Zozo’s promise of fast, cheap custom clothes with its Zozosuit looks like a bust

Earlier this year, Yusaku Maezawa made the wildly ambitious announcement that Zozo, his company’s private-label clothing line, had developed a tech-enabled system that allowed it to make and deliver custom-made clothes in two weeks to customers in 72 countries.

Earlier this year, Yusaku Maezawa made the wildly ambitious announcement that Zozo, his company’s private-label clothing line, had developed a tech-enabled system that allowed it to make and deliver custom-made clothes in two weeks to customers in 72 countries.

“The time where people adapt to clothing is over,” said Maezawa, CEO and founder of Zozo Group, which runs Japan’s largest fashion e-commerce platform, Zozotown. “This is the new era, where clothes adapt to people.”

But that new era is not going quite as promised.

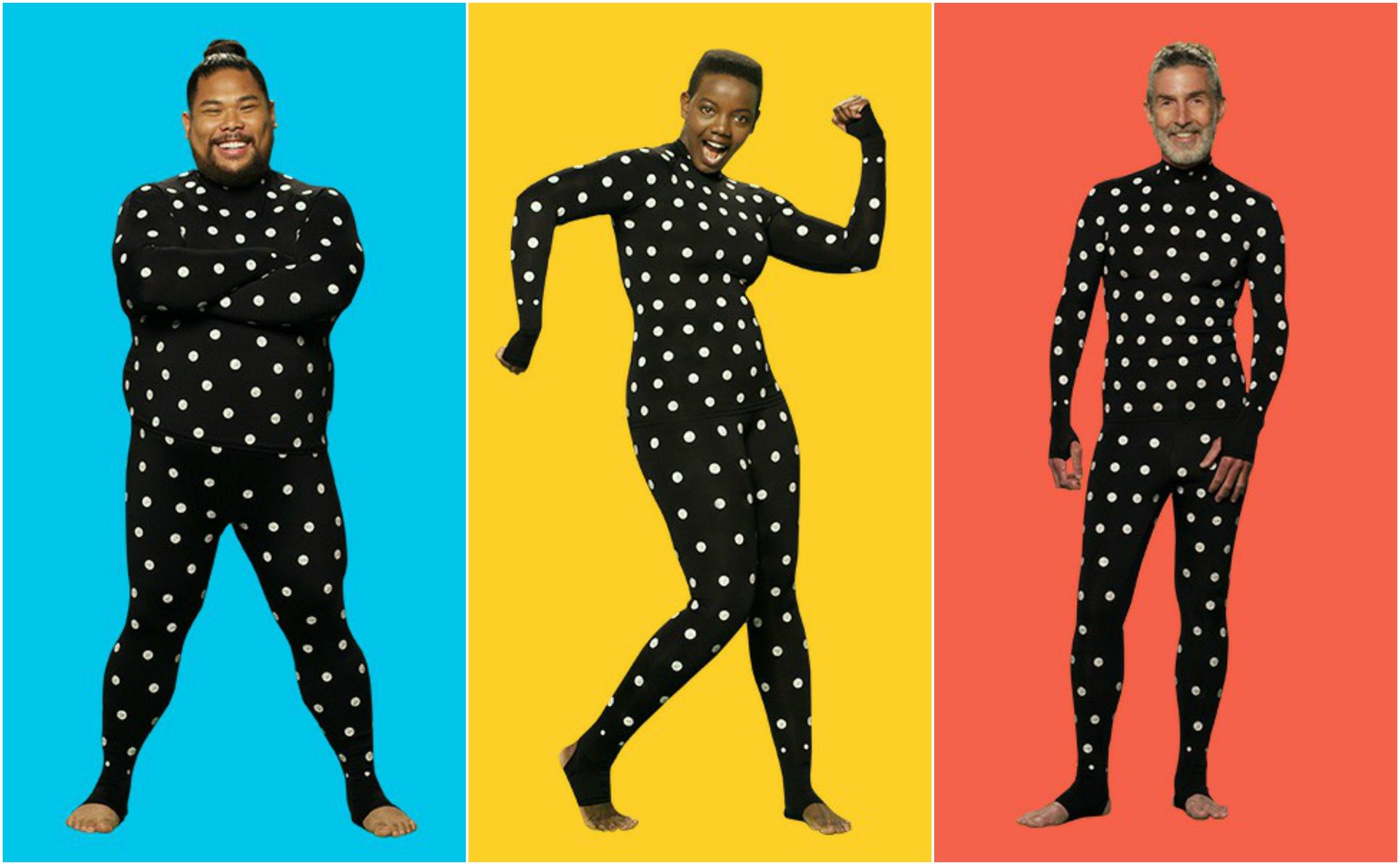

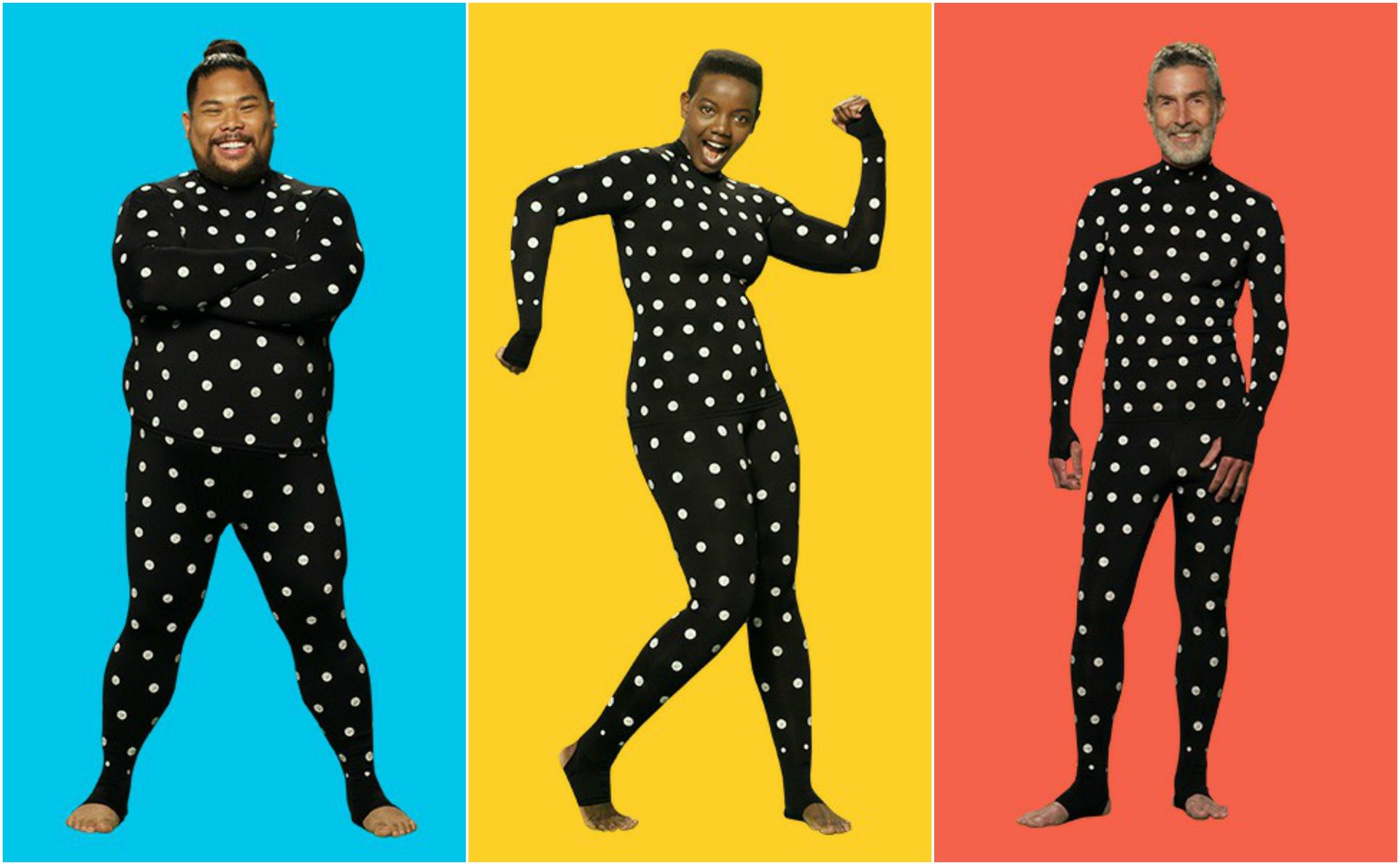

Maezawa was referring to his company’s big idea for making cheap, fast custom clothes: the Zozosuit. It’s basically a spandex bodysuit covered in polka dots, which promises a perfect measurement of your body’s dimensions and contours. The Zozo app, using your phone’s camera, measures the distances between the dots to create a three-dimensional model of the wearer’s body. In theory, it gives Zozo all the information it needs to make custom clothes that fit better than anything you could buy off the rack.

The company said it spent seven years developing the clothes-sizing process, and that it would use automation in its production line to produce the clothes quickly and inexpensively—just two weeks for custom jeans and t-shirts, for example.

But in The Economist’s 1843 magazine, and then in Gizmodo, writers have described their unsatisfying experiences, to put it gently, with their custom orders from Zozo.

