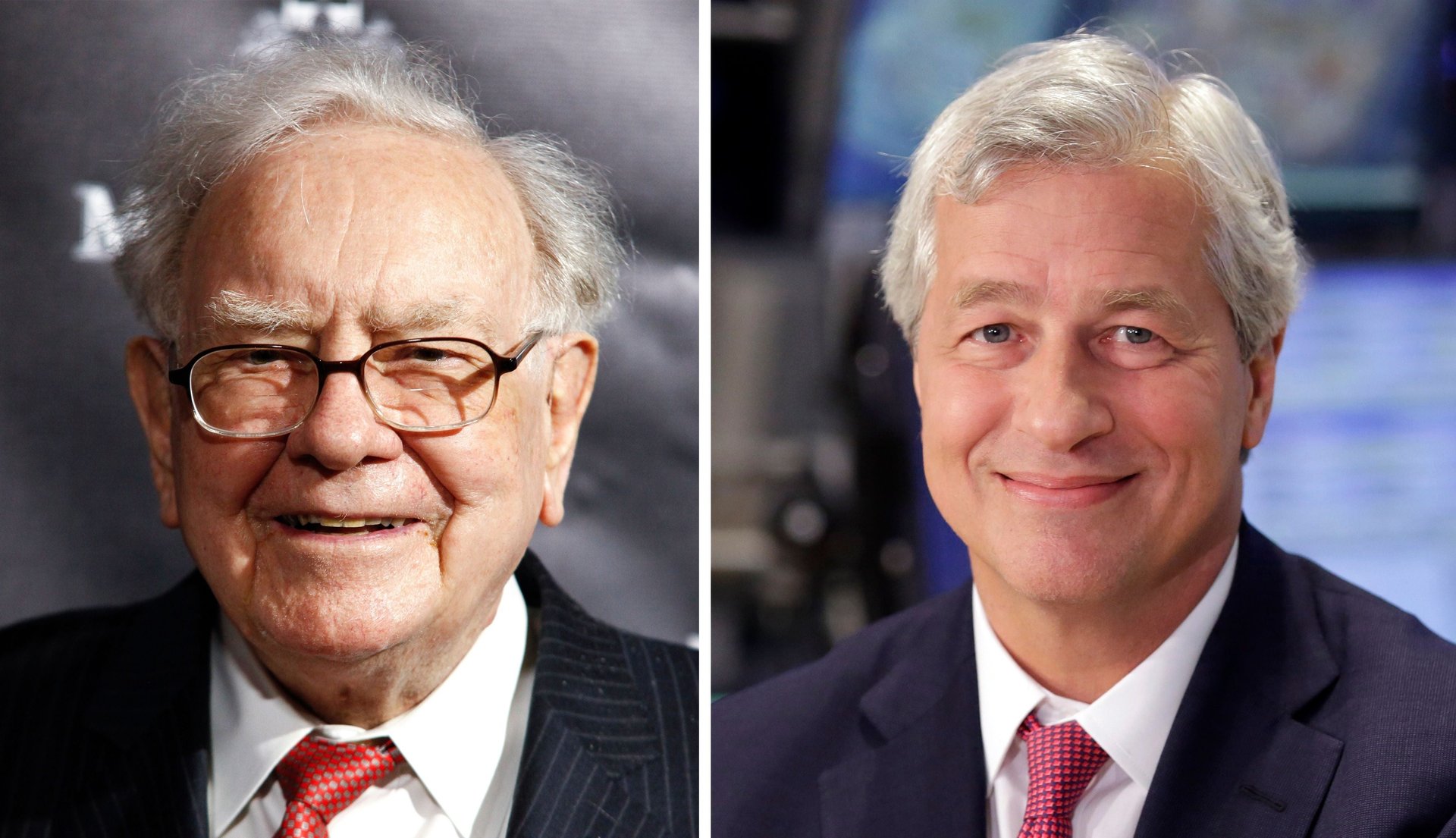

Warren Buffett and Jamie Dimon are telling companies to quit giving quarterly earnings guidance

To break corporate America and its enablers on Wall Street of a dependence on short-term thinking, some of the US’s most prominent business leaders, led by Warren Buffett and Jamie Dimon, are calling for companies to stop giving quarterly earnings guidance.

To break corporate America and its enablers on Wall Street of a dependence on short-term thinking, some of the US’s most prominent business leaders, led by Warren Buffett and Jamie Dimon, are calling for companies to stop giving quarterly earnings guidance.

Those numbers are used by Wall Street analysts to build their earnings estimates, the primary scorecard used to measure a company each quarter. For investors, there are few words more discouraging than “missed earnings estimates.” When a company falls short of expectations in its quarterly earnings report, share prices are sure to fall, no matter what else the company has accomplished.

The emphasis on quarterly earnings, and the importance of beating estimates, is warping American business and the economy, argue almost 200 CEOs who belong to the Business Roundtable, a lobbying organization. Short-term thinking leads corporations to choke back on hiring, and to starve research and development of the spending the fuels long-term growth. The pressure of quarterly earnings is one reason fewer companies are interested in going public, preferring the slower growth that comes with being private than the scrutiny that comes with being listed.

“I’ve seen how pressure to produce forecasted results distort business decisions in a myriad of ways,” said Buffett, the legendary investor and chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, in the Roundtable’s statement. Buffett and Dimon, the CEO of JPMorgan Chase, also signed their names to an editorial that ran in today’s Wall Street Journal that reinforced the message.

While CEOs may feel the pressure of short-term thinking is on the rise, the trend of providing earnings forecasts is actually on the decline. The number of S&P 500 companies offering quarterly guidance fell from 36% in 2010 to 28% last year, according to Focusing Capital on the Long Term (pdf), a group devoted to battling short-termism in business. According to the group, few investors actually want it: In a 2006 survey of 2,686 financial analysts, 76% agreed that companies should drop quarterly forecasting.

Not all observers agree that short-term thinking is damaging, or that it even exists. Steven Kaplan, a University of Chicago finance professor, has written about how the pearl-clutching over short-termism has been around for decades, with no evidence of a problem (pdf). Stock indexes continue to climb, corporate profits are up, and increases in productivity are evidence that investments in innovation and technology are paying off, he argues.

There’s also the argument that the financial system should be biased toward providing investors with as much information as possible. After all, they are the company’s owners, as the Wall Street Journal’s Charley Grant notes:

Since it’s unlikely the government will step in to ban guidance, ultimately it will be up to individual companies. As with much of corporate behavior, the market will decide.