The North Face’s new fabric is the latest attempt in an endless struggle to stay dry

For as long as there’s been rain and snow, humans have been trying to stay dry.

For as long as there’s been rain and snow, humans have been trying to stay dry.

The newest effort in this centuries-long endeavor comes from The North Face, a company founded on making outerwear for the most extreme conditions on the planet. In September, it unveiled Futurelight, a material it claims will change the future of the outerwear industry. Its revolutionary innovation: “First of its kind breathable, waterproof protection,” The North Face said.

It doesn’t exactly sound like an achievement capable of upending an entire industry, but this combination of qualities is a sort of Holy Grail for outerwear companies. The idea is to keep wearers dry in wet or rainy conditions without getting in the way of the body’s natural ability to regulate its temperature. When we sweat to cool off, what actually cools us is the sweat evaporating off our skin. If your outerwear blocks air from entering and your evaporated sweat from escaping as water vapor, you stay hot and very damp.

Clothing manufacturers have gotten better at blending these traits, leading to innovations such as Gore-Tex, which effectively launched the modern era of performance outerwear in 1976. The North Face believes Futurelight, created with a process called nanospinning, offers the next breakthrough in this long evolution.

From Gore-Tex to guts

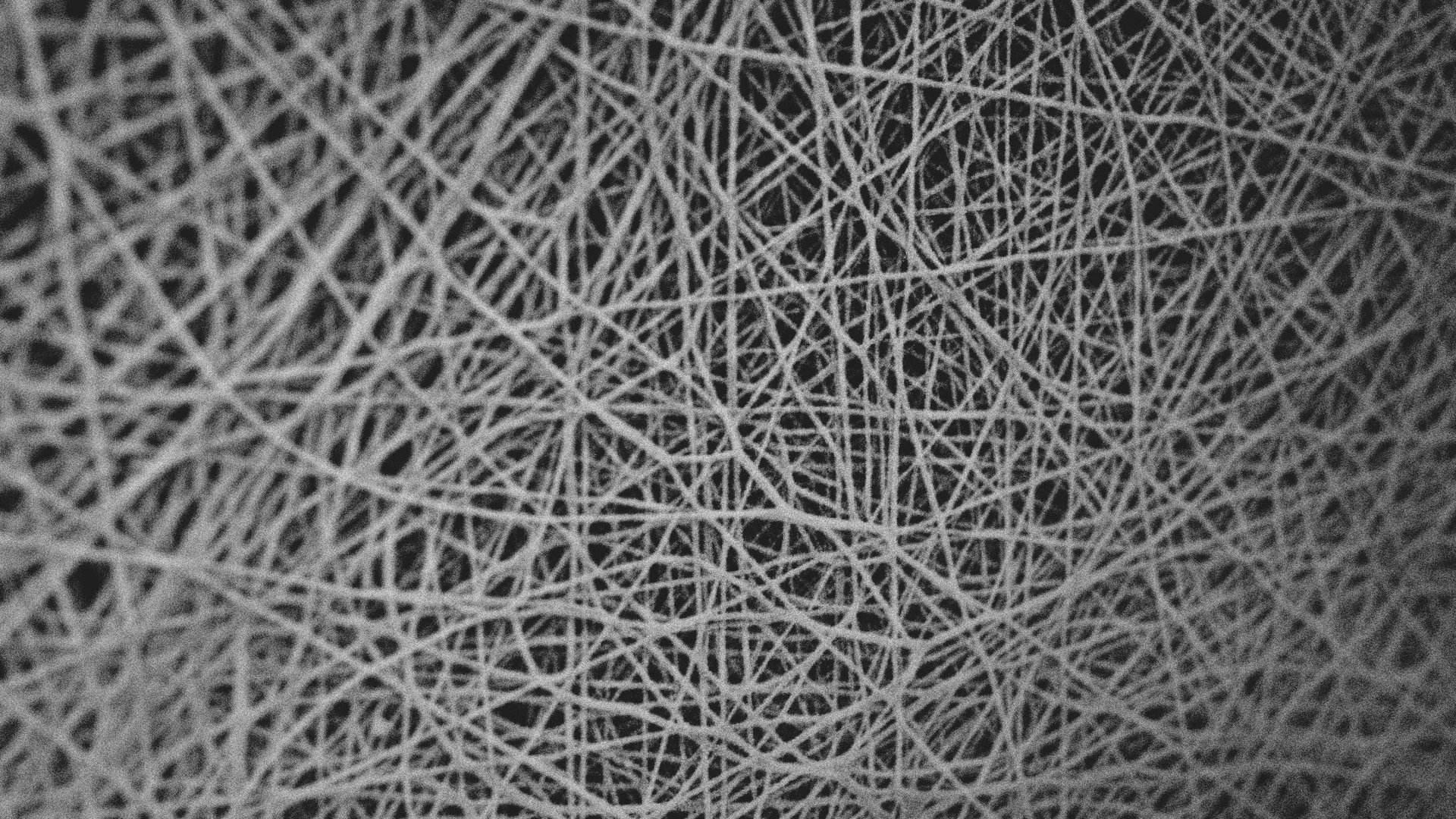

With nanospinning, “you have to imagine there’s thousands of little nozzles that spray a polymer onto the backer of the fabric,” explains Arne Arens, The North Face’s global brand president. He says it creates something akin to a microscopic webbing with holes tiny enough to stop water droplets while allowing air to pass through. The process itself isn’t new and has been used in fields such as electronics and car manufacturing, just not on clothing until recent years.

“The breathability that results makes it completely different than any other outerwear garment the market has ever seen,” he continues. “And that’s what’s so exciting about Futurelight: it’s 100% protected from the elements, whether that’s rain, snow, or wind, but it is also 100% breathable.”

The North Face launched Futurelight with a limited number of products, mostly jackets and pants for serious mountain expeditions. It also has a lighter weight running jacket, called the Flight Jacket. All of them will cost you: The heavy-duty jackets start at $450 and run to $750, while even the Flight Jacket comes in at $280.

The idea was to introduce it on premium items before letting it filter into a wider range of products, including more casual “lifestyle” items and The North Face’s city-focused Urban Exploration line. On an Oct. 25 investor call, Steve Rendle, CEO of The North Face’s parent company, VF Corp., said through spring and fall 2020 Futurelight will start appearing in more products as it begins “to replace current waterproof technologies.”

