The midrange Manhattan hotel that changed American hospitality

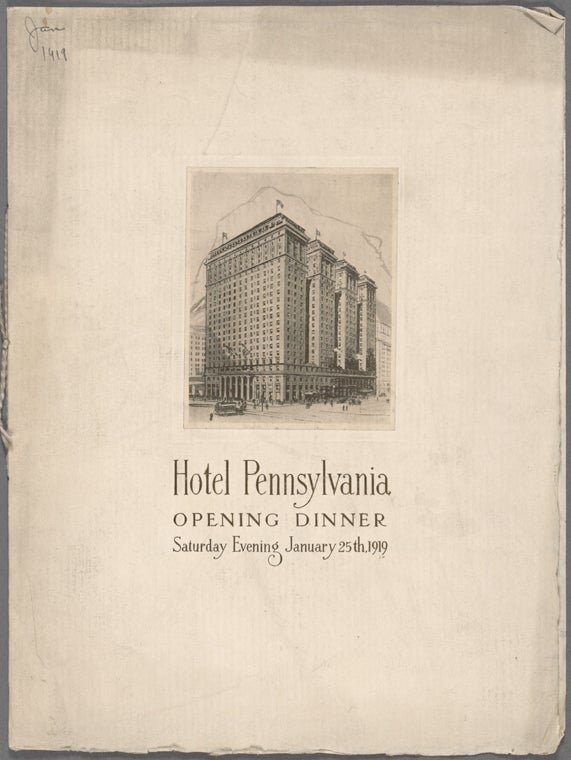

Shame on the Hotel Pennsylvania, and shame on all of us. This midtown Manhattan hotel just had its hundredth birthday, and no one threw a parade down Seventh Avenue. No one handed out free coffee in the lobby or put up bunting. We’re not even sure what day it was—Wikipedia and the New York Times say Jan. 25, but an employee told me it was the 23rd (though he had also heard the 22nd).

Shame on the Hotel Pennsylvania, and shame on all of us. This midtown Manhattan hotel just had its hundredth birthday, and no one threw a parade down Seventh Avenue. No one handed out free coffee in the lobby or put up bunting. We’re not even sure what day it was—Wikipedia and the New York Times say Jan. 25, but an employee told me it was the 23rd (though he had also heard the 22nd).

But make no mistake: This relatively modest hotel most well-known recently for hosting the contestants in the Westminster Dog Show was the most important hotel of the twentieth century. It may not be as famous or fancy, but its innovations made it more significant than the Waldorf-Astoria, the Plaza, the Flamingo, the Watergate, the Ritz in Paris, the King David in Jerusalem, or any other hotel anywhere else in the world.

The hotel’s stacked plumbing systems, slogans such as “the guest is always right,” ensuite bathrooms, and countless other innovations and efficiencies have lived on in American hotel culture for a century. Sitting at 34th Street and Seventh Avenue, it was once the neighbor of the old Penn Station, the architectural marvel whose destruction was a New York City tragedy. The Hotel Pennsylvania still stands, but for all its historical importance, it might as well have been erased.

When it opened in 1919 in New York City, the Hotel Pennsylvania was owned by the Pennsylvania Railroad Company, but it was run by the Statler chain, which had upended the hotel industry over the previous decade with innovative marketing, design, and labor strategies that brought down costs and prices, putting luxury within reach of the middle class.

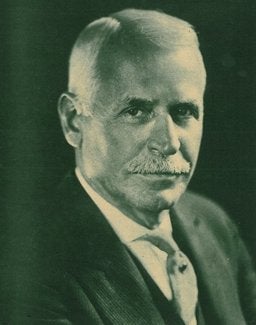

Where previous hotelkeepers and chain operators fought to the top of the industry with bigger, more expensive hotels, Ellsworth Milton (E.M.) Statler changed the game in the mid-range—that all-important swath of the hotel industry that’s once again being reimagined and rebranded today. These days it’s touted as “luxury for all” (or alternatively, seen as “premium mediocre“).

