What’s that next dollar worth to you, and what are you giving up to get it?

Imagine leaving on a long vacation during the month of August to go surfing. Longer than the two weeks Americans usually reserve for their honeymoons. Longer than the European summer vacation norm of the entire month. Yes, imagine leaving in August only to return in January.

Imagine leaving on a long vacation during the month of August to go surfing. Longer than the two weeks Americans usually reserve for their honeymoons. Longer than the European summer vacation norm of the entire month. Yes, imagine leaving in August only to return in January.

Every year, Clee Roy does just that. Once his bank account reaches a certain balance, Roy grabs his surfboard and calls it quits for the rest year. He’s not a trust-fund baby, nor a billionaire—he’s an accountant and business consultant in a tiny town on Vancouver Island. What Roy has uncovered is a tiny insight that gives him the freedom to upend the age-old dilemma of work-life balance. He knows how much money is enough.

Roy has calculated how much profit his business needs to generate in a year to cover his living expenses and fund his personal investments. Anything beyond that amount has negligible impact on his life and happiness. As soon as he’s earned that amount, he packs up. Instead of chasing the next dollar, he’s chasing the next wave.

You’ll find Roy’s story, and more about the self-employment philosophy he represents, in Paul Jarvis’ new book, Company of One: Why Staying Small is the Next Big Thing For Business. Jarvis is a veteran internet creator whose work encompasses writing, design, engineering, and creating online courses, including a popular class on how to use Mailchimp. He is himself a company of one, a “solopreneur” who works for himself, and by himself.

Jarvis argues that we’ve walked ourselves into a trap by holding onto two sacrosanct beliefs: 1) bigger is better and 2) growth at all costs. Our insatiable desire for more income may keep us motivated to work longer or to work harder, but it misses a bigger question: What is that next dollar worth to you? And when the answer becomes, “not much,” then why shouldn’t you take a three-month vacation?

But in a culture that deifies startup unicorns and hustle porn and Elon Musk’s five-company quest for world domination, many seem to have overlooked this key question. By internalizing growth at all costs, we’ve lost sight of the fact that bigger isn’t always better—and sometimes it’s measurably worse. Jarvis cites research from the Startup Genome Project showing that 74% of high-growth tech startups failed “because they had scaled too quickly.”

Why entrepreneurs are obsessed with growth anyway

Jarvis doesn’t naively believe that growth is inherently evil, he just cautions against a business mindset that addresses problems by “throwing ‘more’ at them.” ‘More’—whether in time, money, or effort—is often the easiest answer, but not always the smartest one, as it’s usually accompanied by “more complexity, more costs, more responsibilities, and typically more expenses.”

So why do companies grow in the first place? Jarvis offers three economic motivations: inflation (the impetus to maintain the value of your earnings with time), churn (the need to replace old customers with new ones), and investors (who require big payoffs to satisfy their return requirements).

Jarvis also raises another, non-financial motivation, and it cuts to the heart of untethered human ambition: ego.

Human beings are wired to care about what other people think. The college you attended, the car you drive, or the size of the company you founded affect how others perceive you—and therefore how you see yourself. This is part evolutionary (our survivalist needs bind us together as tribes), part cultural (see: the media’s portrayal of success and wealth), part behavioral (heuristics help us categorize people), and even existential (mortality fears can push us to be unreasonably heroic). These influences explain why, at a dinner party, a VP from a tech-startup darling will initially stand out more than an accountant, even if this accountant only works nine months out of the year.

Our egos are at odds with our happiness

Jarvis suggests that our egos set us up for failure—and ultimately unhappiness—by failing to “look at the bigger picture and think about the impact of such growth on our personal lives, or even on the type of work we enjoy doing.”

Which brings us back to the big question: What’s enough money to make you happy?

In a 2010 paper, Nobel Prize-winning economist Daniel Kahneman and economist Angus Deaton (who would win his Nobel a few years later) identified the amount of $75,000 per year as the point at which salary stops having an effect on people’s emotional well-being. But it turns out this doesn’t fully answer the question since a) emotional well-being is not the same thing as happiness (this piece from Vox details why), and b) happiness itself is hard to define.

In 2018, Harvard Business School researchers Michael Norton and Grant E. Donnelly found that wealth “moderately” predicted the happiness of millionaires. They also identified a design flaw in the construction of studies that purport to tell us about wealth and happiness: rich people don’t like filling out surveys.

But what if we swapped research with intuition to create a framework for evaluating what impact the next dollar would have on our happiness? Economists refer to this as “marginal utility” and would argue that it’s subject to the law of diminishing returns. Why? If you’re barely scraping by, doubling your income will markedly impact your life. If you’re Jeff Bezos, doubling your income doesn’t take care of any problem you couldn’t already solve with money.

