The last time Atul Gawande started a company, he named it after a Greek myth.

Ariadne Labs, based in Boston, Massachusetts—where Gawande also works as a surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and teaches at Harvard—has been trying since 2012 to innovate in an area that has historically resisted innovation: healthcare delivery. You may not have heard of Ariadne, but you’ve certainly heard her story. It’s the one about the Labyrinth and the Minotaur.

If you don’t know her name, it’s because most tellings cast Theseus, the prince of Athens who eventually slays the monster, as the hero of the tale. But a closer read makes clear that, really, it’s Ariadne, the princess of Crete and the minotaur’s half-sister, who matters. She falls in love with Theseus, and saves his life by wisely instructing him to take a ball of twine and attach the thread to the labyrinth’s entrance so he can find his way through the maze, and by bravely risking her life to hide his sword so he can retrieve it in time. Theseus kills the minotaur, escapes the labyrinth, and leaves Crete with Ariadne, bound for Athens and marriage.

Explaining his new company’s name and mission in 2013, Gawande told WBUR public radio, “We’re in the simple threads business, to show there are ways out of the labyrinth of healthcare complexity.”

Perhaps the most influential thing the lab has worked on is the development of healthcare checklists, based on Gawande’s hugely influential “safe surgery checklist.” After Gawande’s original checklist was implemented in eight hospitals as part of a study in the mid-2000s, post-surgery death rates in those facilities fell by 50%. Today, the surgery checklist is used all over the world, and Ariadne Labs has attempted to replicate its success by bringing checklists to other areas of healthcare delivery. It’s not a sword cutting off the head of the monster; it’s the twine helping to guide better decision-making.

Another thing that was likely left out the version of the Labyrinth myth you read in grade school: Ariadne and Theseus do not live happily ever after. On their way back to Athens, Theseus abandons Ariadne on the island of Naxos, where she dies, alone, as he sails back home.

Ariadne Labs is far from dead, though Gawande has stepped down from his role of executive director (he’ll remain chairperson of the company), and there are genuine questions about whether simple threads will always work. Many of Ariadne Labs’ recent efforts, including the highly publicized deployment of a World Health Organization-sponsored checklist to reduce deaths among newborns and their mothers in India, have failed.

Gawande, who has been writing and speaking on the problems of the US healthcare system for most of his adult life, has long bemoaned the field’s resistance to innovation. As an influential book author, New Yorker contributor, and public speaker, Gawande has become one of the foremost champions of change in healthcare delivery and policy. His ideas are about to be put to their biggest test yet. In January, three of the biggest and most powerful American companies—the tech juggernaut Amazon, banking giant JPMorgan Chase; and Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway holding company—announced they were forming a joint healthcare venture; in June, they chose Gawande to run it.

Nearly six months later, almost nothing is known about Gawande’s plan for his second startup, other than that it will seek to provide the combined 1.2 million employees of its three sponsor companies with better healthcare at a lower cost to the employers than exists now. No one involved in the venture is speaking to the press about it. Emails sent to Gawande directly were rerouted to public relations, and attempts to speak to him by phone and in person were similarly forestalled.

But based on Gawande’s prior work, and on recent trends in employer-sponsored healthcare, it’s not hard to imagine what’s in store for the Amazon/JPM/Berkshire partnership. Despite huge improvements brought on by the 2010 Affordable Care Act, the US still lags far behind other similarly wealthy countries when it comes to healthcare penetration and efficacy. Gawande, who cut his teeth as a member of the Clinton administration’s healthcare reform team, has long been a critic of how care is delivered in the US.

Companies across all sectors, ranging from tech and financial services to retail and manufacturing, have, in the past five years or so, started to tweak their employee health programs to stem the rising costs of healthcare, which impact the bank accounts of both employers and employees. But simultaneously, facing a competitive labor market, more employers are seeing better employee healthcare as a differentiator that can help them recruit and retain the best of the best.

The problem is, the last time employers used healthcare this way, they laid the tracks that led to the very problems with the US system they’re now trying to solve.

Why do Americans get healthcare from their employers?

The fact that most Americans get their insurance from their bosses has become such a given it seems strange to even question it. But really what’s strange is the system itself.

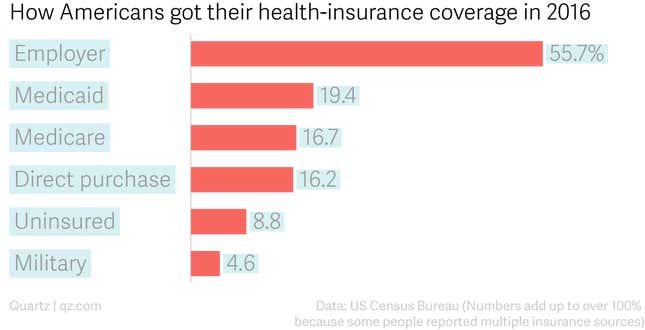

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, in 2016, about 56% of Americans got health insurance through their employer. No other source of coverage is anywhere close.

That’s unique among wealthy, industrialized countries. “It doesn’t have to be this way. Other countries look at this model and go ‘that’s insane,'” says Bob Galvin, who runs Equity Healthcare, a Blackstone subsidiary that works to improve employer-sponsored healthcare across the private-equity firm’s portfolio of companies.

The strangeness is the result of a confluence of a unique set of circumstances in World War II- and post-war-era America. During the war, a diminished pool of potential workers forced employers, many of which were still ramping up work after the Great Depression, to compete more aggressively for the limited supply of labor. In 1942, US president Franklin D. Roosevelt’s National War Labor Board passed a rule preventing employers from raising employee wages—and exempted health insurance from the cap. A year later, the Internal Revenue Service decided that employers’ contributions to group health insurance policies were exempt from taxation.

Employers, of course, saw the opportunity: save money on their side, and dangle health insurance coverage as a carrot to bring in new hires and keep current employees who otherwise weren’t going to see much in the way of financial incentives from competitors.

