There’s a good reason bonsai growers think of trees as their children

Tending tiny trees isn’t exactly like raising small people, yet bonsai elicit extraordinary emotions from their growers. And the pot-grown minis do have a lot going for them. These small trees are arboreal haiku, horticultural poetry, representing an art form, a philosophy, a tradition, and all of nature itself.

Tending tiny trees isn’t exactly like raising small people, yet bonsai elicit extraordinary emotions from their growers. And the pot-grown minis do have a lot going for them. These small trees are arboreal haiku, horticultural poetry, representing an art form, a philosophy, a tradition, and all of nature itself.

“Bonsai are like our children,” Fuyumi Iimura told the New York Times (paywall). Iimura and her husband Seiji run a fifth-generation bonsai shop in Kawaguchi, a city near Tokyo.

The couple lost seven small trees worth $90,000 to thieves last month, including a 33-inch, four-century-old Shimpaku she has been tending for 25 years. “They are our children who have been living for 400 years. I now feel like our limbs were taken away, and miss them every day,” she said.

The couple is desperate to get their trees back and anxious that the thieves care for them in the interim. After all, care is what makes these small growths so special.

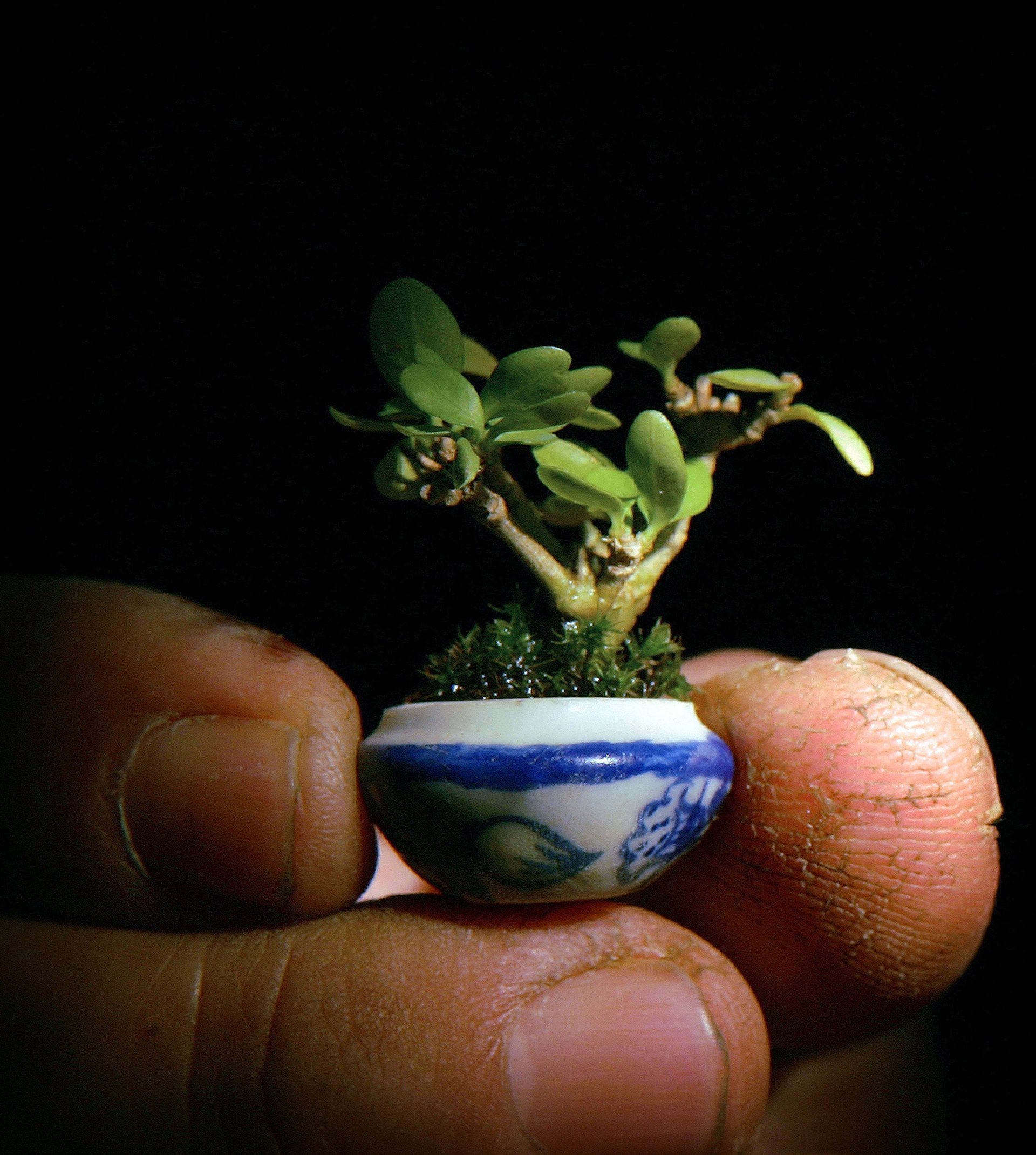

Bonsai are trees or shrubs that grow in a pot and, as a result, are stunted. Their small stature only enhances their elegance and beauty, however. Through careful pruning and wiring, the miniatures are shaped over the years as carefully as a statue, coaxed to grow into tiny representatives of one of the world’s largest living things. They are works of art, tended to and envisioned by humans, made of nature. And in the process of tending, trees and growers bond.

The Iimuras are not the only bonsai aficionados who’ve responded to a theft emotionally. In 1978, Susan Berv of Great Neck, Long Island lost eight trees to a thief suspected to be a bonsai expert and involved in similar crimes in three locales. She told the New York Times (paywall), “[T]hese plants were like children to me. I’ve spent years raising them. Each one has its own personality.”

The love expressed by these cultivators who have lost their bonsai reflects the unique place of these trees in horticultural history and the care the practice demands. Growers don’t just plant a tree in a pot and hope for the best. “Bonsai are a long-term commitment… and most take at least a decade to create,” Julian Velasco, the former curator of the Brooklyn Botanical Garden’s bonsai collection told the AP in 2014. “Some can hardly go a day without some kind of care.”

For the tiny tree lovers, this commitment is part of the pleasure of their practice. It places growers in a long and venerable tradition, rooted in China in the year 200. P’en t’sai or “pot tree” cultivation branched out to Japan around the sixth century, where the practice became known as bonsai, and most likely accompanied Zen Buddhism in its travels from China.