In his time, Statler’s big innovations were bringing touches of luxury to a relatively affordable hotel experience, and bringing the principles of efficiency pioneered by mass manufacturers into the service sector.

Statler already had hotels in Buffalo, Cleveland, Detroit, and St. Louis in 1919. In New York, the greatest hotel city in the world, his ideas reached their largest audience, and changed the way hotels around the world were built and run.

From a glassworks furnace to a hotel empire

Statler grew up poor along the Ohio River, across from Wheeling, West Virginia. He started at the glassworks when he was 9, dumping wheelbarrows of coke into hot furnaces in 12-hour shifts that alternated day and night. At 13 he got his break, a job hopping bells at the McLure House, the big hotel in Wheeling. By 15 he was head bellboy, and from there he kept moving up in the world: He was hired away by a hotel in Akron, then returned to Wheeling where he ran a pool hall, then a bowling alley, then a lunch counter. He moved on a whim to Buffalo to open a restaurant, and built and managed a temporary hotel that slept 2,200 people for the Buffalo World’s Fair of 1901—the one where President McKinley was assassinated.

Statler didn’t make any profits on that hotel, but he tried again at the 1906 St. Louis World’s Fair and did better, despite a tragic accident: The bottom dropped off a coffee urn and spilled twenty gallons of boiling water onto Statler and two others. The coffee boy died, and Statler spent months in the hospital waiting for his scalded legs to heal.

Still, he plowed $200,000 in profits from his single season in St. Louis into his first permanent hotel, which opened in Buffalo in 1907. Others followed: Cleveland (1912, 700 rooms); Detroit (1915, 800 rooms); and St. Louis (1917, 650 rooms). The Hotel Pennsylvania, when it opened in 1919, had 2,200 rooms, the most of any hotel in the world, and it allowed Statler to try his strategies on a grander scale than ever before.

Statler’s genius lay in many areas. He was a master marketer, promoting himself as the figurehead of his company, a folksy, down-to-earth Midwesterner. Decades later the Muppets enshrined him as part of the duo Statler and Waldorf, the two rich jerks heckling from the theater box, but Statler’s persona and public image were never that fancy.

“The guest is always right”

Statler hammered away with two slogans that became intimately connected with him and his company. The first was “a bed and a bath for a dollar and a half.” It noted the relatively cheap price of a room, and also his policy of building hotels with a bathroom attached to every single bedroom. He was the first to do it, saving guests from chamber pots and shared toilets down the hall with grimy roller towels pulled on an endless loop. Private bathrooms were especially appealing to traveling women and children.

His more famous slogan, though, was “The guest is always right.” Statler seems to have been inspired by the motto of European hotelier Cesar Ritz, “Le client n’a jamais tort” (the customer is never wrong), and he used it frequently in advertising and publicity. Around the same time, some department stores changed the phrase slightly to “the customer is always right.” The phrase doesn’t really mean what it said (it never has). But it did set up a protocol for dealing with customers: Statler company policy did not allow the lowest level workers to deny guests’ requests. Instead it directed them to refer unreasonable requests to managers, who could say no. Statler occasionally expressed regret at the license his slogan seemed to give for guests’ bad behavior, but he never repudiated it.

Behind the slogans, Statler’s real goal was to standardize and decrease interactions between guests and workers as much as possible. This saved on labor costs, especially at the huge scale on which his hotels operated, and allowed for enormous profits.

Like Frederick Winslow Taylor with a steel mill and Henry Ford with the auto plant, Statler thought hard about the work and how it got done, and then found new, more efficient ways to do it. But where Taylor and Ford’s “efficiencies” often meant more control over the pace of manufacturing in order to pressure more work out of people for less money, Statler’s solutions were generally true efficiencies. Because of increased scale and thoughtful design of labor, architecture, and technology, Statler’s employees really could do more work with the same effort in the same amount of time.