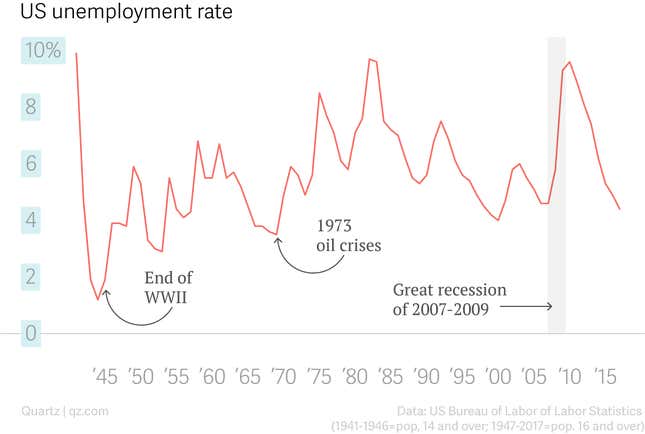

In the post-war years, the US economy was buzzing. In 1944, unemployment dropped to 1.2% (pdf). For context, from 1969 to 2017, the unemployment rate never fell below 4%.

Low unemployment, combined with incentives to buy insurance through employers, meant very few Americans sought healthcare coverage outside of work. It all seemed so clever that “advocates for universal coverage shifted their strategy,” says Judith Feder a professor at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy. Instead they focused their attention on getting the government to help a key demographic that couldn’t work: the elderly. This was another success, but in the process, it “legitimized employer sponsored insurance,” says Feder, creating a system wherein the US government essentially subsidizes private insurance systems for employees and their families, and offers public health insurance to only those specifically not expected to work. “The people who were left out, who worked low-wage jobs and didn’t get insurance through their employer, didn’t get Medicaid unless they were parents of dependent children,” Feder says. “Then, any attempts at trying to expand [the government programs] was seen as threatening the coverage people already had.”

The failure of US healthcare, by the numbers

Within a matter of decades, the system was broken, with millions of Americans left without insurance and the insured and uninsured alike facing spiraling healthcare costs.

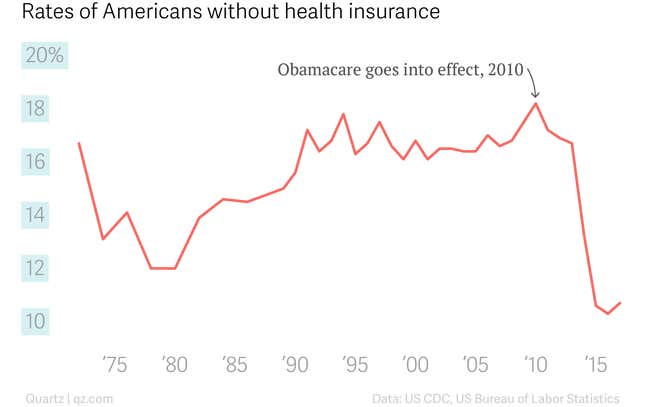

According to the US Census Bureau, 8.8% of the US population, or 28.5 million people, did not have health insurance at any time in 2017. That’s a huge improvement over the 16% average in the 1990s and 2000s—the Affordable Care Act of 2010, also known as Obamacare, solved one of the huge problems created by the US’s employer-dominated insurance market. But the ranks of America’s uninsured are still roughly equivalent to the entire population of Australia.

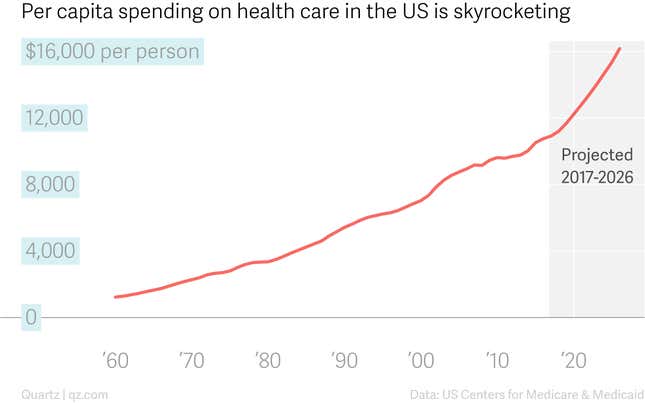

Troublingly, even post-ACA, the country keeps spending more on health every year with little to show for it. In 2016 (the most recent year for which data are available), the US spent $3.3 trillion, or $10,348 per person, on health, a 4.4% increase from 2015. The US Department of Health projects those numbers to keep going up at faster and faster rates.

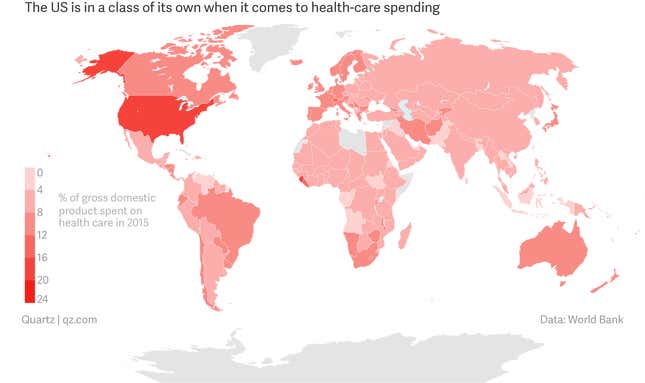

Another way to look at it: in 2016, health spending took up 17.9% of the US’s entire GDP. That puts the US quite literally in its own class compared to every other country, rich or poor, democratic or despotic, in the world.

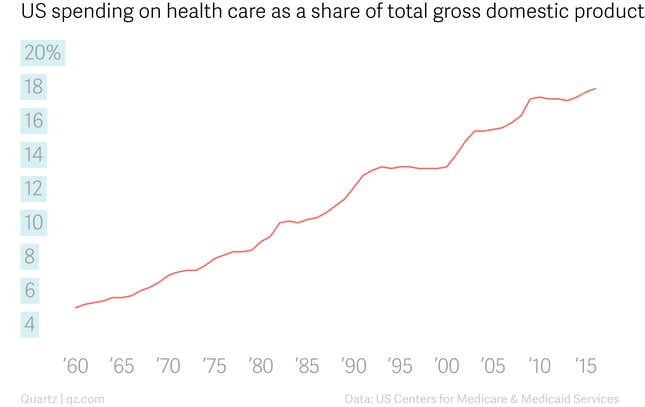

And that number, too, has been on the rise for decades.

That all might be fine—if Americans’ health was improving. But by most key measures, it’s not.

The US has a higher infant mortality rate than other wealthy, industrialized countries. Same goes for maternal mortality: American mothers are far more likely to die during and after childbirth than mothers in countries the US sees as its peers. Relative to comparable countries, the US has a higher mortality rate for heart diseases, lung diseases, nervous system diseases, endocrine and metabolic diseases, and mental health diseases. Americans also are more likely to die from accidents, suicides, and other external causes than people in similarly situated countries. In all of these key metrics, the US is getting worse, despite the growing amounts of money thrown at the problem.