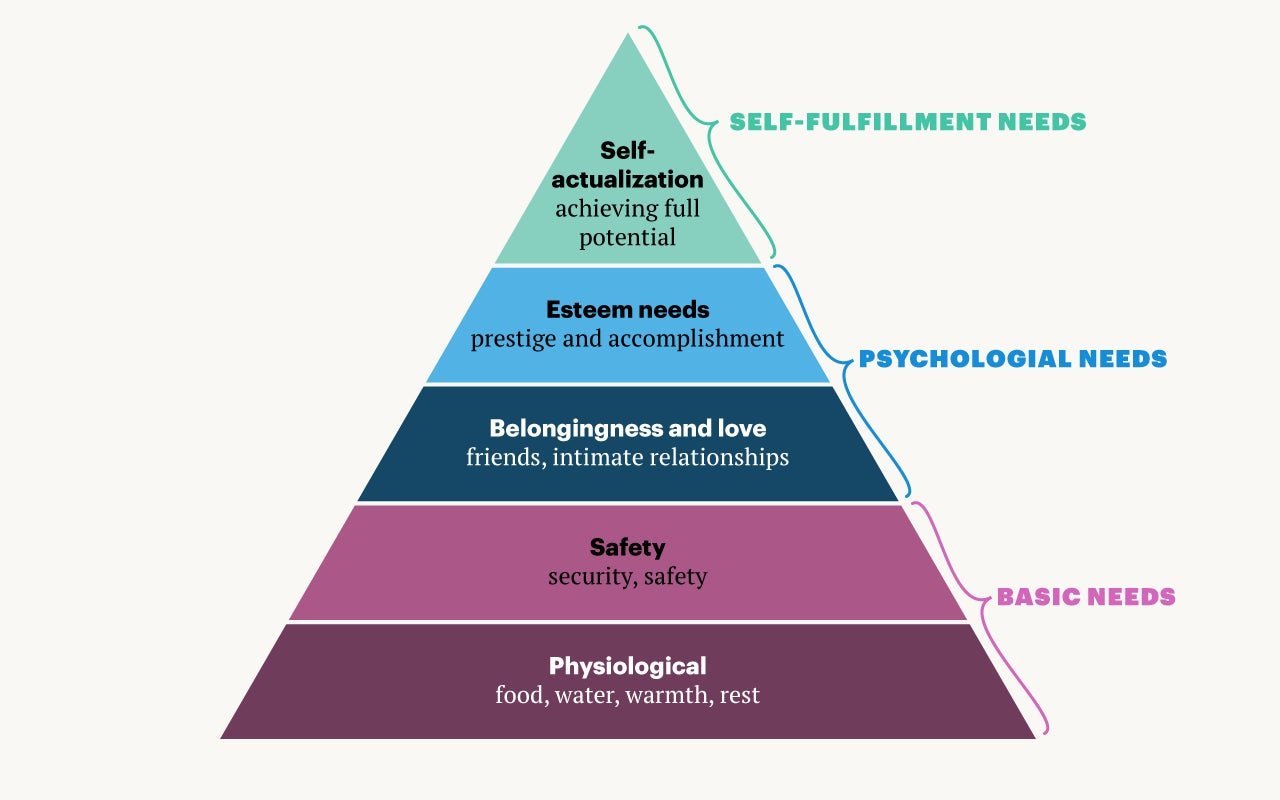

To further understand the diminishing returns of more money, we can turn to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, frequently represented in pop psychology as a pyramid.

By the time you’re talking about the marginal utility of your next dollar earned, you’ve already generated enough income to cover your basic needs, whether physiological (food, water, sleep, shelter) or in terms of safety (i.e. personal, financial, and emotional security). If you’re reading this on your iPhone, chances are you’ve already covered the basics. But can that marginal dollar propel you up the rest of the hierarchy? Does more money improve intimate relationships, feelings of accomplishment, or the ability to achieve one’s potential?

Determining your “enough” amount

As an executive coach, ambitious professionals often come to me in search of their “enough” amount (i.e. when can I go surfing). At that point, they’ve usually already spent many hours reconciling conflicting emotions about their ambition, family life, financial security, and the tip of Maslow’s spear, achieving one’s full potential.

