A Congolese artist’s fantastical cityscapes blend Wakanda and Wes Anderson

A new show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City will delight kids, Afrofuturists, and urban planning nerds alike.

A new show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City will delight kids, Afrofuturists, and urban planning nerds alike.

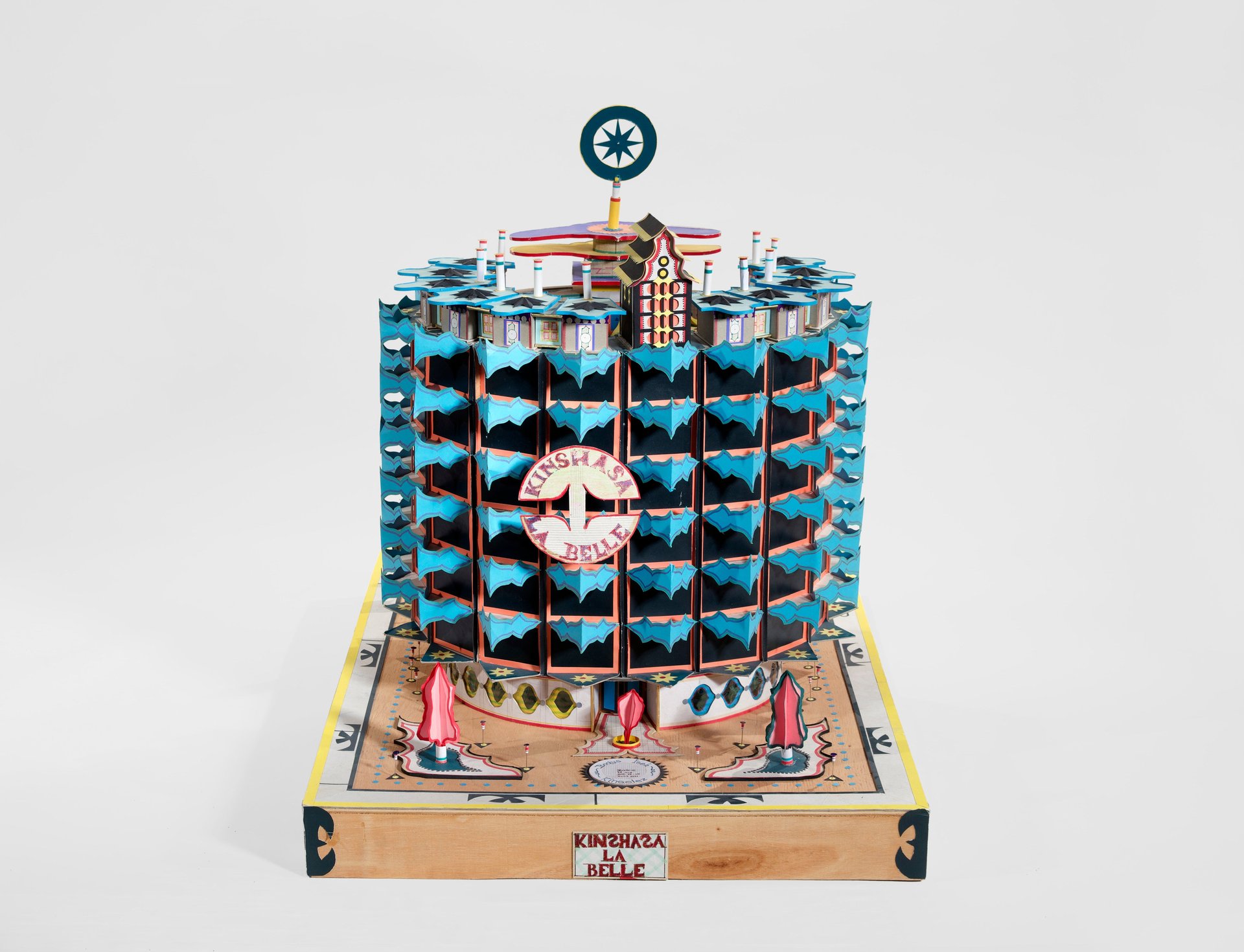

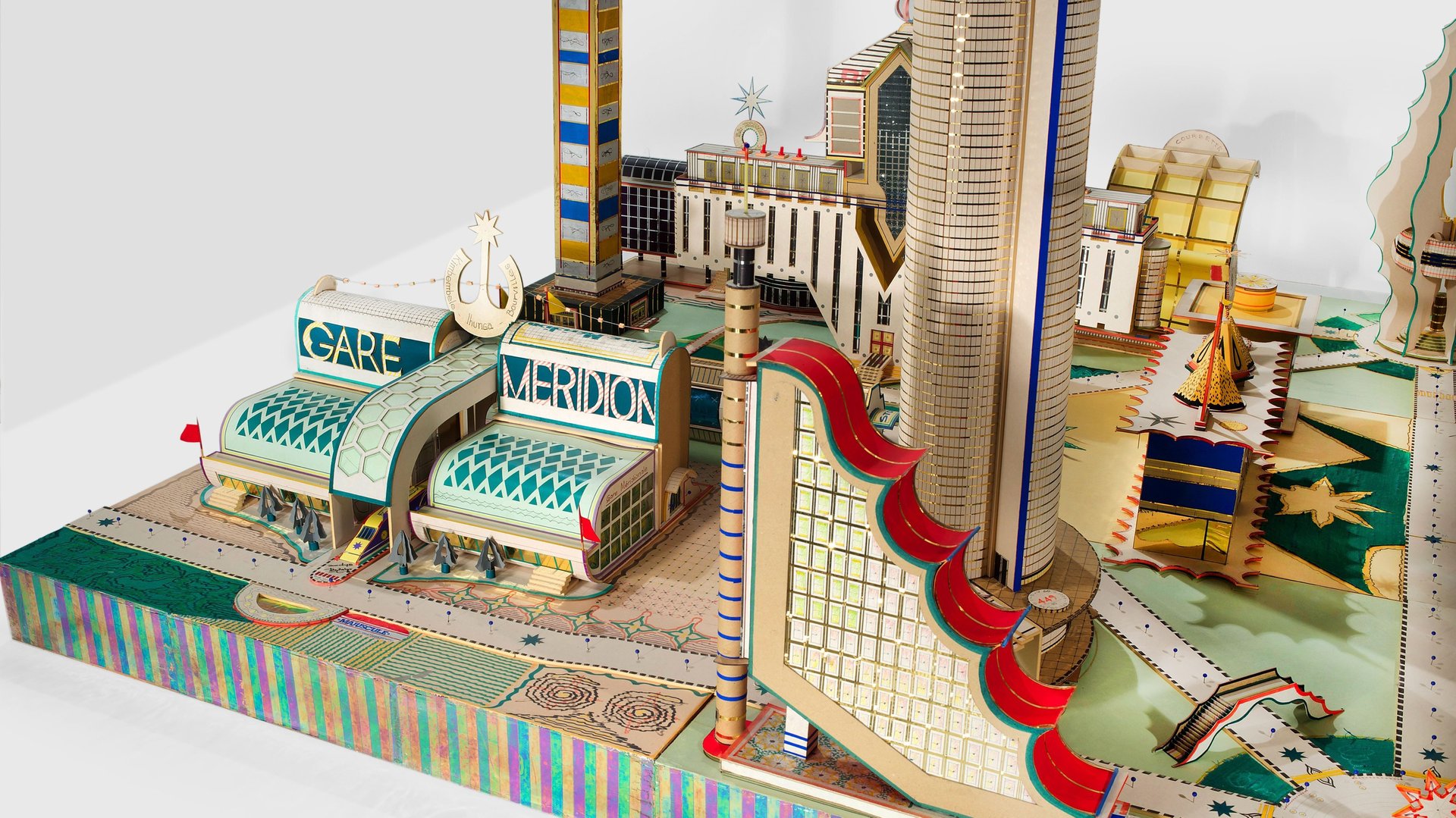

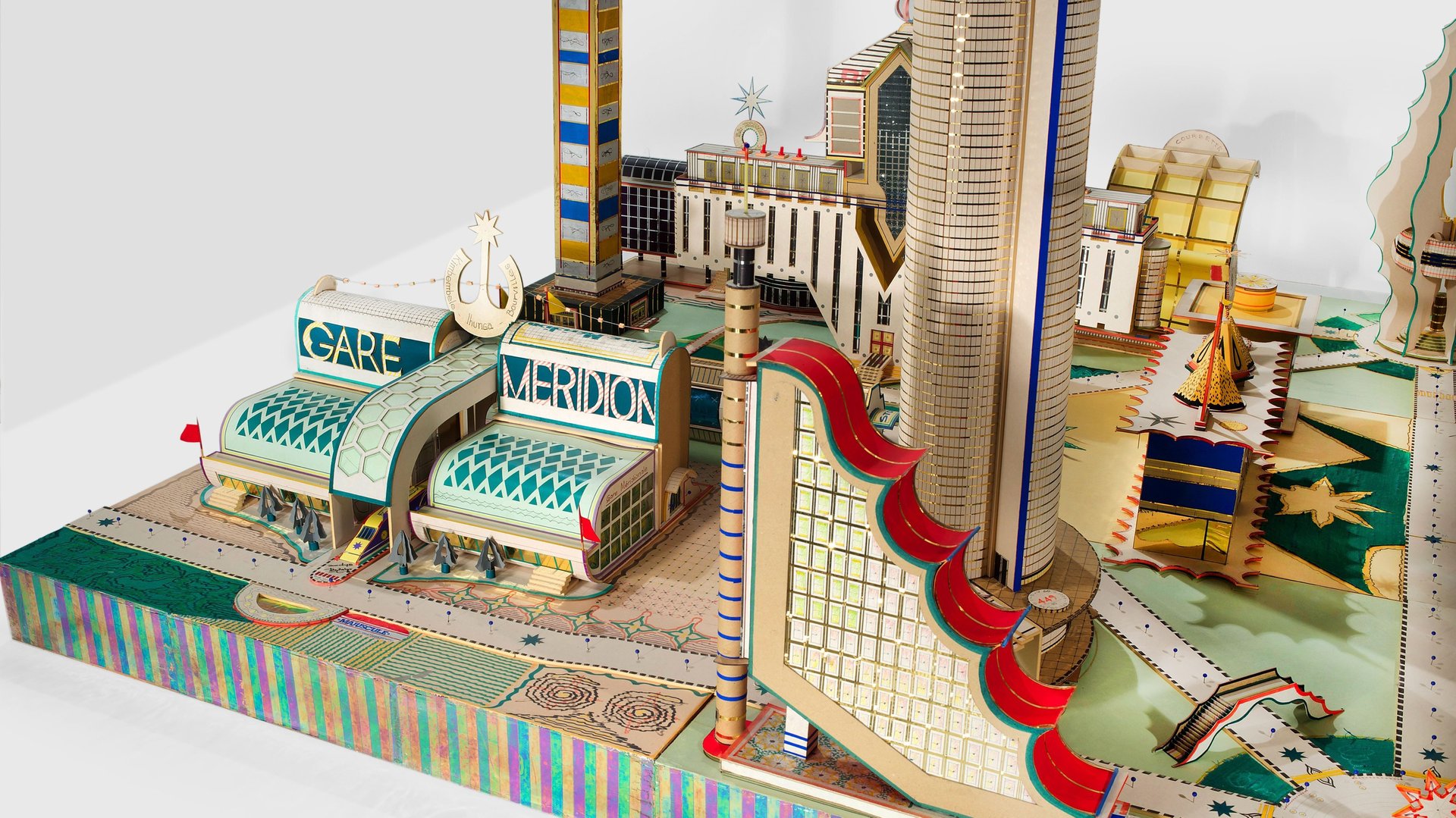

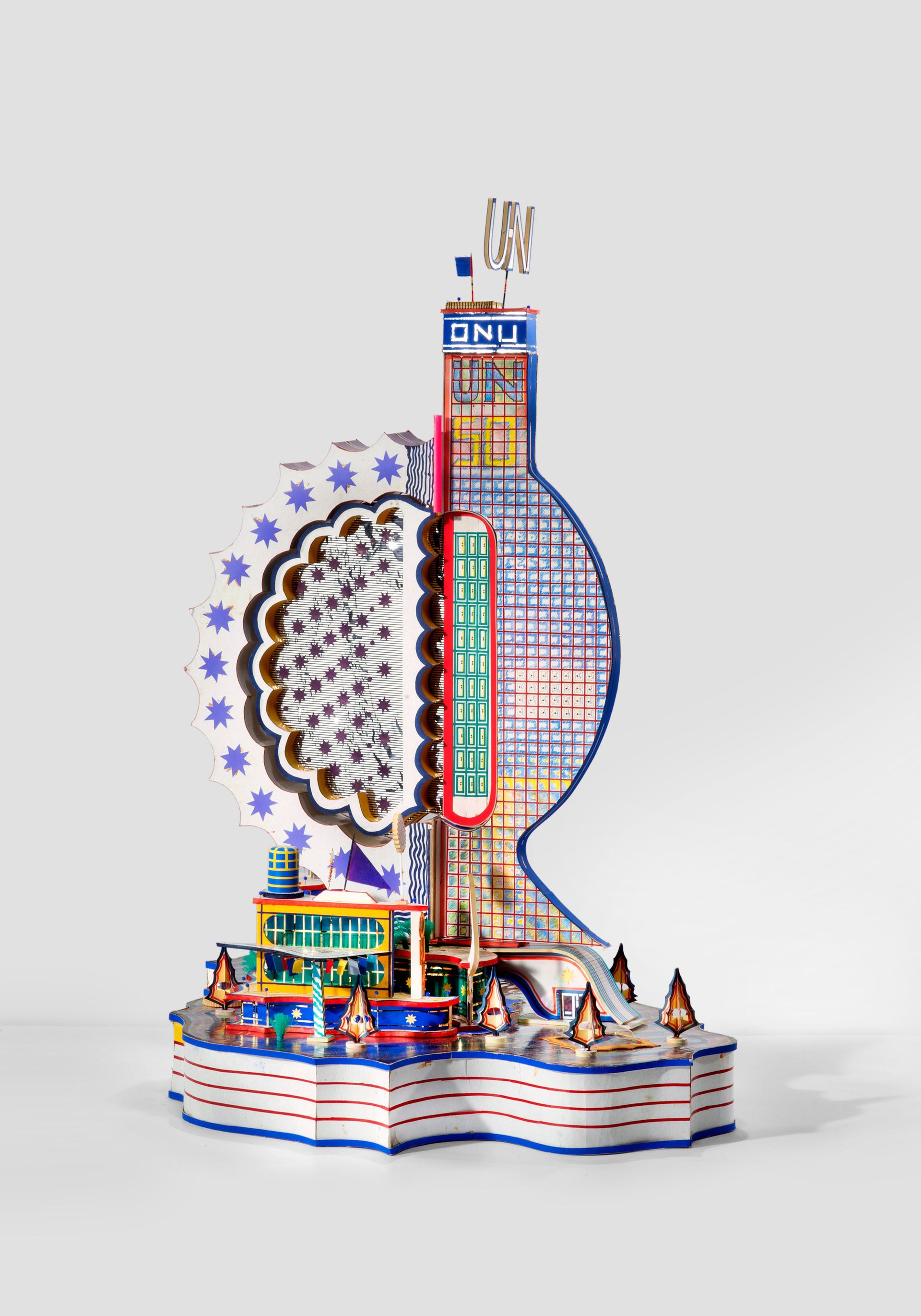

“City Dreams,” a retrospective of the Congolese artist Bodys Isek Kingelez, shows his vision of the world: A utopian antidote to corruption and suffering, through whimsical, technicolored, and optimistic