Raising venture capital is often the difference between a shot at success and never getting a chance.

Despite the celebrated stories of companies like MailChimp that were able to grow without accepting outside investment, funding is what gives most startups the ability to compete with more established companies for talent. It lets startups focus on building a useful product without having to worry about revenue. It lets startups invest in marketing to get their products into the hands of users. When all of your competitors are raising money, the amount you raise matters. And women still aren’t getting enough of it.

In Quartz’s analysis of top founders, we found that since 2013, the average male entrepreneur has raised more than four times more money than the average female entrepreneur. Startups without a male co-founder raised a measly 2.2% of all venture capital raised in 2017, according to data from Pitchbook. Another study from the Boston Consulting Group found that of 350 startups in the Boston area, women raised less than half as much money as their male counterparts, yet earned 78 cents per dollar invested compared to 31 cents for the men.

So, if women founders are earning a higher return on investment than men, why is there still such a large gender gap in fundraising?

The funding gender gap is still real

In some ways, the venture capital industry is changing. A number of women in the startup world have come forward to share their stories of harassment and discrimination as part of the #MeToo movement. As a result, prominent VCs like Binary Capital co-founder Justin Caldbeck and 500 Startups founder Dave McClure have lost their jobs. Women-founded companies raised $12.3 billion in 2017—an all-time high, according to Pitchbook.

But in relative terms, 85% of venture capital funding in 2017 still went to male-led organizations. This is on top of the fact that the percentage of startups founded by women in a year, 17%, has not changed since 2012. While we need to encourage more women to start companies, the only way to close the gender fundraising gap is to invest in them.

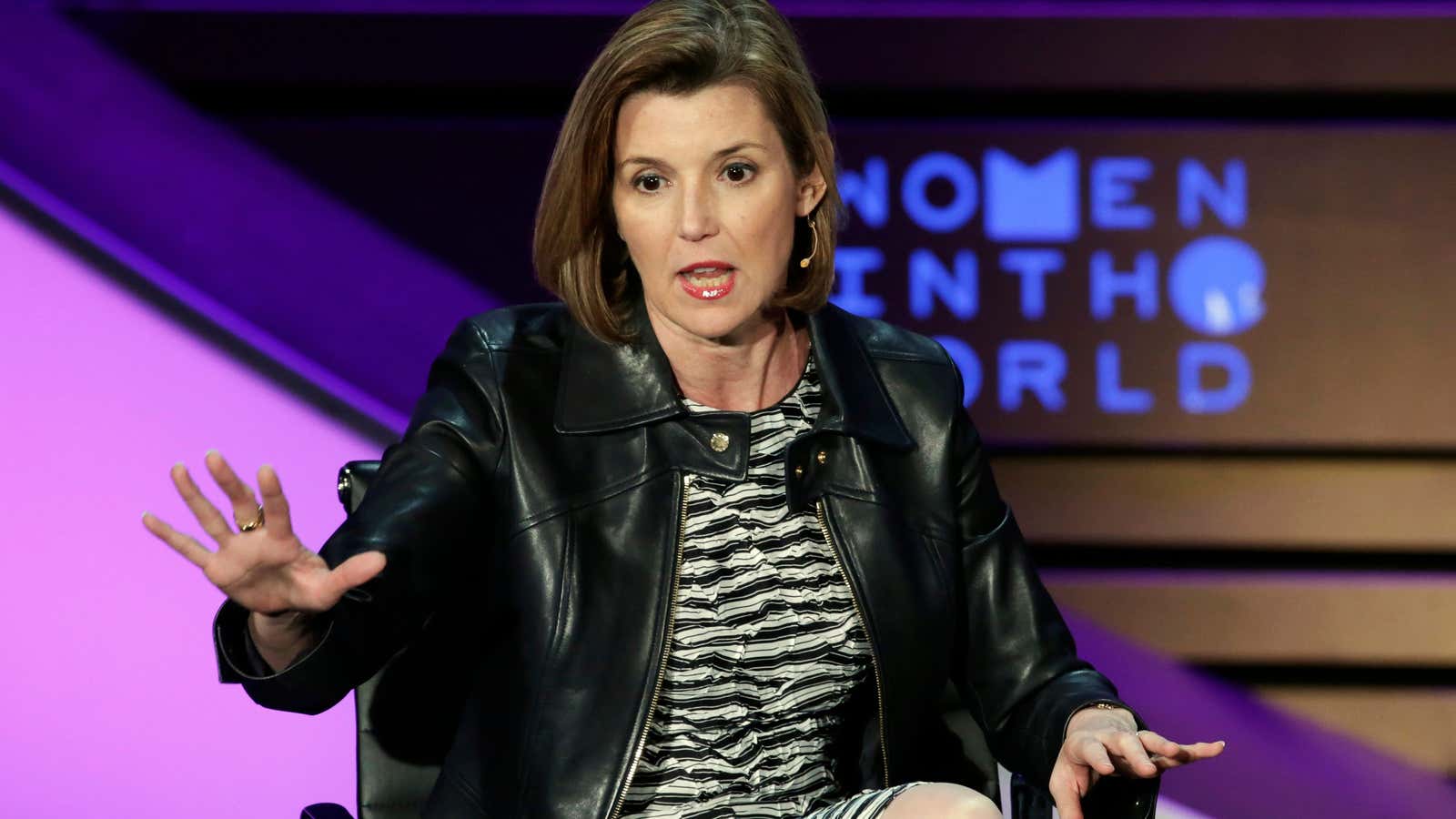

Sallie Krawcheck, the founder of the women-focused investing platform Ellevest, believes the shift has to start with a change in perception.

