The body-positive skincare trend is driven by women’s fear of aging

“Revlon Unveils New Age-Defying Monster Makeup.” The headline, in the Halloween edition of the satirical newspaper the Onion this week, was funny, but it tapped into something very real. Color cosmetics (lipsticks, eyeshadows, mascara, and other makeup) are losing their supremacy in the beauty industry, and skincare (lotions and moisturizers, serums, cleansers, toners, masks, and more) has seen monster growth.

“Revlon Unveils New Age-Defying Monster Makeup.” The headline, in the Halloween edition of the satirical newspaper the Onion this week, was funny, but it tapped into something very real. Color cosmetics (lipsticks, eyeshadows, mascara, and other makeup) are losing their supremacy in the beauty industry, and skincare (lotions and moisturizers, serums, cleansers, toners, masks, and more) has seen monster growth.

Driving that growth is not a simple desire to care for skin, but a more complex compulsion to defy age. As Chelsea Summers wrote in her widely shared essay Medium, “Aging Ghosts in the Skincare Machine,” “No matter how low you turn the volume, the specter of aging wails, open-mouthed and horrified, at the core of skincare.”

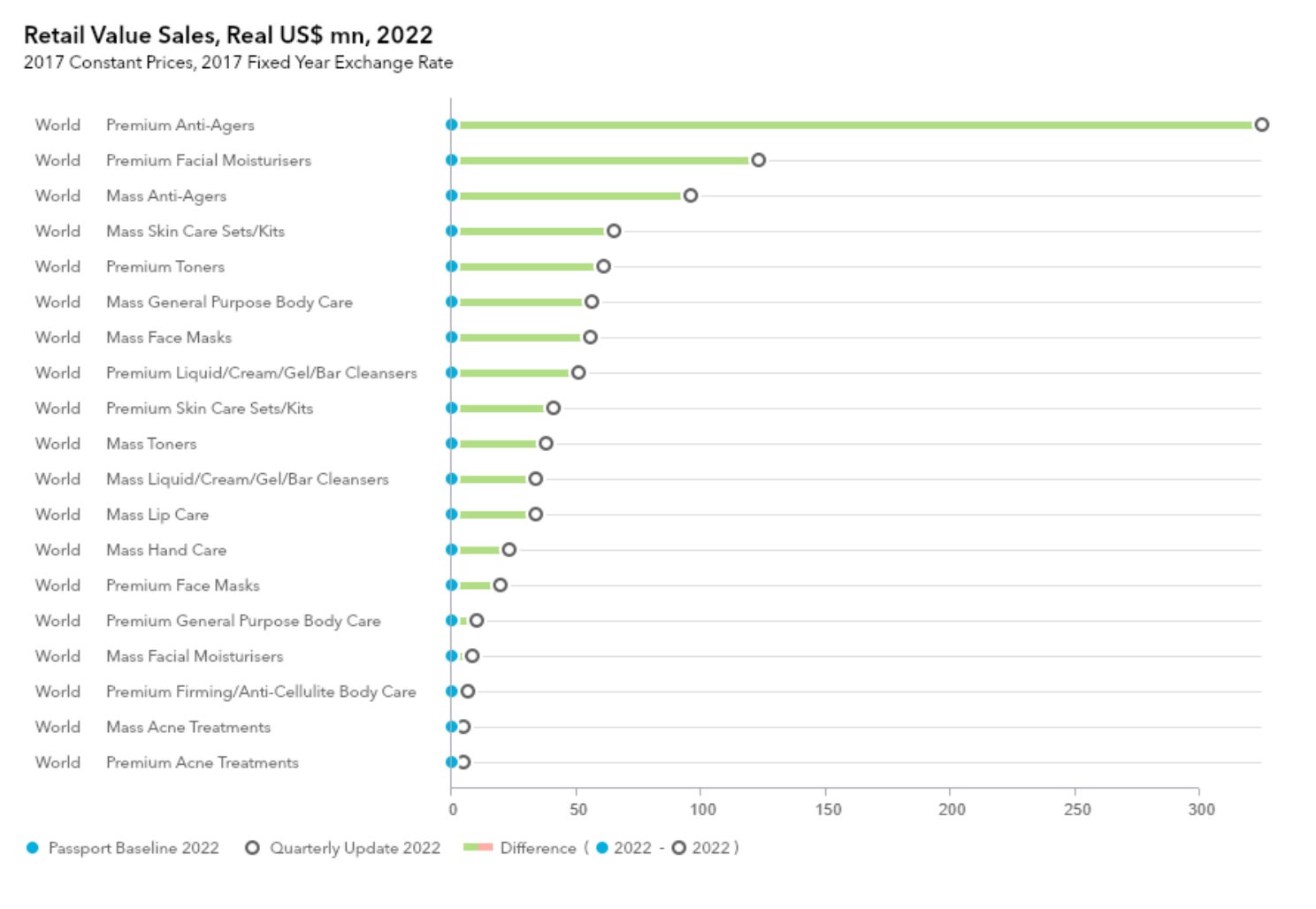

A report on the global cosmetics market by the research firm Euromonitor released in August (PDF) found that skincare experienced the strongest growth globally against all other cosmetics categories, a spot previously dominated by color cosmetics. And when it comes to retail value sales, skincare is dominated by anti-aging products, led by “premium anti-agers.”

Skincare is the key to growth for big beauty

This week’s quarterly earnings statements from the beauty giants L’Oréal and Estée Lauder (two of seven conglomerates that dominate the entire global beauty market) confirmed again that skincare is the industry’s brightest spot. What L’Oréal CEO Jean-Paul Agon described as “a robust growth in skincare” on the company’s earnings call led to its highest quarterly growth rate in a decade.

L’Oréal’s “Luxe” (luxury products) and “Active Cosmetics” (skincare products) were its fastest-growing divisions. The former (which includes Lancôme, Yves Saint Laurent, Giorgio Armani and Kiehl’s) is underpinned by accelerating growth in skincare, specifically from Lancôme’s Génifique and Absolue anti-aging lines. Meanwhile, Kiehl’s skin products are also selling well, with the report highlighting “an excellent performance from [Kiehl’s] Line-Reducing Concentrate.”

In active cosmetics, the anti-aging creams Minéral 89 and Liftactiv Collagen Specialist were spotlighted as two of the most successful products, and the report credits the sector’s worldwide growth to “consumer aspirations for dermocosmetics.” In its “consumer products” division, the report points to rosy sales of L’Oréal’s Revitalift Filler and Laser—both, you guessed it, anti-aging products.