Statler ran pipes for ice water through the rooms, saving ice-delivery bellhop labor. He replaced buzzers with telephones, saving bellhops the initial trip to discover what the guest needed. He designed a line of sheets that had one-inch hems on singles and two-inch hems on doubles, so chambermaids never had to refold the wrong sheet.

From the beginning of his career, he’d been using innovative design to cut labor costs. Back in his Wheeling days, he’d even devised a rudimentary vending machine, pioneering full self-service.

He realized that less personal interaction meant greater efficiency. This insight reached its most extreme expression with the Servidor, a device that debuted at the Hotel Pennsylvania in 1919—a box in the center of the hotel door with a small door on either side and a mechanism ensuring that both doors could not be opened at once (like the ones you put urine samples in at doctor’s offices today, but much bigger). You left your unshined shoes or dirty laundry for the bellman, and he returned them there. Some of the doors at the Hotel Pennsylvania still have Servidors in them today, though they haven’t been used for decades and will probably be phased out in upcoming renovations.

For all these technical innovations, Statler recognized the connection between worker and customer, when and where they did meet, as the core of his business. All the designs that decreased service interactions also improved them—Statler recognized the fawning servility of the past era as repulsive to his customers, and eliminated workers’ opportunities to impinge on customers’ space and time, hanging around waiting for a tip.

Statler also tried to standardize the interactions themselves, especially by giving workers rote phrases they could repeat over and over. Elevator operators in the hotel, for example, were expected to say “good morning” (or whatever time of day it was), “floors, please,” “please step to the rear,” and “have you your room key?” every time a guest took a ride.

Statler found, however, that workers were more resistant to standardization than plumbing was. Once, according to Statler’s biographer Rufus Jarman, an elevator operator clearly didn’t recognize his boss in the crowd when he switched off the car lights and announced “[h]old onto your hats, folks; we’re going through a tunnel.” Another time, getting on the elevator dressed for golf in “knickerbockers that barely covered his knobby knees, golf socks that hung in wrinkles upon his spindly shanks and a tam-o’-shanter perched unexpectedly upon his Middle Western American head,” the elevator operator mistook him for a hick and tried to convince him there was an eighteen-hole course on the roof of the hotel.

These work rules may have been more about efficiency—preventing any awkwardness or uncertainty that might lead to delay—but Statler sold them as democracy. Standardization meant that every guest would get the same treatment, no matter how rich or famous. Stock phrases, other work rules, architecture and design were all used to bring good hospitality to a much larger swath of the population, and give it to them as equals without special privilege. Since their beginnings in the early 1800s, hotels had been called “palaces of the people,” but Statler was the first to deliver on that populist ideal.

Worker satisfaction is as vital as guest satisfaction

Most importantly, Statler believed that good service required happy workers. Unlike the steel mills of Frederick Winslow Taylor and the auto plants of Henry Ford, if the work put a frown on the worker’s face, it was a problem for the customer and for the bottom line.

The Statler chain followed welfare capitalism strategies that already permeated paternalistic manufacturing industries—it organized classes and sports leagues after hours, put radios in the locker rooms, and began offering pensions, life insurance, stock options, and paid vacations. It did not, however, countenance corporate policies that would lead to greater hotel worker happiness later in the century—trust in workers’ ability to find their own voice with guests, and good-faith negotiation with their labor unions for still-higher wages and benefits. Perhaps if Statler had lived to see the strike waves of the 1930s, he would have been more accommodating to the Hotel and Restaurant Employees International Union than his successors were; perhaps not.

Statler never tried to keep his ideas to himself in order to maintain his competitive advantage. At hotel management conferences, in the pages of hotel trade journals, in his influence on the hotel school at Cornell University (which he was instrumental in founding), Statler championed bigness and chains, labor-efficient design, and humane treatment of workers.

In 1917, he wrote, “[i]t is our policy to have no ‘business secrets’ which are so sacred that they can’t be discussed with other men in the same line of business” and encouraged his competitors to steal his ideas. And it’s a testament to those ideas that they spread far and wide—so much so that we’ve forgotten where they came from, or that they ever had to be thought up in the first place.