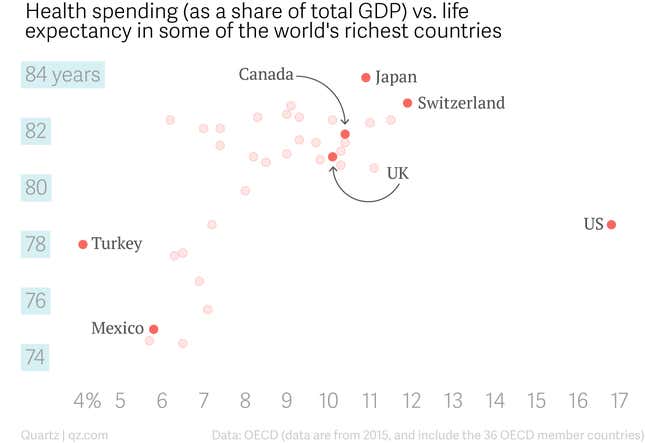

The country, essentially, gets less for its health dollars than any other in the world. The simplest way to measure the overall health of a country’s citizens is through life expectancy. The US, with an overall life expectancy of 78.6 years at birth, rates relatively well compared with the global average of 72. But life expectancy in the US is basically the same as that in countries like Turkey and the Czech Republic, which spend far less of their overall GDP on health. Meanwhile, in countries like Canada and Japan, life expectancy is significantly higher than in the US, despite much lower health spending.

Six of the world’s top 10 medical schools are in the US, according to QS World University Rankings. The country has some of the world’s most innovative and esteemed hospitals, including the Mayo Clinic, Johns Hopkins, the Cleveland Clinic, and the MD Anderson Cancer center, to name just a few. Industry publication Pharma Exec named six US pharmaceutical companies to its list of the top 10 global biopharma players for 2018. The US National Institutes of Health, with a current annual budget of $37 billion, is the world’s largest biomedical research institution.

On paper, it seems that, if there was anywhere in the world to get good healthcare, it should be the US. So what went wrong?

The market—with its foundations in the World War II-era expansion of employer-sponsored insurance—has produced a system of Haves and Have-nots, where the Haves overspend on bloated healthcare delivery and generally resist structural reforms they perceive as a threat, and a few Have-nots get zero care whatsoever.

Those on the political right decry any government efforts to cover the Have-nots, but, says Feder, “what drives the cost [of healthcare] is not trying to cover the people who don’t have insurance, it’s what we pay for the people who do have coverage.” The Haves drive up spending; the Have-nots bring down key health measures. And actually, so do the Haves, because there is no incentive in the current system to provide good care; the only incentive is to provide lots of care.

Trying to fix the problem from inside the swamp

For his entire adult life, Atul Gawande has been asking why we can’t fix this system. Like many who care about improving the health of Americans, he thought politics was the answer, at first.

In the mid-1980s, he started college at Stanford University, with plans to study medicine, then move back home to Ohio to become a practicing physician, like both of his parents. But at Stanford, he became drawn to the world of politics, and ended up double-majoring in biology and political science.

After graduating in 1987, he went to Oxford University as a Rhodes Scholar, to study for a master’s degree in philosophy, politics, and economics. “I feel I need more background in theory and philosophy before I can go into such areas as medical ethics or research policy,” he told the Stanford student paper at the time. He wrote his master’s thesis on race relations between Indians and the black community in South Africa, and then enrolled in medical school at Harvard University in 1990. He dropped out two years later when Bill Clinton’s presidential campaign called.

Clinton and his team had decided that one plank of his campaign platform would be a promise to solve one of America’s biggest problems: a lack of universal healthcare. At the time, about 17% of Americans didn’t have health insurance, the highest that number had been in over two decades, and there was a sense among pollsters that universal coverage could find the populist support needed to finally usher in changes to a US healthcare system that had become sclerotic.

Beyond the promise of universal coverage, the campaign didn’t have much sense of a plan. Gawande was invited to Little Rock, Arkansas, to help flesh out a program. For his age, Gawande had decent experience in politics. While still in school, he’d been an aide for Al Gore during the then-senator’s 1988 US presidential campaign, and later worked on health issues for Jim Cooper, a Tennessee congressman.

Perhaps Gawande felt at the time, as many did then and many still do, that the problems of public health in America could be solved through the processes of the venerable US democratic republic. It wouldn’t be long, however, before he was unequivocally disabused of this notion.

When he arrived in Little Rock, as Gawande would later recall to the New York Times, Clinton told him he wanted a plan that centered on “managed competition and that he had no interest in a broad-based tax.”

“Managed competition” was a great campaign talking point. The idea, that the government, through regulatory changes, could whip up the necessary market forces to provide universal healthcare, was progressive enough to appeal to the Democrats’ base, but not so progressive as to become a magnet for conservative attacks. Clinton won the Democratic primary and then the general election, unexpectedly beating incumbent George H.W. Bush. Gawande was moved into the role of deputy health-policy adviser for Clinton’s transition team, then made senior health-policy adviser to Donna Shalala, Clinton’s first secretary of health. Gawande was 28.

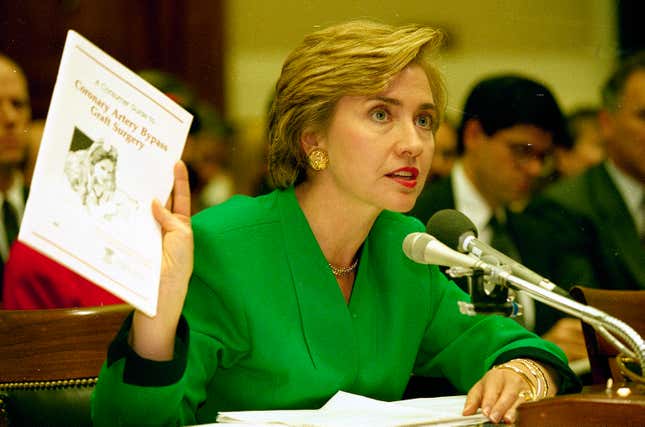

Soon after his inauguration, Clinton announced the formation of the President’s Task Force on National Healthcare, to be led by his wife, Hillary Rodham Clinton. Shalala (who in 2018 ran for and won a seat in the US House of Representatives, as a congresswoman for Florida) was put on the task force, as was Gawande.

