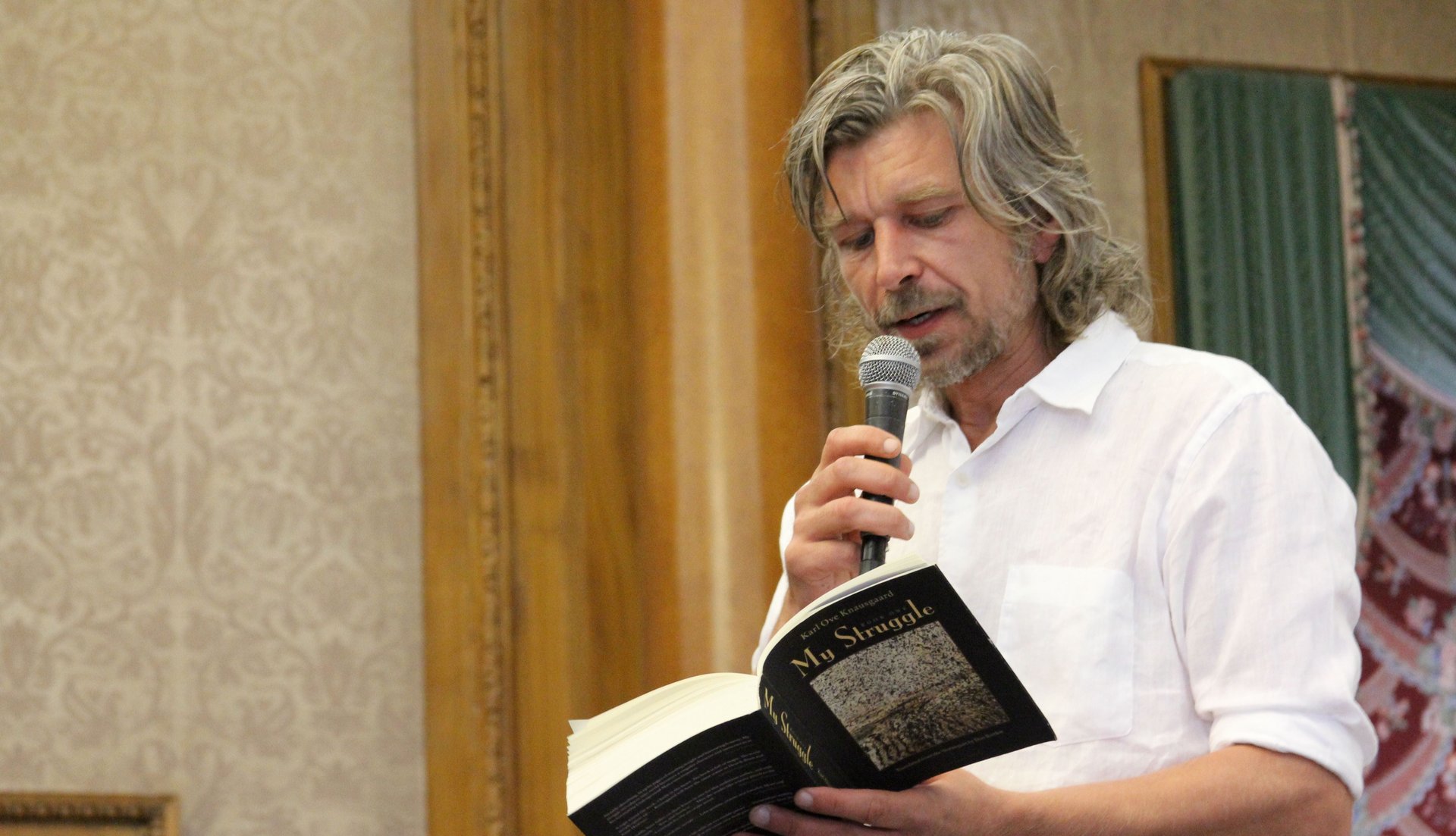

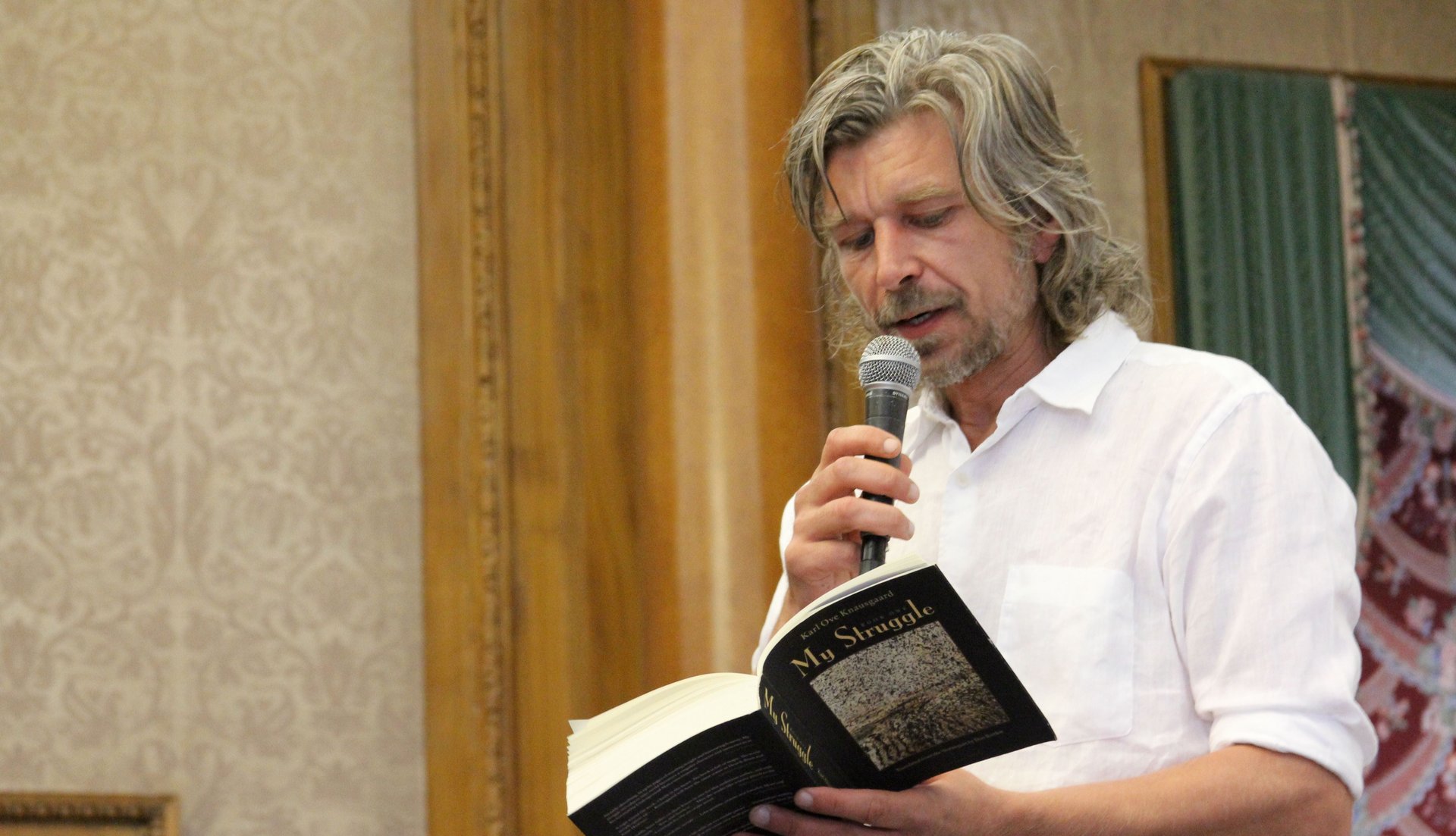

Karl Ove Knausgaard’s surprising secret for curing writer’s block

Novelist Karl Ove Knausgaard doesn’t struggle with writer’s block. Obviously.

Novelist Karl Ove Knausgaard doesn’t struggle with writer’s block. Obviously.

The Norwegian author of the six-book autobiographical series My Struggle has become Norway’s most translated novelist worldwide, inspiring shock and awe in strangers and family alike with his epic expository work that cribs the title of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf. Yet Knausgaard wasn’t always prolific. He used to struggle with writing, most notably when he was most free.

In a recent interview with the New Yorker, the writer reveals that the secret to getting a ton of work done is having a busy life and short deadlines. “It’s strange that, with three small children and limited time, I wrote so many pages a day while, before, when I spent all the time I wanted on writing, and even lived on isolated islands and in remote lighthouses, I hardly wrote anything,” he says.

The series Min Kamp—Norwegian for “my struggle”—was published in Norway between 2009 and 2011. Knausgaard wrote the first two volumes in a single year, three more the following year, and took a six-month break for the final volume, then got it done. The first book took eight months to complete and the fifth only eight weeks. Previously, Knausgaard took six years and five years respectively between books.

