Varda can't yet land its space drugs in the US—but what about Australia?

The in-space manufacturing business has a delivery problem.

The hardest part of making something in space might just be getting back to Earth again.

Suggested Reading

Varda Space Industries, an LA startup, launched its first prototype factory into orbit in June. The spacecraft contained an automated fabrication system to create an HIV/AIDS drug called ritonavir, the company hopes that forming the crystal molecules that make up the drug in microgravity will result in purer samples than when it is manufactured on Earth.

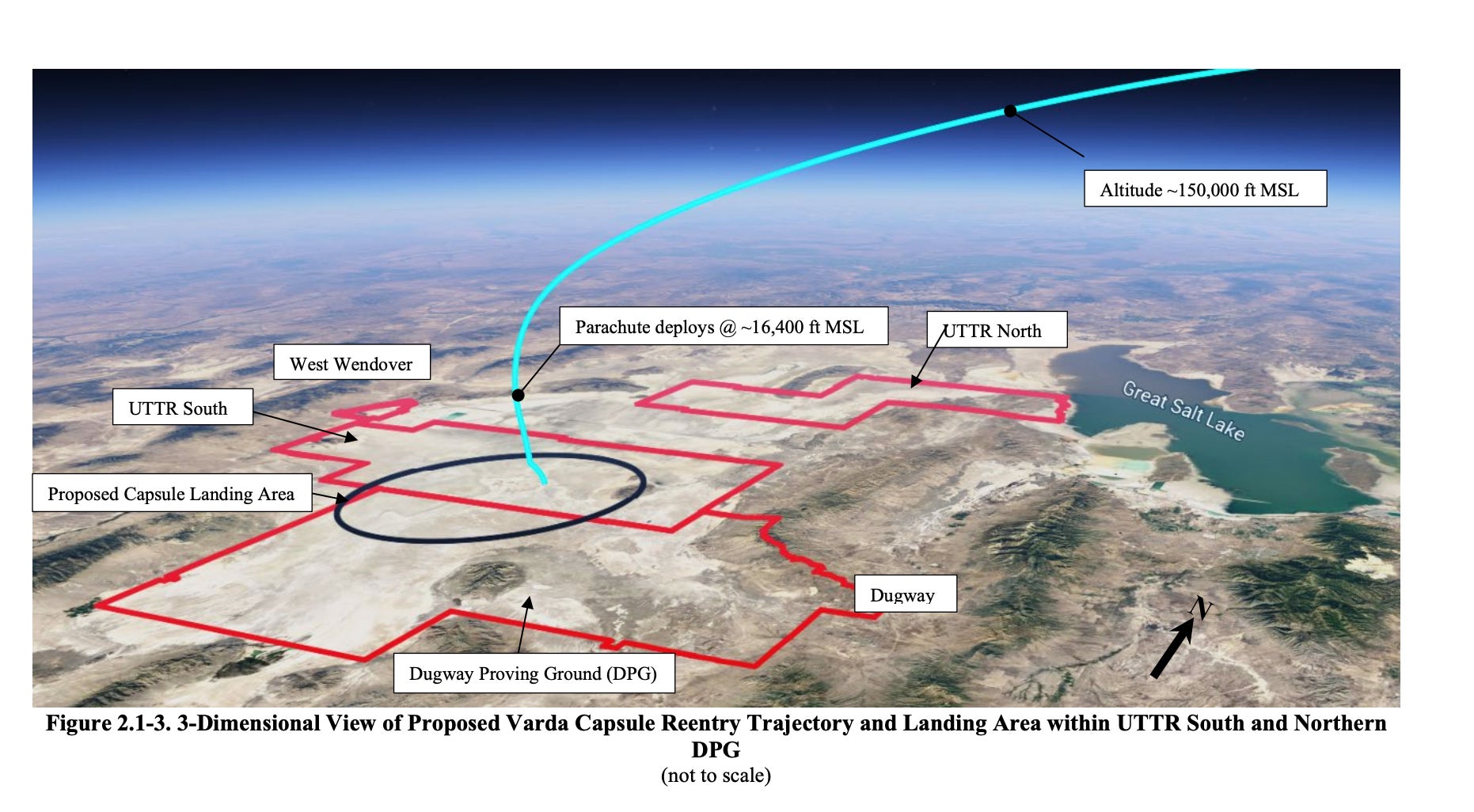

To prove it, they need to get the samples back to Earth and test them, sending a 90 kg (198 lb) capsule that’s one meter in diameter back through the atmosphere, where it will deploy a parachute to float gently to the ground.

Thus far, however, Varda hasn’t been able to win the Federal Aviation Administration’s permission to bring its samples home; the agency okayed the launch of the company’s orbital factory but has thus far denied requests to bring the recovery capsule back down. Delian Asparouhov, a co-founder and president of Varda, says the company still plans to return its first samples to the US Air Force’s Utah Test and Training Range (UTTR), the same place to which a NASA mission just returned samples from a distant asteroid.

To create more certainty for the company’s next mission, expected to launch next year, Varda announced a new partnership with the Koonibba Test Range in Australia. That 23,000 sq mi chunk of land is owned by the Koonibba Community Aboriginal Corporation and operated by the company Southern Launch, which operates rocket launch facilities in Australia. There is less activity both on the Koonibba range and above it than at UTTR, which could make coordinating a landing easier. But because it is a US company, Varda will still need permission from the FAA to re-enter the atmosphere, as well as that from Australia’s aerospace regulators.

Varda had hoped to return its first samples in September, but the FAA and the US Air Force denied its request for permission, saying that the company had not met regulatory requirements. The company is still seeking permission to bring the samples back, but it is not clear when that will be possible. The company chose ritonavir as its first substance to experiment with in part because it has a long shelf life when facing delays like this one.