Another member of the group, Robert Berenson, a veteran healthcare policy analyst now with the Urban Institute, says the task force was both a management and political mess. Shalala was sidelined by Ira Magaziner, a close confidant of the Clintons who was chosen to lead the task force. Under his leadership, those involved say, the initiative rapidly spun out of control. The team would be up until 2 am deciding on key nuances, only to find out the details had been changed by the time they were presented to the Clintons. The task force’s efforts were also shrouded in secrecy—in some cases, to the point of breaking the law. “When things were getting off track, no one wanted to go to the president to reel it in,” says Berenson, because the task force was the first lady’s project.

By the time the plan was ready for Congress in 1994, the task force had grown to include more than 500 employees, and the document itself had sprawled to 1,342 pages. Insurers and providers bristled at the complexity, and politicians couldn’t fathom how any of it was going to be financially feasible; the task force had specifically been told to defer questions of cost. “Politics was not a major part of our task,” Gawande told the Times in September 1994. “That was what the president and the first lady and their political advisers were supposed to be dealing with. We were there to pull together options for them.”

Georgetown’s Feder, who was also on the task force, says that in order to make the financials work, the plan included a strategy where increases to premiums—the amount of money that an individual or business pays for an insurance policy—would be limited by GDP growth rate. If the market didn’t do that naturally, then payments to providers would be cut to achieve the goal. That, she believes, sank any hope of the Clinton plan becoming law. “That strategy was characterized as expansion of government and as ‘we need to ration.’ The providers and the business community walked away from it at that point.”

It had briefly seemed like innovation was going to come to healthcare through the Clinton White House. Instead, it died in that moment. “The Clintons recognized they needed to get this without disruption,” says Feder. “We thought that’s what we were doing. But it was perceived as highly disruptive.” After the Clinton plan failed, any further effort at reform would be sidelined by the post-9/11 foreign policy wars of the George W. Bush years. US healthcare policy stagnated for nearly a decade.

Gawande decided to go back to medical school at Harvard. “It was an amazing, interesting time,” he told Guernica magazine in 2014. “But when it went down, it went down in flames.”

Gawande sees Obamacare’s biggest mistake

Gawande never went back to politics. He’s been asked why at various points in his career. In 2017 he told Politico that “what I learned…is that what I’m good at is not the same as what people who are good at leading agencies or running for office are really good at. Bill Clinton loved a good fight, he loved a good enemy. I hate a fight. I hate people who hate me.”

In photos and video clips, Gawande looks unassuming, a slight, middle-aged man in conservative suits and ties, conservative eyeglasses, and conservative haircuts. In person, he’s imposing, and taller than you think. In a room full of surgeons, who widely consider themselves the athletes of the medical community, he towers a head above everyone, and has a fluid and controlled grace that stands out. But it’s not just his physicality, it’s also his rhetoric, which is equally fluid and controlled. In conversation with Gawande, others are simultaneously made to feel eminently his equal and deferential to his expertise.

In other words, he’s exactly the rare type who can make people in power, accustomed to getting their way, listen.

Thanks to the popular success of his books and his new, high-profile job in the corporate world, Gawande is now a bona-fide celebrity. For some reason, the American College of Physicians booked his talk at its 2018 conference in a 300-person hall. Ten minutes before the event, in Boston, was set to begin, every seat was filled, and dozens more people were streaming in, while conference staffers muttered and swore under their breath. Gawande had only been talking for about two minutes when murmurs started to rise up from the crowds huddling against the walls on each side of the room, and then a security guard’s voice rose above the din: “Move off the wall,” she said over and over again. Gawande gamely tried to go on, and then someone in the crowd yelled at the security guard to be quiet, and she responded in no uncertain terms: Everyone who didn’t have a seat had to leave, now—or the security team would clear the entire hall.

The crowd erupted and Gawande had to back down. The moderator took over the mic. “We do need to obey Massachusetts law,” he said. As he tried to quell the crowd’s angst, security ushered everyone without a seat out the door. “It’s like a Who concert in 1969,” the moderator joked before handing the mic back to Gawande.

Throughout his talk, called “Slow Ideas: Scaling Surgery,” those remaining in the audience were rapt. No one got up, except for a few people who walked to the front row to take Gawande’s picture as he spoke.

Afterward, Gawande’s handlers allowed him to take a few more photos with fans, autograph a book or two here and a conference program or two there, and then quickly whisked him away. Commanding as his presence his, Gawande comes off as exceedingly humble, even deferential. His first article for The New Yorker, written in 1998, was essentially about a young physician admitting to and trying to process a major mistake he had recently made as a surgical resident. This is not something doctors typically do. As Gawande wrote, “Western medicine is dominated by a single imperative—the quest for machine-like perfection in the delivery of care. From the first day of medical training, it is clear that errors are unacceptable.”

Gawande is quick to point out in public talks and in his writing that his roots are Midwestern. He grew up in Athens, Ohio (pop. 24,000), where his mother still lives (his father died in 2011). Gawande often explains his perspectives by referencing his personal experience living in Anytown, USA.

But it was presumably Washington, DC that taught him that the most expedient path to innovation in healthcare—if there is such a thing—is not through glad-handing and horse-trading. Though there were certainly redeeming qualities about Hillarycare, it was a policy compromise and a shamble in implementation. Years later, there was Obamacare, widely and rightfully lauded as the most important improvement to US healthcare in modern history. And yet, despite the fact that Obamacare has and will likely continue to bring down the untenably high rate of uninsured people in the US, as Gawande notes in a 2017 New Yorker article, “to win passage, the ACA postponed reckoning with our generations-old error of yoking healthcare to our jobs—an error that has made it disastrously difficult to discipline costs and ensure quality, while severing care from our foundational agreement that, when it comes to the most basic needs and burdens of life and liberty, all lives have equal worth.”

This was also the Faustian bargain the Clintons were willing to make back in the 1990s. Gawande has been clear about his thoughts on the subject. As recently as April 2018, just two months before his position at the Amazon/JPMorgan/Berkshire venture was announced, Gawande went on the podcast Freakonomics and said, “The big mistake we have, the thing that’s breaking our back now, is that we’ve tied healthcare coverage to where you work.”