“Zozo’s marketing had led me to expect perfection,” wrote Charlie Wells in 1843. “What I ended up with were the kind of clothes you might buy in a hurry from Uniqlo or Gap if you go on holiday and your suitcase gets lost in transit.”

“Everything fit wrong,” Ryan F. Mandelbaum said at Gizmodo. “The jeans wouldn’t stay up without a belt. The button-down shirt’s extra material hung over the pants and could probably have fit a person twice my size—even the t-shirt fit like some shitty promo swag launched out of a cannon at a baseball game. The quality felt no better than a shirt from Old Navy, which probably would have fit me better.” The clothes also took three months, rather than two weeks, to show up.

On Twitter, people have also voiced complaints about the fit of the clothing:

Mandelbaum said he felt “duped,” and Wells “used.” Both suggested Zozo had ulterior motives with its Zozosuit, a charge Zozo is now having to defend against.

One accusation was that the Zozosuit’s expansion around the world was a well-timed publicity stunt, coming at a moment when the company’s profits were down, thanks largely to the costs it had racked up with the Zozosuit in its home market of Japan. The announcement had gotten coverage from numerous publications, including Quartz, and the company has since said they’re discontinuing the suit in Japan.

Masahiro Ito, a director and board member at Zozo Group, said the Zozosuit is not a gimmick: “Globally, the suit will continue to help us serve the diverse needs of shoppers worldwide and allow us to improve the customer’s ultimate experience with their apparel,” he said in an emailed statement.

