The most tedious part of my job changed my relationship with gratitude

Some people keep gratitude journals. I type generic terms into search bars of news photo archives.

Some people keep gratitude journals. I type generic terms into search bars of news photo archives.

Though the approach is different—the first a daily inventory of the good things you have in your life; the latter a daily meditation on the bad things you do not—the result, I’ve found, is much the same.

Looking through news photo libraries didn’t start as some sort of creative self-improvement project. It’s part of my job. Like many media organizations, Quartz subscribes to Reuters Pictures and AP Images, which gives us access to photos from thousands of photojournalists all over the world. When I was a Quartz technology reporter, using these subscriptions was fairly straightforward: I’d search for a term like “Facebook,” quickly locate a photo of Mark Zuckerberg’s latest public appearance, and add it to my story. The entire process took about three minutes.

But when I became an editor for Quartz at Work, the quick task of finding a photo to run with an article turned into a prolonged scavenger hunt. Quartz at Work covers concepts like leadership, careers, and creativity. The photojournalists shooting for Reuters and AP are typically focused on people and news events. Typing “leadership” into the search bar of AP’s photo site returns images of various world leaders at podiums; typing “career” mainly generates photos of football players, and typing “creativity”… also generates a surprising number of football photos.

And so, I came to rely on metaphors. In searching for an image to pair with an article about “radical transparency,” I typed “bubbles,” hoping for an example that was particularly (radically, even) clear. An article about “dual-career marriage” provoked the search phrase “doubles figure skating Olympics.”

Sports metaphors have become particularly reliable (my apologies to the athletes whose epic falls have become my go-to images for “failure”), as have object metaphors (ladders, staircases, relay batons, score cards, and finish lines) and angry traders (clearly “stressed at work”).

Finding a pitch-perfect photo, or even just an appropriate one, sometimes takes the better part of an hour. No pictures of “job you love”? How about searching for “happy” or “Valentine’s day heart”? Maybe “office cubicles”? “High five”? “Smiley face?” Sometimes it feels like a tedious word-association game.

Even when I land on a metaphor that makes some sense, typing generic words into the search bar of photo search sites rarely leads to the nice office-setting photo that I really would like. Often it leads to something completely unexpected (like a whole series on “checker man,” who despite his game-inspired name is absolutely not appropriate for illustrating an article about “strategy”).

I’ve found a few consistencies along the way. For example, there are two categories of photos that, whether you’re searching for “laptop in coffee shop” or “vacation,” will almost definitely appear:

- Photos featuring the British royal family (seriously, whether you’re looking to illustrate teamwork, schools, reading, math, or mental health, the royal family has staged a related photo op)

- Photos that document unspeakable tragedy

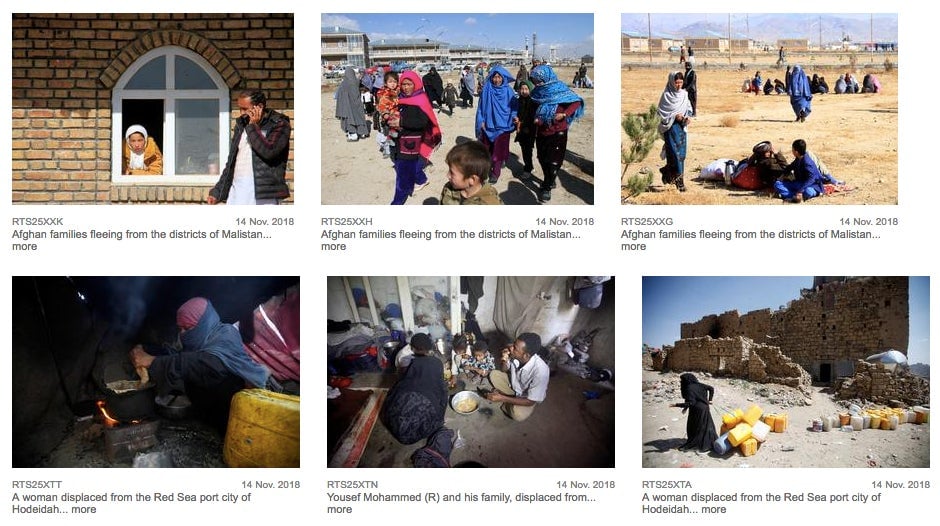

The latter surprised me in the beginning. I would search a term like “family” expecting happy photos of togetherness, perhaps (fingers crossed!) featuring a harried working parent. What the newswires gave me instead were photos of families in an array of refugee camps: Malaysian families who’d escaped to Bangladesh; Afghan families who were refugees in Greece; families waiting in Tijuana, Mexico to apply for political asylum in the US. And, of course, the British royal family.

Searching for “friends”—they’re important to have at work—led to a memorial for a murdered 14-year-old girl whose body was found in a recycling bin; a funeral for someone who died of AIDS in a country where it’s nearly impossible to find care for the disease; and four Palestinian young people who’d been involved in, the caption said, “conflicts,” each on crutches and missing a leg.

Eventually I came to expect that I would come across tragedy in my daily photo searches. But I don’t think the breadth of its particulars will ever cease to be surprising.

A search for “cubicles” returns images of office workers, but also of an elderly man living in a cage in Tai Kok Tsui; “water cooler” produces not chatty co-workers, but a school in Detroit where fountains are not safe to drink from; “bias” does not surface photos of job interviews but of a concentration camp that is being turned into a museum. “Work from home” is apparently interpreted by the databases as work ON homes—after floods, earthquakes, and fires.

It’s not the existence of these sad stories that makes me feel like I’ve been knocked off of my feet—I’ve always read the newspaper. It’s that I’m surprised when I find them filed under common words, right there next to the perfectly coiffed royal family.

Finding tragedy where I expect to find offices, meetings, and working parents reminds me of how easy it is to take my comfortable life for granted. In my tiny corner of the world, the word “family” is not most often employed to describe one that has been dislocated, and the word “friendship” doesn’t first connote a funeral. A “cubicle” is a place where people work, not where they sleep. And “burning man” is a festival where people go to have a good time, not a man engaged in an act of desperation and protest. All of these are blessings.

They’re not the kind of blessings that I’d ever think to write down in a gratitude journal, and they can’t be captioned with #blessed in an Instagram photo. In the context of my own life, they’re normal, which makes them invisible. It takes some outside perspective—from a friend, conversation, book, experience, or, you know, a photo archive search—to see them.