While Estée Lauder owns more color cosmetic brands than its competitor, it noted that global skincare was one of its top growth drivers. Specifically, it highlighted the luxury skincare brand La Mer for its net sales increases across every region, and its best-selling product: a sheet mask that “visibly plumps and energizes” the skin.

“Skincare” is a code word

In an era where women’s empowerment is good marketing, the language of cosmetics is changing to suggest a pivot to self-care. Marketing departments have replaced combative instructions to “tackle” and “beat” blemishes or “defy” aging with products promising to “renew” and “revitalize” the skin. Amidst this shift, “skincare” has become a code word for a category of products that promise to slow, pause, or reverse aging.

The beauty magazine Allure embraced this doublespeak last year when it declared that it would phase out the term “anti-aging.” Editor-in-chief Michelle Lee wrote that a “celebration of growing into your own skin—wrinkles and all” would be the publication’s new MO. But Allure continues to advertise and review anti-aging products, and Lee herself is constantly dispensing skincare advice via her Instagram, much of which focuses on anti-aging.

This makes sense—it’s Allure’s job to respond to beauty industry trends—but as Amanda Hess points out in the New York Times, the problem with skincare’s polite avoidance of the term “aging” is it treats youth as the default, as “simply natural,” and as a proxy for beauty.

You’re never too young to start worrying about aging

The beauty industry isn’t just selling anti-aging to people with wrinkles. These products will almost always make sure to note that they “are suitable for all ages and skin types.” Why create a niche market, right?

And according to the data firm TABS Analytics’ annual beauty survey, millennials are the heaviest buyers of skincare. The nebulous “dewy” skin is the ideal, bolstered by fresh-faced ingénues and #GlossierGirls on Instagram, and today’s young people are undergoing many more extreme, medically-based anti-aging procedures than ever before. Once reserved for an older clientele in expensive dermatology clinics, a new era of brightly lit, affordably priced, Instagrammable skincare studios has quietly ushered in a customer base of people in their twenties and early thirties seeking botox and fillers, and aiming laser beams at their faces.

Beauty is a business that has always thrived by fostering women’s insecurities. In 2018, companies are using the language of self-care and empowerment to sell products that target women’s fear of aging. Lately, that has proved more profitable than selling shame.