Asparouhov pointed to three challenges to getting government approval for re-entry. The first is the schedule at the range, where Varda’s needs take a backseat to national security. Then, when those dates are available, the company needs to begin licensing talks with both the FAA Office of Commercial Space and with FAA Air Traffic Control, since airspace needs to be cleared before the capsule can return. Finally, the company needs to provide a rigorous technical analysis demonstrating that its capsule will land where it’s supposed to, with sufficient margin to guarantee public safety, the FAA’s top priority. All that needs to be ironed out ahead of time, since at the point at which Varda’s reentry capsule fires its thrusters to return to Earth, there’s no going back.

The world of reentry licensing is new; the FAA adopted the rules to allow it in 2020, and thus far the only licensed vehicles have been SpaceX’s Dragon spacecraft and Boeing’s Starliner, both designed to carry astronauts with NASA’s oversight. Varda’s spacecraft is intentionally simpler and cheaper, which may make the FAA scrutinize it more closely. Some reports have suggested that the government wants more granular safety analysis from Varda, but Asparouhov says he’s confident in his engineers’ work.

At the same time, part of the issue is staffing at the FAA, which is charged with supervising ever more space activity but hasn’t seen commensurate increases in its personnel. Representatives from SpaceX, Blue Origin, and Virgin Orbit told senators that more resources were needed at a hearing this week, comments echoed by former FAA space chief Wayne Montieth. The FAA’s engineers need to carefully check out the engineering work done by private companies, and the requests for launches and reentries are piling up.

Regulatory challenges are part of the challenge of developing new business models in space. Peter Beck, the CEO of Rocket Lab, which built the spacecraft that carries Varda’s orbital factory, frequently says government relations are a third of the job when carving out a new space businesses. Varda is one of the first private companies seeking to license an autonomous return capsule, but it won’t be the last, so Asparouhov sees the current challenge as pathbreaking for the entire industry, not just his own firm.

Australian prime minister Anthony Albanese is set to visit the US next week, and Varda’s Asparouhov says he plans to be in Washington to meet the visiting delegation and talk to US officials about smoothing the path for orbital goods to come back home again.