The beauty industry feeds on anxiety. Now it’s selling anti-anxiety products

Beauty brands are getting into the stress business. Instead of just making you look pretty and smell nice, perfumes, makeup, face oils, and cleansers are now packaged with a new set of claims: that they’ll boost your mood and relieve your stress.

Beauty brands are getting into the stress business. Instead of just making you look pretty and smell nice, perfumes, makeup, face oils, and cleansers are now packaged with a new set of claims: that they’ll boost your mood and relieve your stress.

The clean beauty brand Osea, for example, sells a body oil billed as a stress-regulator by “stimulating positivity and wellbeing in the mind and body,” while Ritual’s relaxing serum promises to “relieve stress or tiredness.” Dermatologica sells a “stress relief treatment oil” that will “soothe the psyche” and most CBD-containing beauty products (from chapsticks to lotions) purportedly double as stress relievers thanks to the ingredient’s reported anxiety-relieving properties.

While CBD is relatively new on the scene, aromatherapy is an older concept. Like many things formerly relegated to health food aisles, it has been embraced by the wellness industry, whose self-care products—tonics, oils, and fragrances, and many skincare products—can also be found at a department store or Sephora. Many of these products contain fragrant essential oils, and include instructions on how to use them in a sort of relaxation ritual—”massage into the temples” for example, or “take a few deep breaths while massaging product into the neck.” It’s worth noting, however, that the clinical evidence supporting aromatherapy is thin. In particular, a 2014 meta-analysis notes that evidence around the benefits of aromatherapy remains limited. (A recent preclinical study on mice did highlight lavender as an effective aid for stress reduction.)

It’s not surprising that the beauty industry wants to tap into our stress—it’s a big business. According to the American Psychological Association, stress levels in the US saw their first significant uptick in a decade in 2017. Eight in 10 US adults reported feeling stressed during their day, with 44% reporting that their stress levels had increased over the past five years. A recent Buzzfeed story on “millennial burnout” recently went viral, and triggered an outpouring of shared angst about overwork and “errand paralysis.“

What’s more, it’s a natural transition: stress relief goes hand in hand with the self-care, a movement that beauty brands have embraced with gusto. Recent sales of skincare have surpassed (PDF) color cosmetics and makeup, and brands have encouraged customers to replace their regular old routines with more intimate beauty “rituals” that create an emotional association with the brand.

That said, there’s something a little rich about the beauty industry offering cures for our anxiety—given its own complicity in generating it. The cosmetic industry has always relied upon creating pressure to meet a beauty standard that it sets (with actors and supermodels as spokespeople) then airbrushes to poreless perfection.

