China’s William Gibson is a sci-fi writer wrestling with problems from pollution to patriarchy

The village of Guiyu in China’s southern Guangdong province is known as the world’s e-waste capital. Thousands of locals have for over a decade been making a living by extracting precious metals like gold and silver from old computers, cell phones, and batteries shipped from across the globe. There, the air is toxic, the water is black, and the children have lead poisoning.

The village of Guiyu in China’s southern Guangdong province is known as the world’s e-waste capital. Thousands of locals have for over a decade been making a living by extracting precious metals like gold and silver from old computers, cell phones, and batteries shipped from across the globe. There, the air is toxic, the water is black, and the children have lead poisoning.

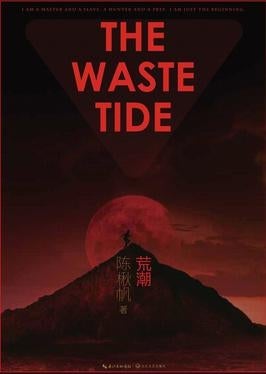

Chen Qiufan, born in nearby Shantou city, learned about Guiyu’s environmental nightmare from a friend working in the electronics recycling industry. In his debut novel The Waste Tide (2013), 36-year-old Chen turns Guiyu into “Silicon Isle,” a homophone of the village’s name in Chinese. In the cyberpunkish wasteland, migrant workers dismantle prosthetic limbs, eyes, and even heads dumped by rich people, who can upgrade their body parts much like we upgrade our iPhones.

Chen, who also goes by the name Stanley Chan, is among a new generation of Chinese science fiction writers who have been making a splash on the world stage in recent years. Liu Cixin’s book The Three-Body Problem won a prestigious Hugo Award for best novel in 2015, and in 2016 Hao Jingfang’s Folding Beijing won best novelette. Chinese sci-fi often hits close to home for domestic readers—the stories are typically focused on problems specific to the country, such as censorship, pollution, and social inequality. Authors like Chen often set their stories in the near future, exploring how new technology devours humanity in an otherwise seemingly familiar Chinese society. In other words, the dark themes underpinning their sci-fi stories often read more like non-fiction.

Science fiction is a “thought experiment in which you build a world, and throw characters into it to deduce the possibilities,” Chen said in a recent interview on the sidelines of Melon Hong Kong, one of Asia’s biggest sci-fi conferences. “I’m a problem-oriented writer. I want to explore problems in real life, ones brought to us by technology development.”

The future is already here

Chen is often dubbed “China’s William Gibson,” for his realistic style that is reminiscent of the Canadian-American cyberpunk author whose seminal 1984 work Neuromancer, a critique of 1980s capitalism set in a dystopian Japan, is credited with popularizing the concept of cyberspace. In 1997, a 16-year-old Chen published his first short story Bait in China’s most influential sci-fi magazine Science Fiction World (link in Chinese). The story is about humans becoming slaves to new technology brought by an alien species, and criticizes the idea of consumerism.

Chen says one of Gibson’s quotes perfectly captures the reality of life in China: “The future is already here—it’s just not evenly distributed.” The Matthew effect—whereby the rich get richer and the poor get poorer—is everywhere in China, he explains. For those at the bottom of the pyramid, he says, it’s becoming harder and harder for them to climb up the hierarchy.

In his 2006 short story The Fish of Lijiang, the protagonist, a stressed-out office worker, is forced to take a therapeutic leave of absence in the tourist town of Lijiang in southwestern Yunnan province, famed for its brilliant blue skies and old alleyways. The scenery in Chen’s Lijiang, however, isn’t real but is instead enabled by technology such as virtual reality (VR). The protagonist has a romantic encounter with a nurse, who later turns out to have had sex with him only in order to “harmonize” their biorhythms. Chen writes:

“I have a car, a house—everything a man should have, including erectile dysfunction and insomnia. If happiness and time are the two axes of a graph, then I’m afraid that the curve of my life has already passed the apex and is on its inexorable way down to the bottom.”

The story is about “Chinese people’s anxiety about speed,” says Chen. “Everyone is afraid that he will lag behind others, and everyone wants to get on the train to financial independence.”

A tech exec by day

As a child, Chen was an avid reader who often finished a book a day, and he became interested in science fiction because of French novelist Jules Verne, he says. Despite getting good grades in physics, he graduated from the prestigious Peking University with a bachelor’s degree in Chinese literature. Soon after, he worked as a salesperson at a Shenzhen-based property firm, but quickly realized he hated the job so much that he had to quit. “Even today, I feel nauseous when I see any promotional materials about real estate,” he wrote on Chinese Q&A site Zhihu (link in Chinese) in 2012, adding that real estate ads in China seem like “the biggest fraud of the century” to him.