He explains that, from the company’s point of view, it no longer needs the Zozosuit in Japan, where it has worked with and gathered data from millions of customers and feels confident about its ability “to provide a great fit within that market.” He added that Zozo only views the suit as a body measuring technology, and that it had always planned to keep updating its methods for providing the best fit. (It has hinted previously that it may expand to other categories, too, such as overcoats, bras, and shoes.)

The writers also expressed some discomfort with how Zozo would use their data. Ito said the company only ever collects data to improve the fit of the clothes, and nothing else. ”We don’t sell ads or let any third party access the data we have,” he said. “It’s quite different from the data collection of Facebook, Google, or other companies that consumers are concerned with—their business models require that they literally profit directly from the data they acquire. Ours simply doesn’t. Any data collection we do ultimately serves our customers in the form of better fitting clothes and easier to use body measurement technology.”

The company is admitting, however, that it was too ambitious in saying it could ship to 72 countries within two weeks right from launch. Zozo’s supply chain wasn’t able to handle the complicated logistics. It has fixed some of the major issues, the company said, and is doing everything to make sure people are able to get their clothes within six weeks now.

Demand for the free Zozosuits, meanwhile, has been high, and costly for Zozo. “We have given out millions of ZOZOSUITs at our own expense, which has been an immense investment,” Ito said. “If all we wanted was publicity, advertising would arguably have been more efficient and less expensive.”

Zozo’s mistake appears to be promising too much, too soon. Now it has the added challenge of convincing shoppers that it can deliver on its promises in the future.