How to prep for the apocalypse, corporate-style

If stability is your thing, then really, this isn’t the greatest time to be alive.

If stability is your thing, then really, this isn’t the greatest time to be alive.

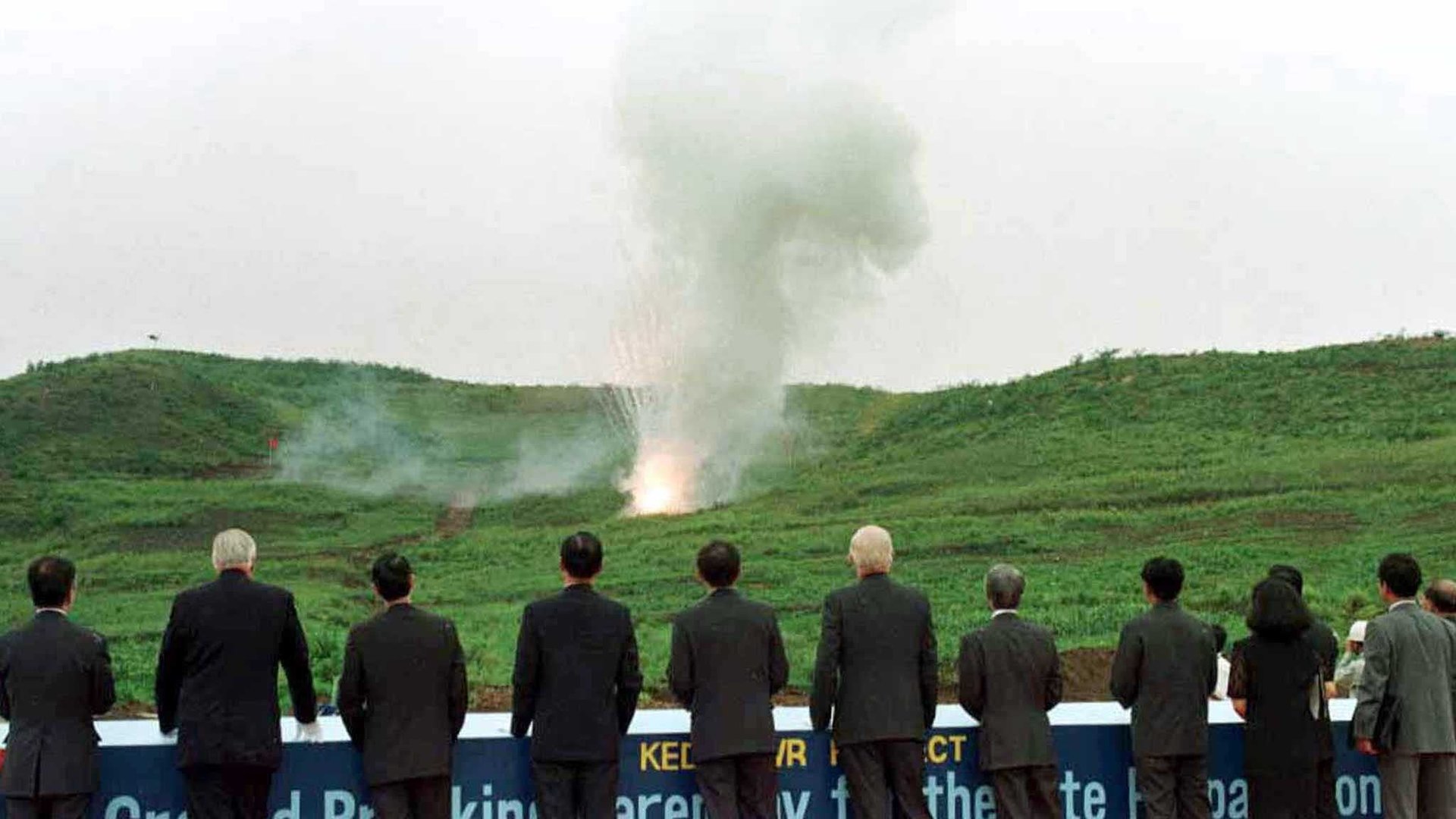

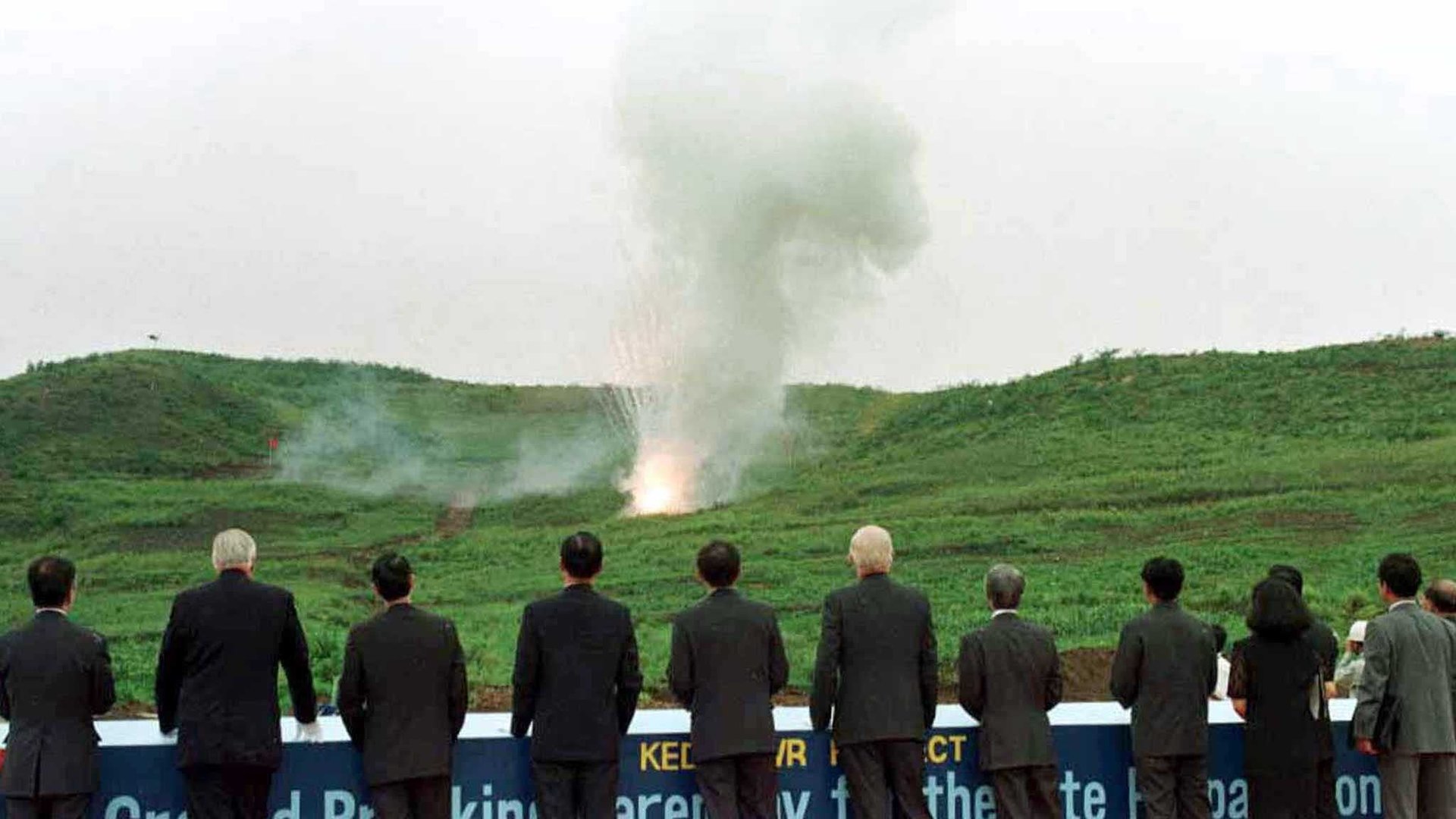

The World Economic Forum recently identified no fewer than 30 major threats to global security. Their matrix of anxiety includes nuclear war, an event that—thanks to the volatility of both Donald Trump and Kim Jong-Un—the organization deems arguably “closer than it has been for decades.” Next month’s Olympic Games in South Korea take place just 50 miles from the border of a country that has threatened it with annihilation.

Wealthy individuals may be stocking up on survival bunkers, potassium iodide, and private planes (paywall), but what does fear look like at the organizational level? How do corporations prepare for the worst?