architecture. Kingelez, who died in 2015, used paper, tape, and glue, and objects like Coke cans, Christmas ornaments, and hypodermic needles, to create fantastic skyscrapers for existing cities, as well as imagined metropolises in miniature. The show runs until Jan. 1, 2019.

Working predominantly in the 1980s and 1990s, Kingelez created an aesthetic that looks like a mélange of Oz, Candy Land, the Wakanda of the recent Black Panther movie, and Wes Anderson’s Grand Budapest Hotel.

While walking through “City Dreams,” the viewer might feel out of time. The color-popping skyscrapers look ready to blast off back to the space age, or to a late 19th-century world fair. The label for a 1988 sculpture reads, “Allemagne An 2000”: Germany in 2000. Another work, completed in 2000, imagines the French city Sète in the year 3009.

The delicate models invite viewers to lean in eagerly and squint at their flamboyant details—much to the chagrin of the on-edge security staff who hover nearby. Bright blue curves in the courtyard of a hospital look like swimming pool lanes; the facade of a bright yellow skyscraper looks like Skee-Ball targets; a building that resembles the hair of Simpsons character Krusty the Clown is a bird, about to take flight.

“I like to think that this is work that rewards both the first glance and the long look,” says MoMA curator Sarah Suzuki in an interview at the museum.

Kingelez used skyscrapers to express his fundamental optimism. ”A city without high-rise buildings is a dead city,” he once said. “A non existent city.” Through his designs, he engaged with geopolitical events and dreamt of a bright future for the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which gained independence from Belgium in 1960. He recreated Kimbembele Ihunga, his home village, as a gleaming cityscape: The side of one building is like the mane of a cartoon unicorn, and a pale pink church suggests the ribs of a whale.

The artist frequently created structures for Kinsasha, where he lived as a young man. One building is surrounded by bright blue panels, intended to look like butterflies, which seem to uplift the structure.