An artist’s $100 million suit against museums that rejected his work

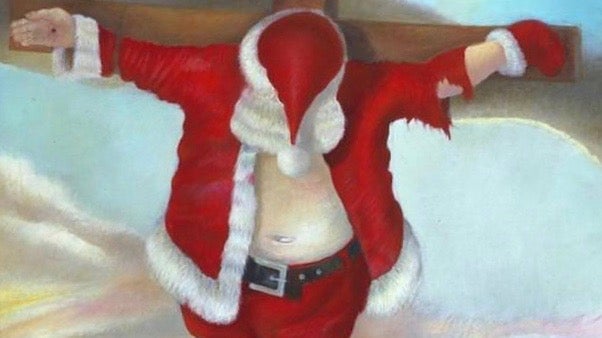

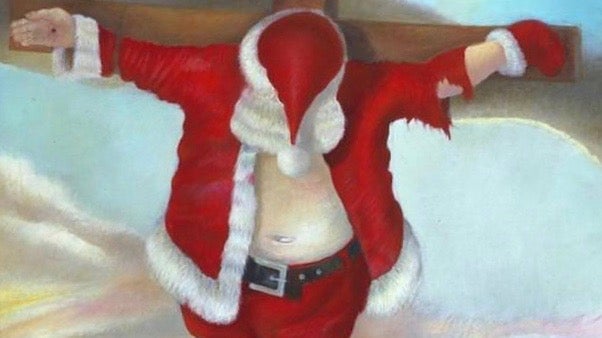

The art business is notoriously hard to break into and extremely difficult to make a name in. Some artists get depressed and blame themselves. Others curse critics. The painter Robert Cenedella, subject of a 2016 film called Art Bastard, which characterizes him as an “outsider” and the “anti-Andy Warhol,” thinks there’s something much bigger at play.

The art business is notoriously hard to break into and extremely difficult to make a name in. Some artists get depressed and blame themselves. Others curse critics. The painter Robert Cenedella, subject of a 2016 film called Art Bastard, which characterizes him as an “outsider” and the “anti-Andy Warhol,” thinks there’s something much bigger at play.

Cenedella believes there’s a conspiracy among major museums, galleries, collectors, and auction houses to keep demand and prices high for a chosen few contemporary artists, and in February he filed a class action lawsuit claiming a violation of antitrust law. The artist targeted five prominent New York museums that have rejected his work—the Metropolitan, Guggenheim, Museum of Modern art, New Museum, and Whitney—arguing that they are part of a cabal to eliminate competition in the art market. On Dec. 19, a New York federal court rejected Cenedella’s claim but left the door open for more litigation.

In his 32-page opinion (paywall), which was almost as harsh as a critic’s unfavorable assessment of an artwork, judge John Koeltl explains that he’s dismissing Cenedella’s case because the artist hasn’t shown there’s an actual controversy that can be resolved with a lawsuit. “Although the plaintiff assures the court that his work is of a quality that would be shown in the defendant museums if not for the alleged conspiracy, this subjective boast alone cannot substantiate the plaintiff’s claim that enjoining the alleged conspiracy would lead the defendants to begin purchasing his work,” Koeltl writes.

Cenedella argued that by conspiring to keep demand high for just a few artists, art-market insiders have depressed prices and desire for work by those who aren’t chosen. He didn’t say his paintings would necessarily hang in New York’s great museums, but that they could, that they were good enough, and that demand for his work was lower because the defendants were stifling competition.

The court concluded that the claims were too tenuous and that any injury Cenedella might have suffered was indirect. Koeltl called Cenedella’s arguments “highly speculative” and that it would be impossible to determine what the works were really worth. Art’s value is subjective and there was no way for the judge to say whether museum staff would choose his painting over a Warhol if there was no alleged conspiracy, given the vagaries of “public taste, the interest of purchasers, and the opinions of critics and academics.”

Yet, Cenedella’s claim is not dead yet. The case was dismissed without prejudice, which means he can still try to revive the suit by filing again with the missing facts filled in. If Cenedella can do more than just assert that there’s a conspiracy and show the insiders had a motive to conspire, backed by actual evidence, that might allow for some legal remedy to be crafted, and he might just get his suit to trial.

What’s certain is Cenedella’s move to sue was clever. His works may not end up hanging in the great museums of New York, but by filing the case, he’s getting more attention and that is what artists need to succeed.