Risk management consultants like Kroll, Pinkerton, and Control Risks specialize in helping companies prepare for potential disasters. Yet despite the ominous noises from Washington and Pyongyang, representatives from the firms said there hasn’t been any increase in client queries about safeguarding against a nuclear attack in recent months. The vicious hurricane season of 2017 sparked more calls than Trump’s tweets. And in any case, the kind of disaster planning that large-scale firms invest in focuses less on the particulars of the disaster itself than on what comes next.

“Your plans don’t identify a specific cause. On Sept 10th 2011, there were no companies that had a specific plan that addressed airplanes flying into buildings,” said Christopher Berry, senior director in the security risks management practice at Kroll.

The key to developing a crisis plan that works in every situation is deceptively simple: Identify the team that will kick into gear when disaster strikes, and make sure everyone on it knows what to do.

This is harder than it sounds. Part of the reason that companies bring in external consultants like Kroll and its counterparts is to have fresh eyes that can point out the environmental and organizational dangers that humans all too easily overlook.

“We as people tend to adapt very well to our environments,” said Jason Porter, a vice president at Pinkerton. “If you’re constantly exposed to risk, it becomes normalized, [and] amplifies the vulnerabilities.”

This habituation leads to companies at times failing to adequately plan precisely for the threats they’re most likely to face. An organization that does business near the US-Mexico border may become desensitized to narcoterrorism, Porter said. Or a business that has survived hurricanes in the past may become complacent about its storm contingency planning, reasoning that things have always worked out fine before.

Organizations, like humans, are subject to the availability heuristic. This quirk of human cognition makes us believe that because a particular event is easier to imagine than others, it must also be more likely to occur. In the months after the Sept. 11 attacks, road accidents rose in the US as travelers frightened of airplanes took the far more dangerous decision to travel by car. People in the US fear terrorism more than guns, despite the fact that they are far more likely to be killed by the latter than the former.

From a corporate perspective, the prospect of a catastrophe that kills or harms employees is horrifying. Businesses understandably spend enormous amounts of money and effort to prevent such emergencies. But problems arise when they fail to give proportional attention to less dramatic but more likely threats.

Companies will obsess over something “like the security of individual employees traveling to south Philippines, instead of the fact that the passwords [to sensitive systems] are ‘password’ or ‘administrator,’ or are written on pieces of paper,” said Cory Davie, partner and head of the Australia Pacific practice for Control Risks. (It’s not as farfetched as it sounds. Days after Davie’s comments to Quartz At Work, an Associated Press photograph showed the password to an unspecified system in Hawaii’s emergency management agency stuck in plain sight on a Post-It note.)

The problems identified in the World Economic Forum’s matrix—unmitigated climate change, rising inequality, cyberattacks—are complex and multifaceted. Coping with their aftermath will be too, which gives reason to suspect anything marketing itself as an easy fix.

Take, for example, Plan B Marine. In the event of a disaster that renders Manhattan uninhabitable—or at the very least, super inconvenient— catastrophe-conscious Manhattanites who have leased one of the company’s $4,500 per month boats will make their way to a West Side dock and pilot themselves to the comparative safety of New Jersey. Packages include boat-driving lessons.

“You can’t count on a captain or somebody else driving you, because they wouldn’t be able to get to you in an event,” explained Chris Dowhie, who co-owns Plan B with his wife Patricia.

For the record, Dowhie imagines the boats’ ideal situation as a blackout or other problem that makes it extremely difficult to conduct business in New York, not a nuclear attack. He estimates that half their clients have contracted their services for corporate reasons and the other half for family use.

“Every Good Chief Executive Needs a Plan B,” the company’s website says. “Your job is to see to every contingency. Disaster recovery… business continuity… it’s up to you to leave nothing to chance. You need to be prepared so that your company can continue to operate no matter what the situation.”

But escaping the island isn’t as complete a solution as it may sound at first. If Manhattan has shut down, how will you get to the dock? How are you going to alert your employees that it’s boat time if all the communication systems are down? Where exactly do you think this boat is going to go, and what awaits you when you get there?

“The danger is getting one piece of the pie and then thinking, right, that’s sorted,” Davie, from Control Risks, said. “There are so many pieces of that puzzle. That’s the danger I see with people thinking they have ‘solutions’ for those catastrophic problems.”