What’s behind a stratospheric tourism boom in the tiny European nation of Georgia

If you took a trip to Georgia in the last few years, you probably have a reasonably good idea of why. It might have been the call of the historic capital, Tbilisi, all ramshackle red roofs and fairytale castles, or on the strength of a rumor about the greatest wine scene you’d never heard of. Perhaps you read a honeyed New Yorker story about a seductive, herb-flecked cuisine, or saw the country on travel listicle after travel listicle—the New York Times, the Financial Times (paywall), CNN, National Geographic—and concluded that it was having a moment, and you wanted in. Perhaps it was little more than a cheap flight and a well-timed Instagram post.

If you took a trip to Georgia in the last few years, you probably have a reasonably good idea of why. It might have been the call of the historic capital, Tbilisi, all ramshackle red roofs and fairytale castles, or on the strength of a rumor about the greatest wine scene you’d never heard of. Perhaps you read a honeyed New Yorker story about a seductive, herb-flecked cuisine, or saw the country on travel listicle after travel listicle—the New York Times, the Financial Times (paywall), CNN, National Geographic—and concluded that it was having a moment, and you wanted in. Perhaps it was little more than a cheap flight and a well-timed Instagram post.

But while those things probably didn’t hurt, the real reason Georgian tourism is booming has a lot more to do with geopolitics than it does grapes. The country’s logarithmic growth in visitors, from having fewer than 100,000 tourists annually to 6.5 million in about 20 years, isn’t just the product of it being a very nice place to go. (There are plenty of other very nice places that haven’t experienced anywhere near as much growth.) Instead, it’s the result of huge political change, coupled with a structured, sustained campaign by the country’s government to open Georgia to the world, and take it from a pretty, but mostly unknown, Eastern European backwater to a global tourist hotspot.

For the country’s policymakers, tourism makes perfect sense as a sector to invest in. In a country with an average salary of about $5,000, holiday-makers’ dollars are extremely welcome. In the past two decades, the country’s economy has grown steadily by around 4.5% a year, even amid the turbulence of the global financial crisis, tensions with Russia in 2008, and a tumble in commodity prices. At the same time, poverty has halved from 32.5% in 2006 to 16.3% in 2017. Tourism is a big part of that story, accounting for 7.5% of the country’s GDP growth in 2018.

But Georgia has much higher aspirations. By 2025, according to government documents (pdf), it hopes to attract more tourists from the EU, North America, the Middle East, and Asia; triple tourism revenue to $6.6 billion; and increase the average tourist spend from $328 over five days to $600 over a week. Starting from November, low-cost Ryanair flights from Milan, Bologna, Marseille, and Cologne will send visitors to almost every corner of the country—and help bring in even more visitors with deeper pockets and more cash to flash.

Here’s what’s helped it get this far:

The Rose Revolution opens up doors

In the wake of the Soviet Union, Georgia found itself embroiled in civil war, crime, and corruption—hardly an easy sell to the world’s vacationers. Between 1989 and 1994, the country’s GDP fell by more than half, while annual inflation topped 15,000%. The country’s education and health services lay in tatters, with wages down 90%. Georgia’s economy struggled throughout the knotty process of privatizing many of the country’s formerly state-owned enterprises. At the same time, tensions with Russia seethed—and continue to smolder on.

After 1994, progress was gradual, until 2003, when the Revolution of Roses precipitated presidential and parliamentary elections. Mikheil Saakashvili was elected as the country’s leader, ushering in widespread economic and political reforms, including a pro-Western foreign policy. Significant European and Euro-Atlantic integration followed, as well as a crackdown on corruption and heavy government spending on construction and development. (Saakashvili has since been ousted, and faces multiple charges including abuses of power and embezzlement.)

This change in foreign policy effectively opened Georgia for business.

Speak English, please!

Ranked alongside Hebrew, Farsi, and Thai by the US Foreign Service Institute, the Georgian native tongue is among the world’s more difficult languages for English speakers to master—a major deterrent for Western travelers. Its 33-character alphabet, which has no letters in common with the Roman alphabet, doesn’t help.

For the past decade, however, Georgia’s government has adopted pro-English policies, in an attempt to knock Russian off its perch as the country’s second-most spoken language. In 2011, it lured 1,500 English language speakers to the country to teach in its schools, where English is a mandatory subject. Each teacher received free accommodation with Georgian families and a stipend of about $275 a month. Speaking to the New York Times, minister of education and science Dimitri Shashkini explained that the wider goal was to teach every child in Georgia to speak English.

Georgia now ranks 45th in the world for English proficiency out of 88 countries surveyed by Education First, above Chile and China and below Russia.

A permissive visa strategy

One of the easiest ways to encourage people to travel to your country is to simply open the doors. (When Morocco relaxed its requirements for Chinese travelers in 2016, the North African nation saw a 3,500% year-on-year increase in visa applications from China processed by Ctrip, a Shanghai-based travel agency.)