He may, however, have concluded there’s no going back on that deal with the devil, and so the best chance he has is to work to change the system from within. Running an initiative with a stated goal of saving money for some of the world’s wealthiest companies isn’t exactly as high-minded as restoring national aspirations of equality among all men, but if Gawande succeeds in bringing his flavor of innovation to the healthcare systems of Amazon, JPMorgan Chase, and Berkshire Hathaway, he could at the least improve the lives of employees on a pay-scale ranging from minimum-wage Amazon warehouse workers and Dairy Queen servers (Berkshire owns DQ) to c-level executives at the three companies’ headquarters. And if he can truly figure out a way to discipline costs in this sort of corporate environment, while also ensuring quality and satisfying care for patients, all while keeping doctors and other providers happy and engaged—well, then, perhaps he’ll come up with a model that not only gets people out of the labyrinth, but safely across the sea, too.

Everyone wants a health clinic

Private corporations, simply put, have been bad at managing healthcare. “Employers are in the business of their business,” says Galvin. “They have to buy stuff that they use to make the stuff that they are in business for. And almost no part of that supply chain is as complicated or as out of control in its own sector as healthcare.” This mismatch is one reason health insurance has become the most expensive benefit that US employers provide, costing them on average about $5,700 per employee on a single plan and $14,900 for those on a family plan. Premiums and deductibles have skyrocketed, rising 212% between 2008 and 2017 according to the consulting firm Accenture.

A portion of these costs gets passed along to workers directly. For example, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), in 2008, the average US employee on a company-sponsored family plan contributed 26% of the total premium cost. In 2018, that went up to 28%.

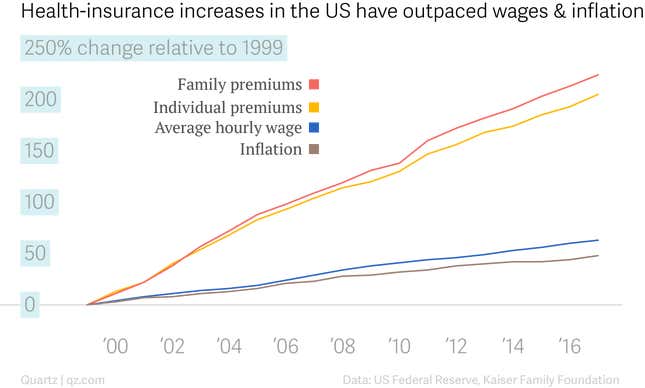

That doesn’t tell the whole story, though. Companies are largely accounting for their increasing healthcare costs by essentially taking it out of employees’ paychecks. It’s “one reason you see flat wages over the past few years,” says Brian Kalis, who leads Accenture’s health consulting arm. Healthcare costs have been rising faster than inflation and much faster than wages: Between 1999 and 2017, hourly wages for the majority of Americans working in the private sector rose about 63% (according Federal Reserve data), while annual premiums rose 205% for single coverage and 224% for family coverage (according to KFF, the Kaiser Family Foundation). Inflation in the same time frame was just 47%.

In other words, all employers have done to deal with the healthcare problems they created 80 years ago has been to shift costs to employees. There’s been little to no innovation. “A lot of what companies are doing here is just benchmarking what others in their industry are doing,” says Galvin. While cafeterias have gone from depressing to Michelin-recommended, and flexible work hours and location have become quotidian, healthcare is at the same “I-guess-this-is-acceptable” level it’s been at for decades. Most people in the US are just happy to have employee-sponsored health insurance of any sort, and if there’s an option between a high-deductible and low-deductible plan, then, well, count your blessings.

The stagnation on coverage benefits is especially shocking because health insurance is, by most accounts, the employee “perk” that matters most to American workers.

In 2018, corporations can no longer afford to be complacent about employee healthcare, because employees are less willing to bear the costs their employers keep trying to offload. The lack of increased wages, combined with a tight labor market and the fact that “employees are paying such high parts of their salary for their healthcare, that they really have not hit before,” says Galvin, means that employers are now “reluctantly facing the fact that they have to deal with this thing we call the ‘delivery system.’”

A number of clear trends are emerging. The most obvious—because it’s the most physically present—is the rise of the onsite (or near-site) clinic. This isn’t complicated; it’s basically a doctor’s office at your office. According to a recent survey undertaken by the New York-based human-resources consulting firm Mercer and the National Association of Worksite Health Centers, 33% of US companies with more than 5,000 employees (the 2015 US census found that 2,050 firms fit this description) provided some sort of onsite health clinic in 2017. That number is up from 24% in 2012. Mid-sized companies, with 500-4,999 employees, are catching up: in 2017, 16% of firms this size (which account for some 17,500 US companies total) offered onsite health clinics, with an additional 8% reporting in the survey that they planned to add a clinic by 2019.

At the most basic level, it’s clear why onsite clinics could offer value to both employers and employees. Instead of taking hours off work to see the doctor, employees can take a five-minute walk across campus, saving the company money in the form of employee time (according to Accenture’s data, Kalis says, absenteeism costs US companies more than $220 billion every year) while for employees the proximity spares them from one of the major known barriers to regular care, especially for chronic health conditions like diabetes or high blood pressure. In theory, it also makes for better employee health. Kalis notes, for example, the no-show rates at on-site clinics is under 5%, “significantly better than you see at traditional offices.”

Crossover Health is one of the most successful new players in this game. Its first client: Apple, which in 2011 contracted the then-little-known startup to run an on-site employee healthcare clinic at its Cupertino, California, headquarters campus. Soon after, Facebook came on as its second client. Crossover has now handled more than 1 million patient visits, and the company recently announced a $113.5 million round of venture funding.

Employers like Facebook (and LinkedIn and Intuit, among others) pay Crossover on a per-member-per-month basis. Employees who opt in use their company-sponsored insurance, with the same copays they’d be looking at for a traditional doctor’s office visit. Crossover’s CEO Scott Shreeve says the per-member payment system means the company’s clinicians don’t have any reason to overbook appointments, or order unnecessary diagnostics, or overprescribe treatment.

Many experts, including Gawande, believe misaligned incentives are the biggest problem of the US healthcare system, which is characterized primarily by a fee-for-service system that leads to volume over value.

Fee-for-service is what it sounds like: healthcare providers are paid a fee for each service they provide. There’s little incentive to provide quality care—just lots of it. It’s a core reason the US has high healthcare costs and poor outcomes.

