One of India’s first horror comedies has a radical feminist lesson

“Come home soon, I feel scared when I’m alone!”

“Come home soon, I feel scared when I’m alone!”

Typically, that’s the kind of thing that women might say to their husbands or fathers or brothers in India, a nation where 106 rapes occur daily. But in the new horror-comedy Stree, it’s the catchphrase for men in Chanderi, a small town in the northern Indian state of Madhya Pradesh.

The cinematic universe imagined by director Amar Kaushik in Stree, which stars Rajkummar Rao and Shraddha Kapoor, flips India’s patriarchal society on its head. It’s a supernatural world where a scorned witch, Stree, hunts lone men down and abducts them every year during a four-day festival every year. She leaves behind a pile of her victim’s clothes on the floor.

When Stree is around, men aren’t supposed to wander alone—especially late at night and especially not alone. In nervous huddles, men discuss whether dressing in a saree (a nine-yard traditional Indian outfit worn by women) would help them escape the witch’s wrath. The all-knowing Rudra bhaiya (brother), played by the brilliant Pankaj Tripathi, tells them that dressing any differently would be foolish and won’t save them.

In the real world, keeping off the streets past 10pm and traveling in groups is advice that is routinely doled out to Indian woman who spend their lives in constant threat of violence and sexual assault. And they are encouraged to dress modestly because, as politicians would have you believe, wearing jeans is an open call to rapists. But clearly, there’s little sense in that, since heinous criminals don’t even leave children or old women alone.

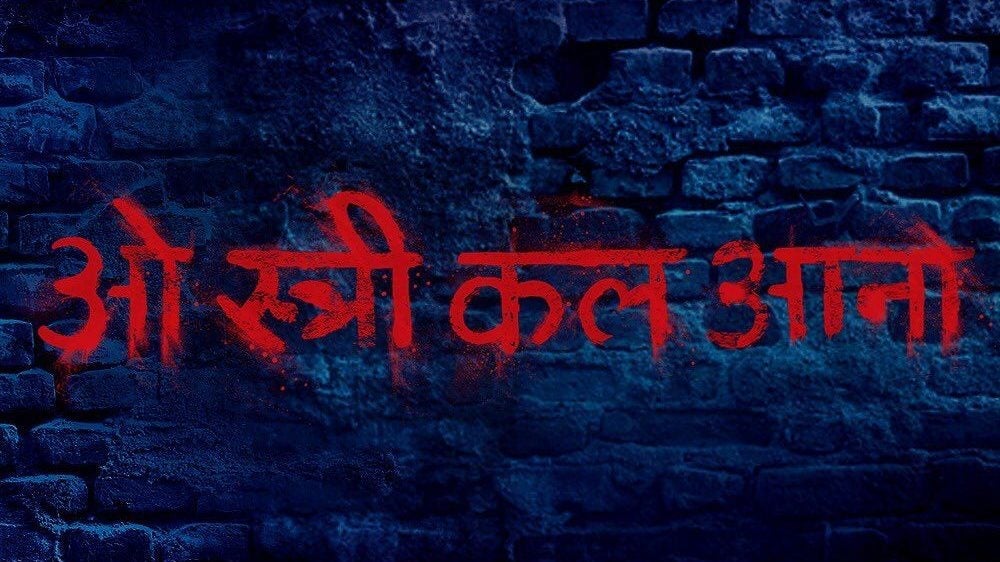

A great quirk of this seductress-ghost is that she doesn’t believe in using force. Every house in the locality paints the words “O Stree, kal aana” (O Stree, come back tomorrow) on their walls and the literate, obedient spirit obliges. Even when abducting her victim, she doesn’t do so without their will. Tripathi’s character, the local scholar, explains: Stree doesn’t force her victims like men do. She sweetly calls out their name three times. If you turn around, that’s consent.

In case you don’t catch all the subtle nuances, there’s an even more obvious feminist narrative underscoring Stree’s own story. The folklore says that Stree, a prostitute, and her lover were ostracized and eventually killed by the oppressive, misogynistic society they lived in when they got married. She’s back to demand the love and respect she never found during her lifetime. She kidnaps men and derobes them out of vengeance, in line with the film’s tagline—Mard ko dard hoga (Man will feel pain).

Though the film runs on more laughs than spooks, the real terror seeps in once you leave the theater—and realize that the four-day trying period for the men of Chanderi is an everyday nightmare for the women of India. Perhaps that’s why the movie surpassed box office expectations by a mile within the first few days and even made it to the coveted Rs100-crore club, an unofficial Bollywood hall of fame separating the most successful movies from the rest.

Eventually, Stree sets the abducted men free and leaves the town and a statue is built in her honor by the townspeople. In real life, women are almost never that lucky. If they are not brutally murdered, they succumb to their injuries days later. And if not that, society stigmatizes them to the point of no return.