If The North Face is right that Futurelight works better than anything that’s come before, it would mark the latest achievement in a quest to stay dry that dates back at least hundreds of years. Indigenous peoples in what is today South America were brushing rubber-tree sap, or natural rubber latex, to make items such as rain-proof capes long before Europeans reached their shores.

Centuries later, after rubber’s properties had become a subject of fascination for European scientists, a Scottish chemist named Charles Macintosh got the idea to use it to affix two pieces of cloth together. In 1823, he created the flexible, waterproof fabric that became the foundation for his is Macintosh coats, which give the modern Mac coat its name. It had a few shortcomings though. The puncture holes made when stitching the garment let rain in, while the rubber got hard in the cold and sticky in the heat. It wasn’t until vulcanization appeared in the 1840s, offering a way to stabilize rubber, that these issues were resolved.

Seafarers of various sorts had also devised their own methods of waterproofing. The Inuit peoples of the arctic made parkas from the lightweight, waterproof intestines of whales and seals that could be worn over warm fur layers during hunting and sea voyages. Anna Etageak, an elder from one of these communities, explained the process to the Smithsonian Institution: First they would turn the intestines inside out and clean them. “Scrape it and clean it, maybe all day,” Etageak said. “And they soak it in salt water to make them white, maybe a couple of days or more.” When the strips had dried, they would stitch them together using sinew, which expands when wet, plugging the stitch hole to keep the garment waterproof. The final product was light-weight, breathable, and waterproof.

Europe’s sailors had their own techniques. By the 19th century, they’d discovered that smearing oil on their clothes protected them from wind and rain. It led to the use of treated clothing called oilskins, which typically used linseed oil for their coating. Oilskins could be heavy and smelly, though.

In 1879, Thomas Burberry took a different approach when he introduced gabardine, a fabric so tightly woven water couldn’t easily penetrate it. His coats were light, breathable, and flexible, though not perfectly waterproof: A cotton gabardine caught in a severe downpour will still start to absorb water. Still, they were effective enough that British explorer Ernest Shackleton wore Burberry gabardine, and Burberry would also produce “trench coats” for the British army in World War I.

Other pioneers of waterproofing included companies such as Belstaff and Barbour, which made jackets from waxed cotton. Then vinyl came along, offering a cheap, if not breathable, rain shield.