“If you come in with a shoulder injury and your physical therapist can charge for 12 visits for the injury, how many visits do you think they’re going to charge for?” Shreeve asks rhetorically. “We have data that shows you can get the same outcomes in five or six visits at half the cost and time. That is a great deal. And they go to surgery much less. We can show the same thing with behavioral health visits.”

Other countries with successful healthcare systems utilize fee-for-service models, but “they control costs by having more rational prices; they prevent doctors from becoming entrepreneurs by holding CT scans and PET scans in their offices and doing all that testing for no particular purpose,” Berenson says. And now the willingness of employers to support a system with those kinds of excesses has finally reached a tipping point.

Rob Paczkowski, who manages Google’s healthcare delivery program, says the company decided to run its own on-site clinics “because we are able to sort of control the units of healthcare, control the experience, and control cost, and control the outcomes.” Paczkowski says Google is focused on value-based care, with specific measures for assessing clinics. Though Google wouldn’t go into complete detail, it did offer one example: fertility services.

“We did internal analytics through de-identified claims data…and we found that Googlers using the fertility services were getting some pretty poor outcomes and having a bad user experience and spending a lot of money doing it,” says Paczkowski. Google employees wanting fertility services generally desire pregnancies that result in the birth of a single healthy baby, not multiples. Google contracted with a new fertility-service provider that operated on an outcome-based payment system instead of a fee-for-service system, and, according to Paczkowski, the number of fertility treatment users with multiple births has fallen from 15% to 3% in just two years since the new approach was implemented. “Those multiple births often lead to preterm births, miscarriages, other kinds of bad outcomes,” says Paczkowski. “We’re seeing all those stats come way down compared to our benchmark year.”

What companies like Google and Facebook are realizing, Shreeve says, is that to effectively manage healthcare costs, they need to be directly involved in managing healthcare delivery. It’s only in the last year or so that “for the first time,” Shreeve says, “people are starting to crack open this black box and ask, ‘What’s going on here? We could maybe be involved in fixing this.'”

Gawande, in his 2005 New Yorker article “Piecework” (paywall), writes glowingly about the success of the “Matthew Thornton Health Plan,” an initiative started by a handful of doctors in New Hampshire in the 1970s in an effort to test out an alternative to the fee-for-service standard that existed even back then. The doctors, all with different specialties, paid themselves a fixed salary, and offered services to patients at a fixed fee. “The effect on care was remarkable,” Harris Berman, the doctor who led the initiative, told Gawande. “The urologists, for example, suddenly became interested in having [the general practitioners] understand which patients they really needed to see and which ones we could take care of without them.” Specialists like urologists and ophthalmologists gave the non-specialists training on how to handle basic issues in their specialties—unheard of in the medical world, but in this particular case, they had no problem doing it because they knew they wouldn’t make any extra money if a patient was referred to them. All the incentives clicked right into place.

Today’s employers believe they can bring a similar form of integrated care to their onsite and near-site clinics. For example, says Kalis, “you’ll often see a care manager as part of the team—a specialized care manager or nurse practitioner that coordinates” an individual patient’s care across any number of specialists they might need. This, in theory realigns the incentives for the providers, the employee, and the employer, improving care and reducing overall cost.

It’s likely Gawande will pursue some form of this model at Amazon/JPM/Berkshire. In an investor letter earlier this year, JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon wrote that the new healthcare venture will be built on the concepts of value-based care, including “aligning incentives,” and “studying the extraordinary amount of money spent on waste, administration and fraud costs.” In September, the alliance announced it had hired Jack Stoddard as its chief operating officer. Stoddard is a well-respected old hand in the field; he was one of the founders of Accolade, a startup that helps workers manage their health benefits, and helped lead the team that developed the claims-processing engine Optum, which was later acquired by UnitedHealth. His hiring could be a signal that the initiative will include “a navigation play of some sort resembling Accolade,” says Galvin. Or not. It’s really impossible to tell.

In 2011, Gawande wrote in the New Yorker (paywall) about an experiment in Atlantic City, New Jersey, ongoing since 2007, to improve the healthcare of casino workers through vertically integrated care. Doctors are paid a flat monthly fee for each patient, instead of for individual visits and treatment. Patients get unlimited access, no copay, and no bills, and almost all are assigned a full- time “health coach” whose job is basically to connect with patients and make sure they do what they need to do. “I got a glimpse of how unusual the clinic is when I sat in on the staff meeting it holds each morning to review the medical issues of the patients on the appointment books,” writes Gawande. “There was, for starters, the very existence of the meeting. I had never seen this kind of daily huddle at a doctor’s office.”

The program claims to have reduced emergency room visits and hospital admissions by 40%, and surgeries by 25%, while seeing measurable improvements in patients’ cholesterol, blood pressure, and smoking habits. The program also seems to have saved the healthcare system money: An economist found that casino workers in the Atlantic City program accounted for 25% lower overall healthcare costs than similar casino workers in Las Vegas using standard insurance.

However, it’s not clear a system like this will work for nationwide employers like Amazon, JPMorgan Chase, and Berkshire Hathaway. It’s hard enough to set up a single onsite clinic that can execute a data-driven, managed-care framework; it’d be unprecedented to scale it to hundreds of regions. Consider what happened to the Matthew Thornton Health Plan: As it grew, it was forced to take on more doctors, some of whom eventually pushed back on the standardized salaries. Soon, its integrated care system became untenable. By the 1980s, it had morphed into a standard insurer, and, as Gawande writes, “the experiment was over.”

Can employers fix this?

When I ask Shreeve if we want tech companies to fix healthcare, he says, “To be honest, I want the patient to fix healthcare.” But under America’s healthcare system, patients don’t really have a seat at the table. Maybe, he says, if there were more competition, providers would fix the problems. “But because of the way [the providers] get paid, it feels like someone’s got to come in [from outside] and fix the whole concept. It happens to be that these large employers are involved,” and now, he says, a handful of them “are stepping in to fill a void that I wish wasn’t left by my own profession.”

American workers should be concerned about their employers consolidating control over their healthcare, though. For starters, there are the inevitable privacy concerns that arise when your workplace is also your doctor’s office. But the worries extend beyond that.

Many of the executives running on-site healthcare programs use the term “industrial athlete” to describe the way they’re thinking about providing care to employees: essentially, giving them the full package of integrated health management—nutrition services, physical therapy, diagnostics, treatments—to keep them on the playing field.