Chen then entered the tech world in 2006. A former employee with Google and Baidu, he is now chief marketing officer at a Beijing-based startup focused on motion capture and VR. With over a decade of experience in tech, Chen often references the latest technology in his stories. In his novel The Waste Tide, written between 2011 and 2012, for example, he introduces a gadget similar to Google Glass. In his short story Consecration, he imagines a sort of anti-Photoshop app, which can reverse overly doctored selfies back to the original with one tap on the phone. He is currently working on a short story about blockchain.

Many of Chen’s short stories have been translated by Chinese-American sci-fi writer Ken Liu, and can be found in major sci-fi magazines such as Clarkesworld, as well as in Liu’s anthology Invisible Planets. The English version of The Waste Tide will be published in July 2019.

In Chen’s eyes, China is so vast and complicated that it is a great source of inspiration for sci-fi writers. Outside his full-time job, Chen travels extensively to meet people from all walks of life, and writes whenever he has a chance during his commute. In his 2006 short story The Smog Society, Chen imagines a world where the smog index is correlated with people’s happiness—for example, investors who lost money in a stock market crash can generate smog to envelop the stock exchange. In 2009’s The Year of the Rat, he tells the story of unemployed college graduates being recruited by the military to kill a species of pet rat that can stand on two feet. In 2012’s G Represents Goddess, the vagina-less female protagonist is reduced to being a subject of orgasm studies as well as a male sexual fantasy. All of these stories revolve around problems that are all too real to Chinese people: pollution, youth unemployment, and the patriarchy.

Chen has a robot that is learning to imitate his writing. Although at this stage the robot produces mostly gibberish, he plans to use it to write scripts for AI machines featured in his own stories. Someday, “maybe my readers will like its style rather than mine,” he jokes.

Live long and prosper

Chen is planning to quit his tech job to become a full-time writer, but in the meantime, he has started his own production studio to adapt his stories into screenplays. He is currently working with iQiyi, one of China’s most popular video streaming sites, to produce an online series based on his short story Virtual Love, which imagines a world where all romantic relationships are matched by big data. Production is expected to start this year.

Science fiction, though emerging, is still a small player in China’s movie industry. In 2017, the genre took in around 200 million yuan ($32 million) at China’s box office, 14% of the total, compared to 32% in North America, according to research firm Ent Group (link in Chinese). Of that, only 5% was contributed by domestic titles. In 2016, the film adaption of The Three-Body Problem was shelved, put off indefinitely due to its Chinese rightholder’s internal shuffling, but the Financial Times reported recently that Amazon is in talks to pay $1 billion (paywall) to acquire the rights to produce three seasons of episodes based on the books.

Despite The Three-Body Problem’s success, Chen believes that China is still far from becoming a sci-fi powerhouse as it doesn’t have as many authors, screenwriters, and producers as Western countries do. “There’s the pinnacle, but the foundation is too weak,” he says.

Beyond that, he argues, “a world-class cultural product or phenomenon has to have a universal value.” In the West’s case, it’s about upholding personal values, freedom, and equality, themes that are always reflected in Hollywood movies, including sci-fi. But “China doesn’t have much of a consensus, except that it is to become the world’s biggest power.”

What can be China’s consensus then? Chen says it’s “harmony,” a word that shows Chinese culture’s emphasis on collectivism over individualism.

But “harmony” is also a term used by the Chinese Communist Party to justify its crackdowns on the internet and any form of dissent. In 2010, Google shut down its Chinese search engine as the company refused to comply with the government’s censorship regulations. A year later, then Googler Chen published his short-story collection Censored. In the preface, he refers to a Reporters Without Borders campaign that, by strategic pixelization, turns a photo of Barack Obama patting Hillary Clinton into one of him groping her. Chen says in the story that Chinese people are familiar with the idea that “censorship tells the wrong story.” He goes on to write, “When compared to the dark, heavily censored reality, science fiction can sometimes speak some truths, clarify some sense, and penetrate through heavy fog.”

Still, Chen says his stories are not an attack on China’s system, but a reflection of its reality, a mixture of good and bad. Politics is a rabbit hole that Chinese people usually don’t want to get into in public. But during a panel at the Hong Kong sci-fi conference, a moderator tossed a sensitive question at Chen and his writer peers: If you were to write a sci-fi story about a president for life, would you prefer a happy ending or a sad ending, and what is the line you would end the story with? The question refers to Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s recent move to scrap presidential term limits.

Chen was the only one to answer the question directly. He said it would be a happy ending with the final line, “Live long and prosper,” the famous quote from Star Trek’s Spock, his childhood hero. Was he being sarcastic or genuine? Chen later told me offstage that he would let readers decide for themselves.