At 19, he wrote his first novel very quickly, but it was “crap, unbelievably silly and stupid,” according to Knausgaard. It was rejected by publishers. “When the novel was rejected, I lost belief both in myself and in speed. I started to polish the car instead of driving it—and, obviously, when you polish your car, you don’t get anywhere, no matter how nice the car looks,” Knausgaard tells the New Yorker.

Still, the thrill of writing quickly, losing himself in an endeavor, stayed with Knausgaard even over the years he didn’t write and took all his time polishing the proverbial car. “[S]peed-writing became like reading, a place where I disappeared,” he explains. And he was pleased to rediscover this ability when he wrote the novels that have made him an international literary figure.

Waiting for inspiration

Knausgaard makes a great point. Even if you write something of poor quality but do it quickly, you’re already getting somewhere. Reflecting on writing is fine sometimes, but it doesn’t actually bring you any closer to completing a work, whereas having a draft, even if it’s bad, gives you material to hone.

While writing needn’t be a race, working at a rapid pace is liberating. It takes you to places you can’t conceive of when just thinking. Indeed, writing is the thinking process made manifest. In the act itself, thoughts crystallize. It’s reflection tethered to process, physicality. Putting words down leads you. The writer doesn’t have to decide because the writing does it for you—and later, you can go back and drive the car more deliberately.