But the era of modern waterproofing really began when Bob Gore, a chemical engineer working in Delaware, found he could stretch polytetrafluoroethylene—also known as PTFE, the same stuff non-stick Teflon cookwear is based on—into a thin membrane. In 1969, Gore was working for a company that made products such as electrical cables from PTFE. In his research, he yanked a piece of PTFE from both ends but instead of breaking as expected, it stretched, creating a highly porous material. The next year, Gore began filing patents for his expanded PTFE. In 1976, he got his first commercial order for his fabric, Gore-Tex.

Gore-Tex had pores small enough to block a water droplet but large enough for the water molecules in vapor to pass through. It worked remarkably well, and has been used by countless outerwear brands, including The North Face, allowing Gore-Tex to become famous enough to be a punchline on the TV show Seinfeld. It’s not the only effective modern technology. Polartec’s NeoShell, for instance, utilizes a process similar to the one behind Futurelight to create a membrane engineered with “optimal pore size and placement,” the company says, to let heat and sweat dissipate while remaining waterproof. But Gore-Tex remains the gold standard in outerwear today.

Back to the Futurelight

Gore-Tex isn’t used on its own. It’s laminated to other high-performance textiles, often sandwiched between a durable outer material and a liner fabric. It’s the standard form of construction, one Futurelight uses as well. But The North Face’s Arens says Futurelight represents a new advancement.

Arens argues the laminated layers still don’t allow enough air to permeate. The mountaineers the company works with say they need to unzip their jackets all the time to cool down during climbs. It’s not an ideal solution, and if they sweat into their clothes too much, that’s also a problem. Being wet can make them cool too quickly in certain situations, leading to hypothermia.

The average customer probably doesn’t have to deal with these conditions. The North Face says its athletes climbed, skied, snowboarded, and ran in temperatures ranging from -50 degrees F to 60 degrees F in their testing of Futurelight, which spanned more than 400 continuous days. But you may have experienced something similar if you’ve been skiing. You sweat during the exertion of going down the hill, and become cold as all the sweat rapidly cools you on the chair lift back to the top.

Jacket makers have come up with different solutions, such as ventilating zips in the armpits so you don’t sweat like crazy. Futurelight’s ambition is to eliminate the problem entirely, keeping you warm and dry while remaining breathable enough to let you keep your jacket on without overheating. According to Arens, nanospinning lets Futurelight get closer to this ideal than any previous technology.

The first thing I noticed wearing the Futurelight Flight Jacket I borrowed from the company was the breeze. The jacket is a thin, soft shell designed for activities such as running rather than mountain climbing. I deliberately chose to wear it in warm, humid weather. It felt more like wearing a shirt than a jacket. I could feel the air penetrating it easily. A light rain rolled right off it, too, but I know it’s designed to withstand much more than that, so I ran a faucet and held it under. The water flowed off. Even after about 30 seconds, I didn’t notice any moisture on the inside.

I didn’t do any intense activity in the jacket (I generally do my exercising in a gym, where the climate is controlled for me). But reviews of Futurelight products by Gear Patrol and Wired that involved skiing, running, and biking were positive. They didn’t quite hail it as a revolution, but both said it works. It also drapes nicely and feels comfortable because of how soft the material is.

Maybe the most interesting thing about Futurelight is that its nanospinning process could apply to any garment, even a t-shirt, says Steve Lesnard, The North Face’s global vice president of marketing. That versatility will be key to The North Face’s plan to expand it to other products in its big push behind the technology.

On the Oct. 25 investor call, Rendle gave the first insight into Futurelight’s sales. A month into its launch, sell-through—meaning the share sold of the amount distributed—is ahead of expectations, he said. The company is continuing with its previously announced plan to invest an extra $20 million focused mostly on marketing Futurelight. It believes the technology has an opportunity to “significantly disrupt the outdoor industry,” and wants to get shoppers as excited about the product as it is.

It’s a big unanswered question whether it can do that when there are other very effective technologies on the market. When Gore-Tex appeared, it didn’t have the same competition. But people are always going to look for the best way to stay dry and warm (but not too warm). If The North Face can convince shoppers Futurelight is the best option, it could pay out for years to come.

This story has been updated with information about Futurelight’s three-layer construction.