another designer, Coco Chanel, creator of the Little Black Dress—or LBD. Audrey Hepburn wore a long, simple black sheath dress with a slit up one side, and long black gloves, in the 1961 movie Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Givenchy designed the dress, and many of Hepburn’s subsequent looks on film and in life—as well as pieces for Jackie Kennedy and Grace Kelley.

“Coco Chanel may have originated the Little Black Dress, but it was Givenchy, thanks to Hepburn’s both louche and devastatingly sharp inhabitation of an albeit-elongated version of the garment in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, that made it iconic,” writes Tim Teeman in a Variety piece titled “Givenchy’s Brilliance was More than just Breakfast at Tiffany’s.”

The writer’s concern is that Givenchy’s many other sartorial contributions will be forgotten because of one woman in a single cinema sensation—which would still put Givenchy’s reputation in an enviable state. This designer’s fate is no different than that of other artistic greats who innovate for decades but are mostly known for only one work. Take Andy Warhol’s classic Campbell Soup can paintings, for example.

Warhol didn’t just do screen prints of items that could be found in a supermarket, although those are the paintings we best recall. He also transformed the art world with the concept of superficial works that were sneakily substantive for their comment on the culture. Equally key, he also spawned a generation of artists in many genres by creating The Factory for artistic experimentation and production. And because of him, we people of the future, all expect at least 15 minutes of fame—although some now dispute the claim Warhol famously said, “In the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes” (a challenge that itself proves the point little endures).

Similarly, literary history is riddled with major contributors who left behind many great works but are barely recalled for one. The French writer Marguerite Duras made avant-garde films, wrote plays and books, fiction and non-fiction, and was widely admired throughout the 20th century. But only one work, a novel called The Lover, which she wrote at age 70 in 1984 and became a major movie production, made it big. Now, Duras is still a small part of our barely enduring cultural memory.

Those are the lucky ones. As the band Wilco sings in the heartbreaking Late Greats, the best works of all never reach us, let alone are remembered. “The best band will never get signed. The Kay-Settes starring Butchers Blind,” croons Wilco’s singer Jeff Tweedy. “So good you won’t ever know. They never even played a show. Can’t hear them on the radio.”