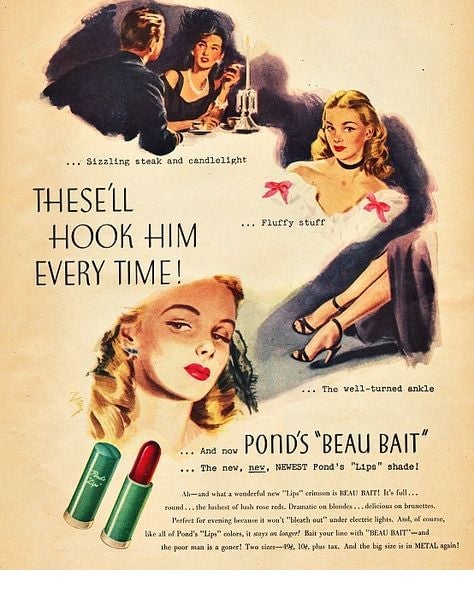

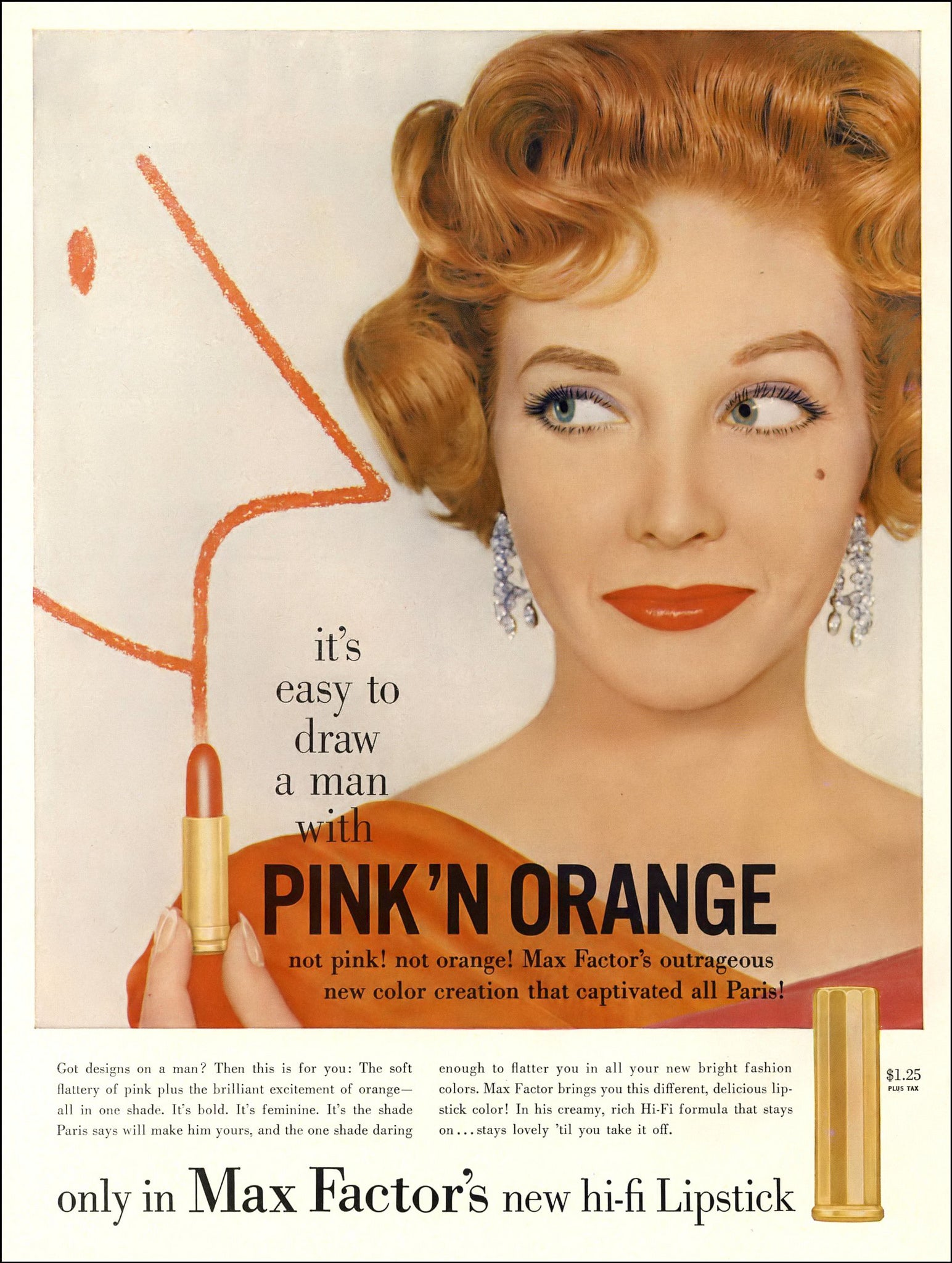

Big Beauty has a long history of getting inside of peoples’ heads. The beauty industry wouldn’t be the behemoth it is today if it hadn’t created a culture where buying and using beauty products feels compulsory. Throughout most of the 20th century, beauty giants ran ads that equated beauty—achieved via a red lipstick, porcelain skin, or long, dark lashes—with success and happiness.

An iconic example is Clairol’s “blondes have more fun” campaign: The company ran a series of the commercials in the 1960s in which young brunette women see their lives infinitely improved—through marriage proposals, improved tennis skills, romantic park romps—after lightening their hair.

In the early 2000s, the industry started marketing self-confidence to women—but again, that confidence was achieved by using its products. It was around that time P&G cosmetic brand Olay launched its iconic “love the skin you’re in” slogan. While this new, confidence-boosting narrative of cosmetics seemed to indicate a shift away from patriarchal beauty standards, the language was still doublespeak: The best way to love your skin, it suggested, was to banish its wrinkles and conceal its blemishes. Less than a decade later, P&G—which owned Covergirl at the time—funded a study asserting that makeup boosts a woman’s attractiveness, which can make her seem more likable and competent in the workplace.

Today, the billion-dollar skincare machine has changed its language, but not its fundamental stance. It still peddles creams, oils, and face masks, but instead of explicitly saying these products will help a woman catch or keep a man, the marketing suggests that she buy them to keep her skin looking healthy, hydrated, and Instagrammable, or to care for herself. Still, the subtext is often the ultimately futile suggestion that these products will keep visible aging at bay. Indeed, it seems that protecting youth is beauty’s new mission—a new wrinkle that doesn’t replace so much as adds to the pressure of looking pretty.

If just reading all this is stressing you out, you might try rubbing some balm on your temples. But while you let its soothing fragrance wash over you, it’s worth keeping in mind that Big Beauty had a hand in manufacturing it.