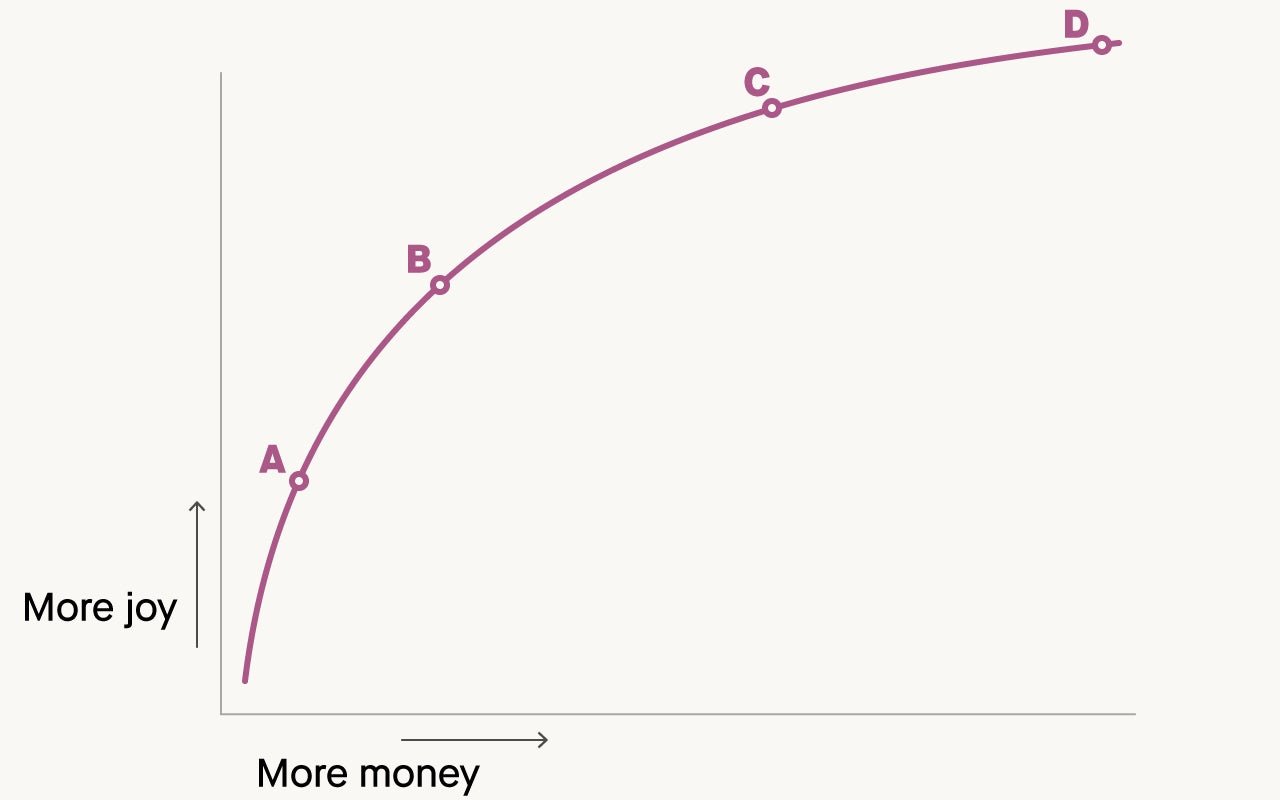

I use a specific exercise to identify what the next dollar is worth to them. It begins with this basic graph below, which intentionally doesn’t have any monetary values on the axes.

Next, I ask them pick which point on the curve best describes their current life situation. Since coaching is very much a luxury good, they’re all past point A; and since they’re all working (either for someone else or as a “company of one”) they’re not yet at point D. Or are they?

Clients at point B see a move to point C as having great potential to improve their living situation, typically with the purchase of a home or the ability to repay debt, support their parents, or save for their kids’ educations.

Clients seeking to move from point C to point D tend to have higher incomes, and are usually seeking more time (and more control over their time). For instance, a partner at a law firm could be close to point D but unable to tap into that potential happiness because she’s rarely free to have dinner with her family and is constantly on conference calls during the weekend.

Vicki Robin, the author of Your Money or Your Life (it’s the de facto bible for the FIRE community focused on financial independence and retiring early) calls this freedom “time sovereignty.” In theory, money can buy you time but ironically in many Western countries, people with higher incomes are likely to spend more time on stressful activities such as commuting and are more likely to agree with statements like, “There are not enough minutes in a day.”

Steering clear of the worst-case scenario

With most people, there’s another powerful force at work, which is the motivation to stay as far away as possible from point A. If you’ve ever struggled to cover your basic needs, you will fight tooth and nail to never return to that way of life. (And if you haven’t experienced this, you still might feel similarly motivated.) This thinking, better known as the scarcity mindset, can transcend basic economics to the point of irrationality.

The scarcity mindset is why 27% of women who earn more than $200,000 a year worry about becoming homeless “bag ladies.” Or why “high wealth retirees” draw down just 17% of their $500,000-plus nest eggs in the first two decades of retirement—terrified of outliving their retirement accounts and ending up destitute, they scrimp on every expense during a phase of life meant to be joyous. Even Silicon Valley entrepreneurs and executives suffer from this mindset. Andrew Taggart, a philosopher who coaches these kinds of high achievers, once told me: “I am beginning to count on my fingers the number of high-powered executives who have mentioned to me their fear of finding themselves in ‘the poorhouse’ someday. (I may have to rent some more fingers.)”

So how can anyone find their enough point? In her book The Soul of Money: Transforming Your Relationship with Money and Life, the activist and philanthropist Lynn Twist reminds us that we’re pretty good at “philosophizing about the great, unanswered questions in life.”

But we need to be looking at our culture’s most “unquestioned answer”: the commonly held belief that money is the solution to most, if not all, of life’s challenges. Maybe then, we’ll understand what’s enough.