The metaphor raises a red flag. When professional athletes are injured, they usually seek out a second opinion from a specialist they pay out of pocket, and who therefore has no financial loyalty to the athlete’s team. But a mid-level marketing manager making $50,000 a year or a factory worker making $25,000 a year likely doesn’t have the money to go outside their insurance plan. If the insurance plan says “you have to see one of the doctors your company has chosen,” it can become cause for concern.

Take, for example, what’s happened at Tesla in the last few months. Elon Musk spent a chunk of time on a Tesla earnings call in late October rhapsodizing about the company’s new health clinics for employees at its car-manufacturing plant in Fremont, California, and its battery-manufacturing “Gigafactory” in Reno, Nevada. Laurie Shelby, the company’s vice president of environmental, safety, and health, chimed in: “We are more than 10% better year-over-year in our lost workdays and our days away,” she said. As Shelby later told Quartz, when she joined Tesla a little over a year ago, she saw problems with the way the company was dealing with onsite occupational healthcare at its car-manufacturing plant in Fremont, California, and its battery-producing “Gigafactory” outside Reno, Nevada. She moved to hire Fremont-based Access Omnicare to come in and revamp the system.

Musk and Shelby’s proclamations about the efficiency of Tesla’s new clinic run by Access Omnicare, however, were shaded deeply by a report published about a week later by Reveal, a publication from the nonprofit Center for Investigative Reporting. In the Nov. 5 article, Reveal alleged that Tesla’s in-house clinics were purposefully “designed to ignore injured workers.” Shelby and Basil Besh, the orthopedic surgeon who owns Access Omnicare and is now both the designer of and primary on-call doctor at Tesla’s Fremont factory clinic, vehemently deny the allegations. “It’s ironic that some of the rhetoric has been that Tesla has been interfering with the care,” says Besh. “I would argue that the entirety of work compensation is [usually] insurance companies interfering with care and Tesla has done quite the opposite, which is get that out of our way and let us care for the patients.”

It’s certainly possible that the allegations are overblown. Tesla and Musk have been magnets for scrutiny; “Every mistake we make is amplified,” Musk said to tech journalist Kara Swisher on her podcast in early November, days before the Reveal article was published. Besh says the new system has “resulted in a healthier workplace [and] happier employees,” and Tesla says it plans to expand its on-site offerings beyond just occupational health, to general care.

In any case, what might matter most for the long-term success of these sorts of programs isn’t their efficacy, but employees’ perceptions of them. Companies also tried an approach to managed care with health maintenance organizations (HMOs) in the 1990s, and that movement failed miserably. Galvin was running GE’s employee health initiative then, and he’s candid about what went wrong. “We did a very logical thing: we said if we use volume purchasing, and get lower discounts by going to hospital A vs. B, and we can make the case that the quality of care is the same or better, we can really do what we do in the other parts of our supply chain.” In other words, GE could make its healthcare purchasing as efficient as the way it purchased raw materials for its factories. “That was the whole commercial HMO movement of the 1990s,” says Galvin. “And we really got our hat handed to us. We did it poorly. We never made the case for quality. And it really wasn’t clear to employees how they would benefit. The second mistake we made was how cultural freedom of choice is in this country, and how absolutely not acceptable it is to restrict that.”

One of the key trends in employer-sponsored healthcare right now has a lot of parallels to the HMO movement: negotiating “bundled payments” with so-called “centers of excellence.” Basically, a company will look at the outcome data across a range of healthcare centers for certain conditions, and choose the one (or handful) that it feels is best. Then, the company will negotiate with that care center to establish a set price to cover the cost of a patient’s care from start to finish for that condition.

Companies ranging from Boeing and General Electric to Lowe’s and Walmart to McKesson and JetBlue have gone down this route. Though providers make less in these bundled systems than they would for the same work in a fee-for-service system, it extends their potential reach and patient base. As for the patients themselves, according to a 2017 Harvard Business Review report, the average Lowe’s employee who had joint-replacement surgery performed at facilities in the company’s center-of-excellence network saved $3,300 compared to those who got the same care elsewhere. The data, according to HBR, also show extremely high patient satisfaction.

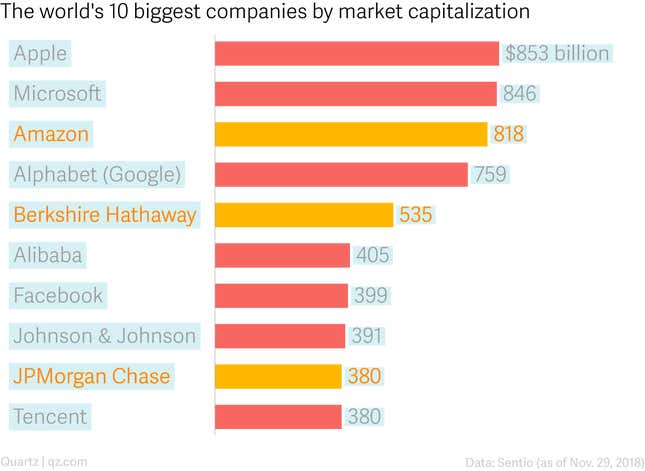

In theory, the Amazon/JPM/Berkshire partnership should be perfectly situated to negotiate these kinds of deals. According to a recent New York Times analysis, consolidation in the healthcare field has led to skyrocketing prices for average hospital stays. After a merger, prices at hospitals go up anywhere from 11% to 54%. The resulting mega-hospitals end up with all of the bargaining chips, which makes it nearly impossible for insurers and employers to negotiate better deals for themselves. Amazon, JPMorgan, and Berkshire, three of the world’s 10 wealthiest companies, with a combined 1.5 million employees and $1.7 trillion in market capitalization as of this writing, may have the weight to pressure providers.

But Berenson isn’t so sure. “They’re spread around the country, so in any given place they can’t have much clout,” says Berenson. “I’m scratching my head about what they’re going to do to have any impact. They have a good brand and they have Atul Gawande who is very smart, but I don’t know what it is they can do to affect the market.” Feder is also a skeptic. “[A]s the concentration of market power of providers grows,” she says, “the best counter to it is the authority of government.”

In the US, however, there’s a deeply embedded resistance to the exercise of the political authority of government, especially when it comes to healthcare. So, as Gawande likely has realized, we’re stuck working within a system where private corporations are perhaps the only entities that can force meaningful change.

Is it all just magical thinking?