A 1971 history of bonsai (pdf), published by Harvard University, explains the relationship between the Buddhist philosophy and the horticultural practice. “With Zen comes the perfection of the miniature and the associated ideals of self discipline and the emulation of Nature. Potted trees kept small could serve as objects of contemplation as well as decoration.” In other words, bonsai weren’t just cute little guys—these small trees served as an expression of Zen and an object of meditation.

By 1095, bonsai cultivation begins to appear in Japanese literature, where it was deemed “an elegant activity for the samurai.” And in the 19th century, the British traveler Marie Stopes observed in her journals about a visit to the home of the Japanese Count Okuma, “He has also a fine collection of dwarf trees, and I watched one of his gardeners pruning a mighty forest of pines three inches high, growing on a headland jutting out to sea in a porcelain dish.”

The Brooklyn Botanical Garden has one of the most impressive bonsai collections outside Japan, comprising about 350 growths and one white pine bonsai that’s 300 years old. Many Americans first encountered bonsai after World War II—the conflict between the nations subsequently sparked an interest in Japanese culture. The art of the tiny tree soon took hold in the US, and the California Bonsai Society was formed in 1950. The American Bonsai Society was formed in 1967, and it conducts regular conferences for cultivators, teaching the practice as well as featuring bonsai artists.

Theirs is an ancient art form, now practiced all around the world, that follows design principles, just like, say, painting. Yet it demands a profound understanding of, and engagement with, nature. Mother Earth provides the raw materials that an artist will work with. In his 2009 book Mission of Transformation, Robert Stevens writes about the art and science of bonsai cultivation, explaining:

A good bonsai design should be artistically beautiful, with convincing horticultural clues, and should convey a thematic message… The composition components of bonsai are the roots, trunk, branches, foliage pads, crown, container, and accessories (rock, grass, moss, soil etc.). Composition is the placement or arrangement of these components in a unified manner within the work, which results in a creation that is aesthetically pleasing to the eye, and which gives a sense of harmony to the viewer.

Stevens notes that the same principles that apply to art, architecture, and design are important in bonsai. Each grower must consider balance, emphasis, simplicity, contrast, proportion, space, unity, and movement and rhythm. The bonsai artist, however, unlike the painter, works with materials dictated by the nature of the growth. The grower’s job is to study the tree carefully and continually, forming its shape over years so that it conforms to their individual artistic vision and yet appears natural, an idealized miniature representative of a traditional full-sized tree.

In this sense then there is a resemblance between growing bonsai and raising kids. Just as parents use the raw material of nature, education, and their own notions to create children they hope will be more perfect humans, so do bonsai artists attempt to encourage only what is most lovely in their trees and reshape the commonplace—bark, branches—into an extraordinary expression.