In 1960, Philip Roth spoke on how to create fiction during a real-life political horror show

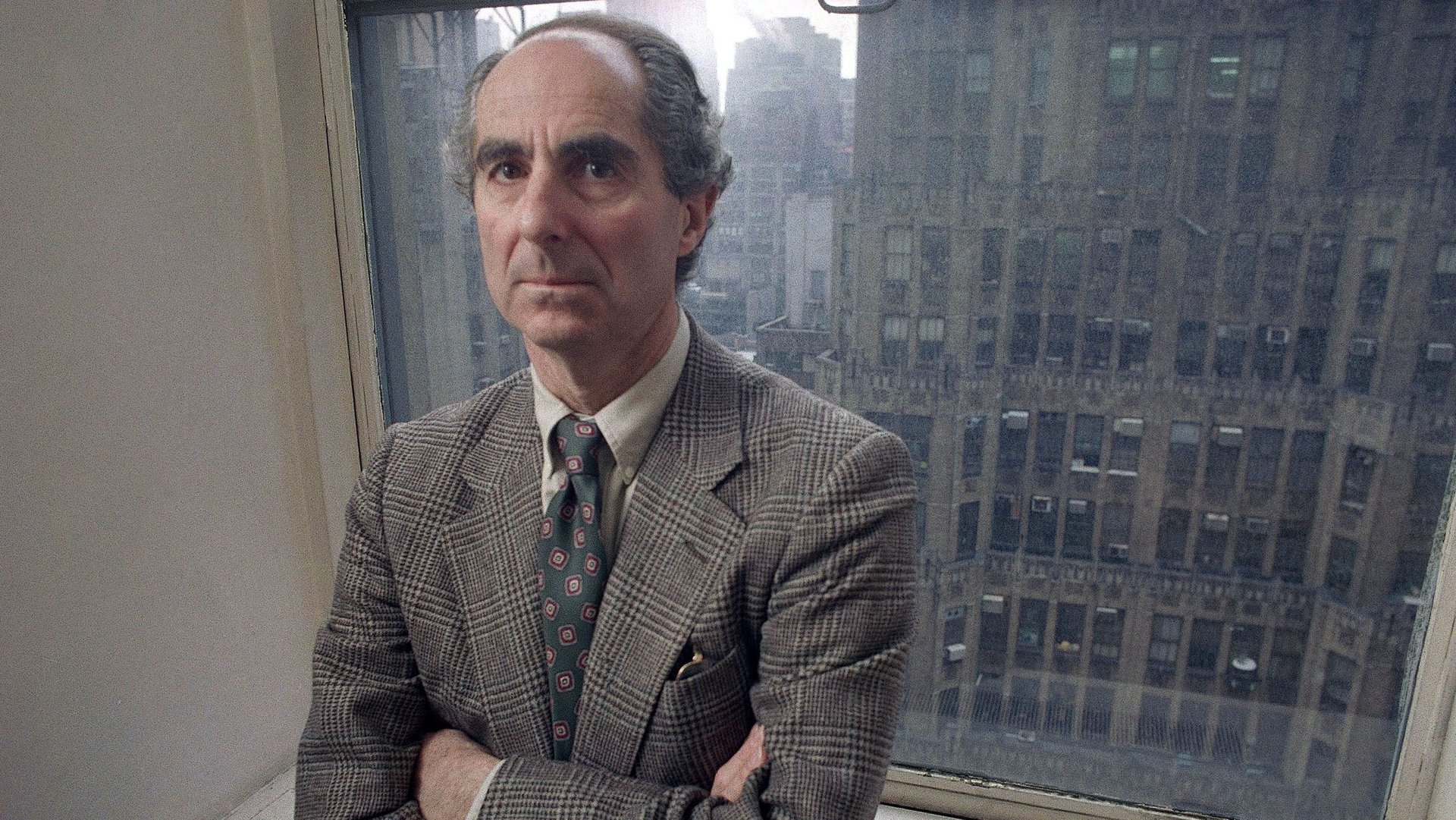

Philip Roth, one of the OG white dudes of American literature, has died. The prolific, ruthlessly funny, sometimes cranky writer was 85.

Philip Roth, one of the OG white dudes of American literature, has died. The prolific, ruthlessly funny, sometimes cranky writer was 85.

Roth was the author of Sabbath’s Theater, American Pastoral, and Portnoy’s Complaint. He was proudly American and frequently took on the burden of portraying the post-war country in his books. That doesn’t mean it came easy. In 1960, Roth gave a lecture at Stanford University, in which he describes the challenge of being a writer of American fiction when real life has stretched beyond the point of absurdity.

Roth’s anguish from nearly 60 years ago resonates to many today: “The daily newspapers, then, fill us with wonder and awe (is it possible? is it happening?), also with sickness and despair. The fixes, the scandals, the insanity, the idiocy, the piety, the lies, the noise…” he writes.

Born in 1933 and having served in the army for two years before writing that lecture, Roth was filled with incredulity at the likes of Roy Cohn, the American lawyer who helped oversee the McCarthy trials, and Sherman Adams, the presidential aide who got fired from the White House for accepting a vicuna coat as a gift.

One reaction, says Roth, is to not engage at all, to throw one’s hands up and say with cool detachment, this is all a zoo, to say, “What can the writer do with so much of the American reality as it is?… The whole thing is a joke. America, ha-ha.”

Another approach, he said, is not to write at all. “One would think that we might get a high proportion of historical novels or contemporary satire—or perhaps just nothing. No books,” writes Roth.

Ultimately, he points to a way for writers to not give up fiction altogether in such strange times:

However, that our communal predicament is a distressing one, is a fact that weighs upon the writer no less, and perhaps even more, than his neighbor—for to the writer the community is, properly, both his subject and his audience. And it may be that when the predicament produces in the writer not only feelings of disgust, rage, and melancholy, but impotence, too, he is apt to lose heart and finally, like his neighbor, turn to other matters, or to other worlds; or to the self, which may, in a variety of ways, become his subject, or even the impulse for his technique. What I have tried to point out is that the sheer fact of self, the vision of self as inviolable, powerful, and nervy, self as the only real thing in an unreal environment, that that vision has given to some writers joy, solace, and muscle.