One of Gawande’s favorite stories, one he tells over and over in lectures, talks, and written works, is of Francis Moore, one of the most influential surgeons of the 20th century. Moore, in Gawande’s telling, refused to accept the status quo when the status quo was bad, never hesitating to try radical experiments on patients if nothing else worked. There were often failures along the way, but Moore’s rogue work also often led to dramatic advancements in medical science, a list so impressive it’s almost unbelievable: organ transplants, open-heart surgery, the strategy of targeting the endocrine system to treat breast cancer, the extremely basic (it seems in hindsight) discovery that small imbalances in the chemical makeup of medicines actually matter.

“Moore did not hesitate to expose his patients to suffering and death if a new idea made scientific sense to him,” Gawande writes approvingly. We know this is “approvingly” because later on, after recounting how in his gray years, Moore turned conservative in his surgical approach, Gawande asks himself “Which Moore was the better Moore? Strangely, I find that it is the young Moore I miss—the one who would do anything to save those thought beyond saving.”

Gawande’s new bosses—Jeff Bezos, Jamie Dimon, and Warren Buffett—are similarly iconoclastic, willing to break with tradition and disrupt industries in service of their companies. Perhaps they’ll give Gawande the same latitude in healthcare. “I’ll remind people that Jeff Bezos, when he started Amazon, he might have had visions about the ‘everything store,’ but he started with books,” Dimon told CNBC in August. “And he spent 10 years getting books right. So we may spend a bunch of time getting one piece of it right, and testing various things to see what works.”

In his 2004 article “The Bell Curve” (paywall), Gawande retells the story of LeRoy Matthews, a pediatrician who opened a cystic fibrosis treatment center in Cleveland in 1957. By the early 1960s, Matthews was claiming annual mortality rates under 2%, which seemed crazy at the time, when national mortality rates were over 20% and the life expectancy for a baby born with cystic fibrosis was just three years. But over the next half decade or so, data proved Matthews to be a visionary and not a crank. Soon, everyone in the US was using Matthews’ protocols, and by 2003, life expectancy for cystic fibrosis was 33 years. Why, Gawande asks, do we not welcome the type of data-driven innovation that would have led to hundreds of Matthewses?

One reason is that healthcare providers are notoriously secretive and sensitive about data and outcomes. In two early New Yorker articles, “No Mistake” and “The Learning Curve” (both paywalled), Gawande explains that the healthcare system requires doctors to be perfect, leaving no room to admit failure or uncertainty—meaning there’s no room for innovation. “In medicine we are used to confronting failure; all doctors have unforeseen deaths and complications. What we’re not used to is comparing our records of success and failure with those of our peers,” he writes in 2004’s “The Bell Curve.” The truth is we have had no reliable evidence about whether we’re as good as we think we are.”

But Amazon has a sparkling track record of using data to drive down costs while keeping customer satisfaction high. The e-commerce giant may now make most of its profits through its cloud-computing services, but it rose to its current heights by parsing site-behavior data to figure out what customers wanted when, and for how much—and then literally delivering on that. It’s not particularly sexy stuff. But it has made Amazon one of the most admired and trusted brands in America.

Earlier this year, writing in The Nation, economist Stacy Mitchell described Amazon’s goal as “to become the underlying infrastructure that commerce runs on.” Recall that healthcare spending accounts for some 18% of US GDP; it’s not hard to imagine the troika of Bezos, Dimon, and Buffett seeing this whole thing as a sort of incubator for some future healthcare “product” they could roll out nationwide, and which would completely shake up the US healthcare delivery system.

The real monster in the story of Ariadne and Theseus was never the minotaur, of course. He, like so many “monsters” of myth, was only monstrous as a result of human folly. Who knows what Ariadne’s half-brother might have been like if their father hadn’t locked him away in the labyrinth?

It’s useful, too, to remember that once Ariadne’s simple thread suggestion got Theseus through the labyrinth, the problems kept coming.

After Theseus leaves Ariadne on Naxos, he successfully sails home to Athens. But there, he encounters yet another tragedy. Every year, the Athenian ship bearing the human sacrifices to Crete would return flying a black flag to honor their countrymen’s horrific deaths. Before Theseus set sail for Crete, he told his father, King Aegeus, that if he successfully killed the minotaur, he’d return to Athens on a ship flying a white flag instead. But Theseus forgot to change the flags, and his distraught father throws himself off the Acropolis, killing himself.

It’s not clear what caused Theseus’s memory to fail in such an important moment. The most generous readings of the myth say that he never wanted to abandon Ariadne in the first place, but was forced to by the gods. Mired in a deep sadness over having to leave Ariadne behind, he forgot about the flag, inadvertently causing further tragedy.

For all the drama, Theseus’s most significant life achievement was distinctly bland. It came after he took over for his deceased father, and involved no magical weapons, no monsters, no impossible feats of strength. Even the gods, usually ubiquitous in these tales, were absent. And yet, what Theseus did was nothing less than foundational for the entire history of Western democracy: he unified the various demos, or rural settlements, of the Attica Peninsula with the polis of Athens, establishing the political entity that would give rise to what is generally considered the first democracy in recorded history.

Inevitably, corporate America’s effort to meaningfully reform healthcare it will be an experiment, just as the first democracy in Athens was an experiment. “If we knew what to do, JPM/Berkshire/Amazon wouldn’t have said ‘we don’t know what to do,’” says Galvin. They almost certainly wouldn’t have put their new venture in the hands of someone like Gawande—who, for all his experience, has largely worked outside the employer-sponsored healthcare system— and they wouldn’t have given him such a wide berth.

Gawande certainly understands the opportunity before him. “I have devoted my public health career to building scalable solutions for better healthcare delivery that are saving lives, reducing suffering, and eliminating wasteful spending both in the US and across the world,” Gawande said at the time of his appointment. “Now I have the backing of these remarkable organizations to pursue this mission with even greater impact for more than a million people, and in doing so incubate better models of care for all. This work will take time but must be done. The system is broken, and better is possible.”

The promise of better is brilliant in that it serves as both a nonpartisan rallying cry for reform and a plea for patience with the process—two things that have long been missing from America’s healthcare debate. It suggests that expectations ought to be tempered, that perfection isn’t the goal, but improvement is. Better, as Gawande writes in his 2004 book by that title, “does not take genius. It takes diligence. It takes moral clarity. It takes ingenuity. And above all, it takes a willingness to try.”

Correction: A previous version of this story misspelled the name of Crossover CEO Scott Shreeve.