“People assume women are more risk-averse, but I think of them as more risk aware,” Krawcheck told Quartz. “Where some [investors] might see women not maximizing their potential returns, I see them managing their potential risk.”

Krawcheck, as the former CEO of Merrill Lynch and Citi Wealth Management, has spent over three decades managing risk. Though academic studies have proven that there is truth to the idea that women are, on the whole, more risk averse than men, that shouldn’t impede their ability to grow a business in the face of uncertainty.

Take the online retail service Stitch Fix, which was founded by Katrina Lake and Erin Flynn in 2011. The company raised less than $50 million before its IPO in 2017—a fraction of the capital raised by other companies like Snap ($4.9 billion), which also went public that year. Yet Stitch Fix had a couple of years of profitability before going public, a rare feat for a venture-backed startup. Since its IPO, Stitch Fix’s stock price has more than doubled. (Snap has not fared as well.)

For some founders, like Jessica Mah, co-founder of accounting software platform InDinero, raising large amounts of capital is a risk in and of itself. “Lots of female founders don’t want to [raise more money like the guys],” Mah told Quartz. “I could, but I think it’s a dumb idea.”

Mah, who has raised less than $10 million since her company started in 2009, isn’t alone in thinking venture capital can put undue pressure on startups to grow, which can ultimately lead to a company’s downfall. But just because a woman-founded startup doesn’t need to raise more money doesn’t mean it shouldn’t have equal access to VC.

Change starts who’s doing the investing.

Over 90% of all venture capitalists are men

Many believe the first step to investing in more women is to have more women doing the investing.

“[Venture capitalists] are claiming that they’re supporting women founders, but numbers talk,” says Lu Li, the founder of Blooming Founders, a London-based community built to support women entrepreneurs. “You can’t truly invest in the future if you don’t understand how half of the population lives.”

In the last several months, many prominent venture capital firms—First Round Capital, Union Square Ventures, Redpoint Ventures, among others—have added their first female partner. Though a significant—albeit small—improvement, the lack of women in VC is still striking. Data from Crunchbase show that only 8% of partners at the top 100 VC firms are women.

Still, having more women VCs is far from a silver bullet. Stephanie Palmeri, a partner at Uncork Capital, summed up the problem with treating women VCs as a cure-all for the gender fundraising gap at 500 Startups’ PreMoney conference last year: “At the end of the day, female founders shouldn’t be constrained to work with only female VCs. If we invested only in people who look like us, we would be in trouble as an industry. That’s really one of the reasons why we are in trouble as an industry.”

In the mind of Caitlin Strandberg, a principal investor with Lerer Hippeau, the best way VCs can aid in helping women founders succeed (besides investing) is to create a support system for underrepresented entrepreneurs.

“You can’t have one female founder dinner and call it a day,” Strandberg told Quartz. “This is an industry where we play the long game, so when it comes to diversity and inclusion we have to have a long-term mentality as well.”

In April, women leaders in the tech industry came together to launch All Raise, a nonprofit that hopes to accelerate the success of women founders and funders. Their first initiative, Female Founder Office Hours, created a mentorship program to connect women entrepreneurs and VCs. We’ve also seen the growth of new venture capital firms, like Female Founders Fund and Built By Girls (BBG) Ventures, in the past few years that exclusively invest in women-led companies.

Then, there are venture capitalists like Backstage Capital’s Arlan Hamilton, who raised a $36 million fund earlier this year to invest in black female founders. “My big idea is that investing money, time, resources, access, belief—all of that—into black people, Latinx people, all people of color, and women in the US is not something that should be looked at as doing us a favor,” she told Quartz. “It is doing you a favor if you are a white male because we are the future.”

Whereas some VCs see investing in underrepresented groups as a pipeline problem, Hamilton sees investing in women and people of color as the biggest opportunity for investment. But creating a more equitable ecosystem is not incumbent on investors alone. Women founders can use their experiences to teach the next generation.

Women founders need to know they’re not alone

“There is a general perception among female entrepreneurs that they are going through these struggles in a vacuum,” Anna Whiteman, a VP at Coefficient Capital, told Quartz. “But sharing common experience will help to build solidarity and will start to shift the balance of power away from the venture capitalists and back to the entrepreneurs, where it should really lie.”

But not all women founders also want to be leaders in the gender equity movement. For some, running a company while also being tasked with supporting the female-founder ecosystem is the double duty we’re all-too-familiar of expecting of women.

Melissa Pancoast, the founder of the financial platform The Beans, has been a vocal advocate for gender equity, but she also understands why some women might want to keep their heads down and build their businesses without being a spokesperson for the movement. “No one is going to fund you to be a social-change agent,” she told Quartz last year. “They’ll fund you because you have the potential to make a change-making company.”

But visible women leaders are important. Steph Korey, the co-founder of the travel company Away, has struggled with wanting to drop the “female” tag that always gets placed next to her founder title, but she’s come around to embracing the significance of being a woman and a leader. “Because women have such few role models,” Korey told Quartz, “the few women founders that do exist need to be more visible.”