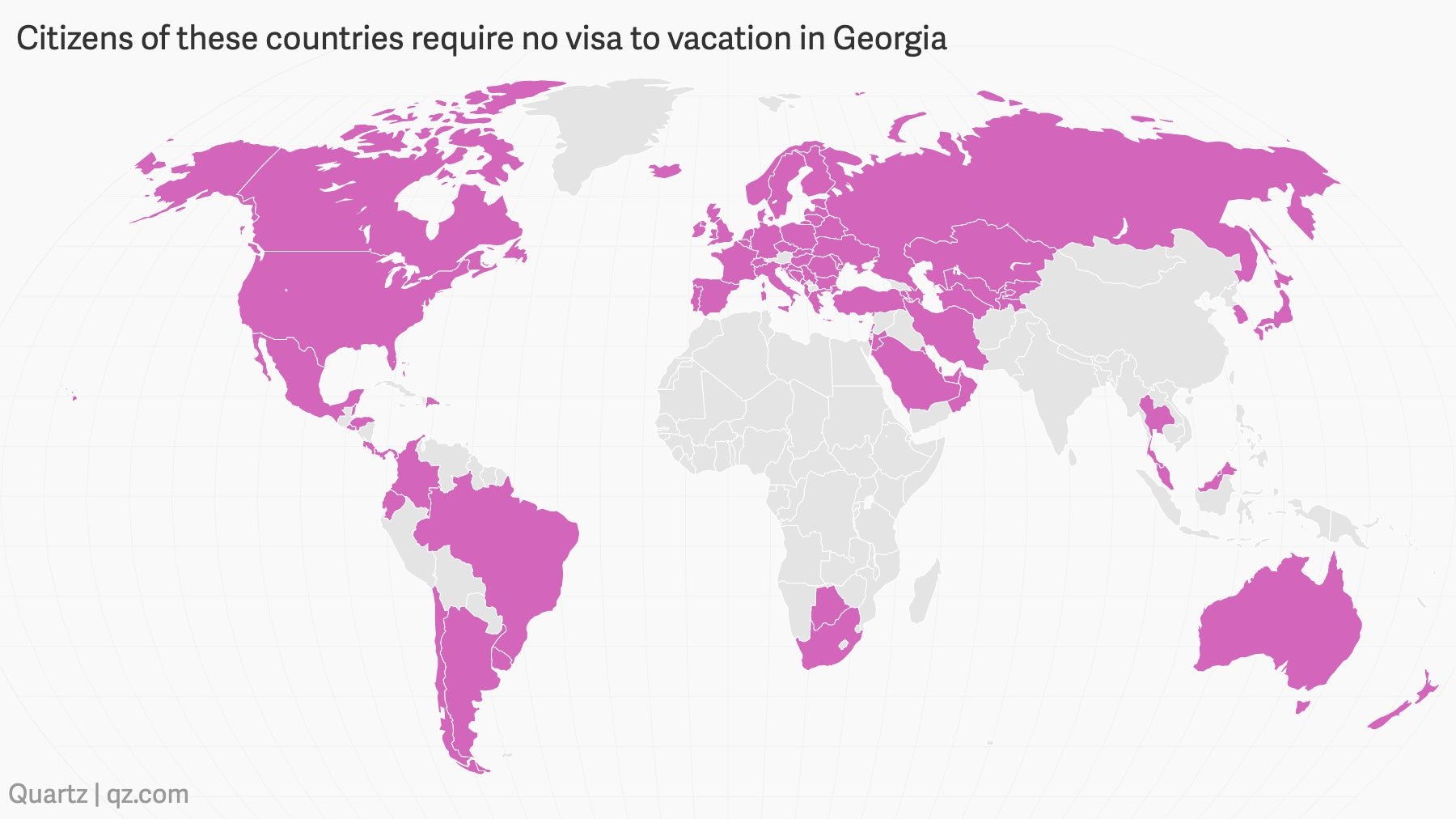

For a month in 2015, Renaissance Capital economist Charles Robertson told the Financial Times (paywall), local passport officials “not only granted you an automatic visa on arrival if you came from a country richer than Georgia, but handed back your passport with the gift of a small bottle of Georgian red wine and sometimes a smile.” The wine is no more, but citizens of nearly 100 countries can now visit Georgia for up to a year without any visa whatsoever.

Enter the World Bank…

Since the early years of independence in the 1990s, the World Bank has put up more than $2.4 billion to support Georgia’s growth—and its nascent tourism industry. This comprised helping it “develop local tourist circuits, establish a system of protected areas, restore cultural assets and local town centers, and finance tourist business development,” according to a 2017 World Bank report (pdf).

In 2015, the bank loaned the country $60 million to improve infrastructure in the Samtskhe-Javakheti and Mtskheta-Mtianeti regions, both of which have striking historical sites and promising ski fields, with the specific goal of increasing tourism. The hope is that this smaller loan will encourage more private investment in the future, in turn encouraging a roaring trade in adventure tourism, skiing, and cultural heritage trips. The two regions had previously been outside of Georgia’s tourism circuit.

Now what?

After experiencing some of the fastest growth in tourism in the world between 2009 and 2016, Georgia has an ambitious plan for the years through to 2025. But a country with around twice as many annual visitors as its permanent population may be taking on more than it can chew, or opening itself up to the risk of over-tourism. Already, visitors report swathes of tourists in the region of Svaneti, with new concrete guesthouses springing up on former farmland to accommodate them. These hotels are said to be at odds with the local cultural and architectural heritage, while their location causes problems with local food supplies.

The country has placed “respecting, enhancing, and protecting Georgia’s natural and cultural heritage” and “creating unique and authentic visitor experiences centered on those assets” at the top of its tourism objectives (pdf). It’s hard to see how it can meet its goals without encountering at least some growing pains.