The accidental trick of light that made a master cinematographer’s career

What made James Wong Howe one of the greatest Hollywood cinematographers of all time was talent, perseverance, and innovation. But he caught his biggest break by accident.

What made James Wong Howe one of the greatest Hollywood cinematographers of all time was talent, perseverance, and innovation. But he caught his biggest break by accident.

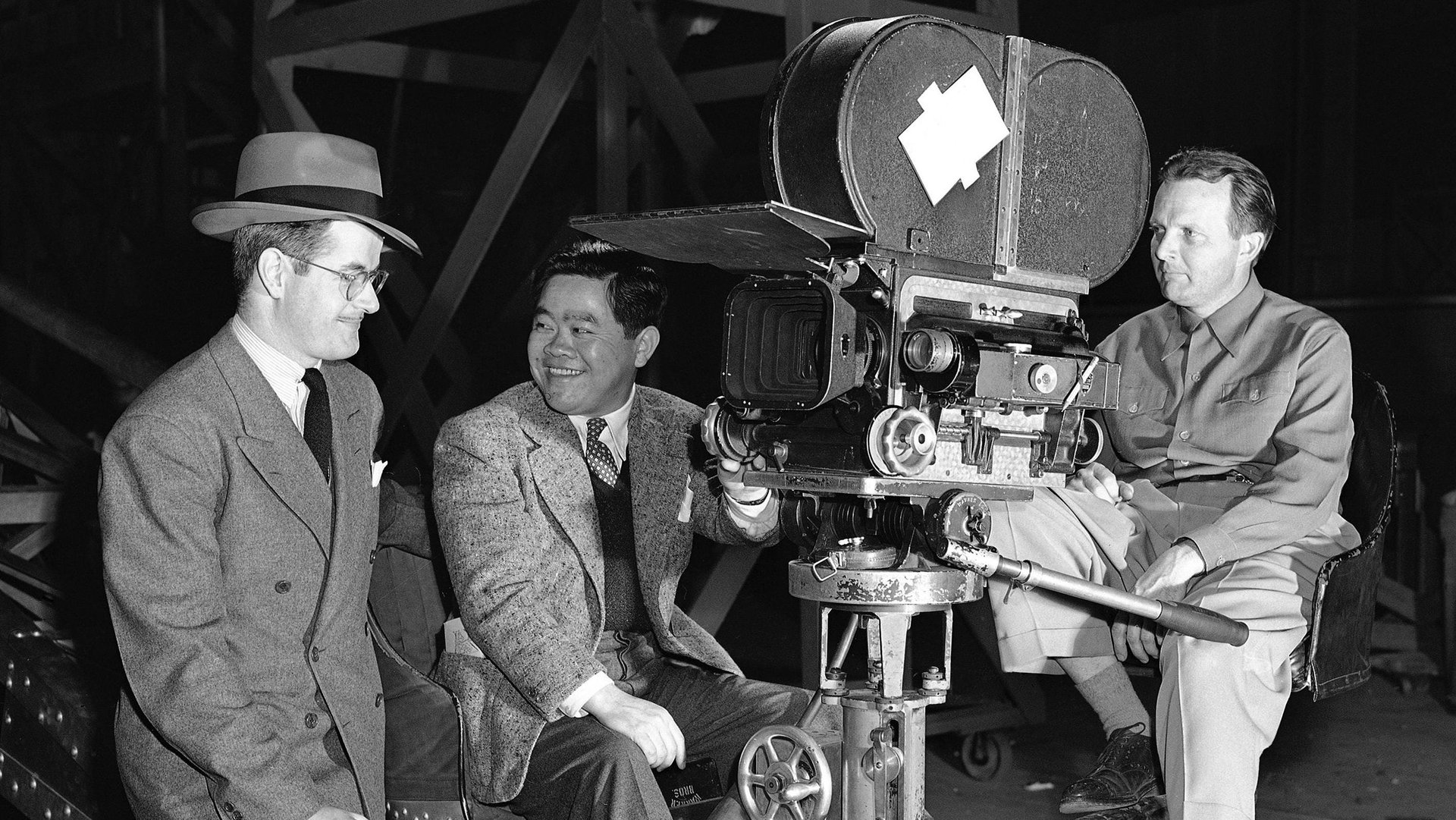

Today’s (May 25) Google Doodle is on the Chinese-born American cinematographer and master of lights who revolutionized filmmaking in the first half of the 20th century. A 10-time Oscar nominee, Howe began his career during the silent film and black-and-white eras, eventually moving on to sound and color film. He was the first non-white filmmaker admitted to the American Society of Cinematographers. He died in 1976.

Born in 1899 in China, Howe emigrated to Washington state when he was 5. Shortly after high school, Howe moved to Los Angeles and got his start in the industry, delivering stag films. He soon got a job at a film studio as a clapper boy, holding up the slate before each take. There, he was noticed by Cecil B. DeMille, the “founding father” of Hollywood, who made Howe one of his assistant cameramen.

As a side job, Howe took publicity photos for famous actors, and that’s when the legend was born. The cinematographer explained in 1970 how he accidentally discovered a lighting technique that would change Hollywood forever. Film critic Roger Ebert wrote up a speech Howe made at the Chicago International Film Festival for the Chicago Sun-Times that year, quoting Howe:

“One day I asked Mary Miles Minter, the silent star, if I could take her picture. She said ‘Sure, go ahead.’ “So I did, and a day after she got the prints she invited me to her dressing room. She said she wanted me to be her cinematographer. I asked why. She said because I made her eyes look dark. “Well, in those days we used black and white film that didn’t distinguish very well between blue and white. That was why you couldn’t shoot clouds in the sky. Mary Miles Minter had blue eyes, and they always came out pale on film. But in my pictures, they were dark and beautiful.”

The only problem, Howe said, was that he had no idea how he’d made her eyes dark. He finally decided it was because he’d been standing in front of a dark backdrop when he photographed her. Her eyes reflected the backdrop like mirrors. Eureka! So Howe hung a big black velvet curtain in front of his movie camera, cut a hole in it, and shot Mary Miles Minter through the hole. The result: Dark, beautiful eyes. “In those days Hollywood was a little colony and the gossip spread fast,” Howe said. “The word went around at cocktail parties that Mary Miles Minter had imported herself an Oriental cameraman, who hid behind a velvet curtain and magically made her eyes turn dark. After that, I was never out of work.”

Howe would go on to shoot dozens and dozens of films, working with the most esteemed actors and directors in Hollywood. He won the Academy Award for best cinematography twice, for The Rose Tattoo in 1955 and Hud in 1963.

Along the way, Howe pioneered a number of other techniques, including low-key lighting, wide-angle lenses, and hand-held camera operating. For a scene in the 1947 boxing film Body and Soul, Howe entered the ring on roller skates and held the camera himself.

Howe did all this at a time of extreme discrimination. He married Sanora Babb, a white novelist, in Paris in 1937, but the marriage was not recognized in California for another 11 years due to anti-miscegenation laws. He wasn’t even allowed to become an American citizen until the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1943, despite living almost his entire life in the US. Howe was “gray-listed” as a Communist sympathizer by the House Un-American Activities Committee and was forced to move to Mexico for a short time in the late 1940s.

Upon his return to America, he was welcomed back to Hollywood as one of the greats.