Lots of writers, like Knausgaard, find deadlines and limited time extremely inspiring. Forcing yourself to get to work is a major step in accomplishing the goal of working. On the other hand, waiting for inspiration, the perfect moment when your brilliant idea has finally crystallized, is a recipe for, if not disaster, at least for getting nothing done.

As novelist Jessie Greengrass puts it in LitHub, “Having no time is the best time to get writing done.” She allots herself a specific, set time to write every day and finds that she gets much more done this way. “Often, during my two and a half morning hours, I feel that I am trying to wrestle with my conscious mind, to hold it to task when it would prefer to wander, but I can’t wait for inspiration and must rely on the incremental growth of words ground out across a page,” she explains.

Greengrass is a lot more productive now that she only has a couple of hours a day to write, compared to when she was younger and had fewer responsibilities. “Without set hours, without external demands on my time… I would get nothing done at all. I would drift, and wait, and time would pass, and I would feel, increasingly, as though I had failed.”

On “plumber’s block”

While some literary types do believe in writer’s block, at least as many decry it as a myth. The Nobel prize–winning novelist Toni Morrison said in a 1994 interview, “I disavow that term.”

Judy Blume, author of Are You There God? It’s Me Margaret, told Buzzfeed in 2015, “I don’t believe in writer’s block. For me there’s no such thing as writer’s block—don’t even say writer’s block.”

Writing may not always go smoothly, but neither does anything else. “Sometimes, writing is super hard. Just like any other job. Or, if it’s not your job, sometimes it’s hard to do a thing even if it is your hobby,” explained the science fiction writer Patrick Rothfuss, author of the Kingkiller Chronicles, speaking at Comic Con in Seattle this year. “But no plumber ever gets to call in to work, and they’re like ‘Jake, I have plumber’s block,’ you know? What would your boss say?! I have teacher’s block. I have accounting block. They would say ‘You are fired! You have problems and you are fired. Get your ass in here and plumb some stuff, Jerry!'”

The late Nora Ephron also disavowed writer’s block. In 1973, before she became a famous filmmaker, when she was a 32-year-old star reporter, she told Michael Lasky, “I am never completely cold. I don’t have writer’s block, really. I do have times when I can’t get the lead and that is the only part of the story that I have serious trouble with… But as for being cold—as a newspaper reporter you learn that no one tolerates you if you are cold; it’s one thing you are not allowed to be. It’s not professional. You have to turn the story in.”

The life-changing magic of getting it done

Ephron, like Knausgaard, relied on deadlines to make herself write. And within this restriction, she was free.

Making yourself buckle down and do things is a fantastic way to get things done. It’s the simplest life hack we hate. Doing doesn’t have to feel good in the moment, though it might.

Writing, like exercise, work, and household chores, isn’t always fun. Wrestling with yourself and your thoughts can be a pain and is often disappointing. The space between the theoretical great work you might create if all conditions were perfect and the actual stuff that comes out when you sit down and type is enormous.

Writer’s block, to the extent it exists, stems from a suspicion that your work may not be great, and a reluctance to face that fact. When you’re always polishing the car, as Knausgaard puts it, you never go anywhere. That means you won’t get in an accident or discover that the places in your imagination weren’t that great in reality, but it also means you can never find out what’s truly possible, what you are actually capable of accomplishing.

The desire to be great gets in the way of greatness if you can’t manage perfectionism. Sure it would be wonderful to only pen pearls of wisdom. But writing something beats producing nothing. And it’s the only way to get the requisite practice that makes it possible to maybe one day actually write something amazing.

Believe me. I write a lot and on many topics, from octopuses and cockroaches to psychology, politics, language, and law. Before every story, I am briefly filled with dread. It’s never obvious how notions will become a post. So I don’t consciously question the process. Instead, I ignore my doubts, fears, concerns, and desires, and deal with the puzzle.

Solving the puzzle involves reading and writing. Bit by bit, I make the pieces fit until there is a story where before there was just an assignment or an idea. And the more stories I write, the easier it becomes to write more.

Sure, I would love for every post to be a work of genius, yet I never expect that to happen and try to be satisfied with the fact that I’m practicing, working with what I have. The constraints of word counts and deadlines end up being freeing and I can live with the fact that I make “termite art.”

Artist Manny Farber coined that phrase, as Quartz’s Jenni Avins recently explained. He concentrated on little things, preferring “buglike immersion in a small area” over attempts to be huge, like a white elephant. And after every small creation, he moved on to the next thing, detached, “forgetting this accomplishment as soon as it has been passed,” as he explained it.

Farber wasn’t aiming for grandeur. But he accomplished just that in the grand scheme, as evidenced by a new exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles: One Day at a Time: Manny Farber and Termite Art.

Like Knausgaard, Farber was more interested in driving the car than polishing it. Yet both the artist and the writer, and many other greats like them, have managed to wow the world with their work by focusing in this way. While that’s no guarantee that the rest of us will reach the same dizzying heights, they certainly are inspiring examples of getting the job done.