An American in Japan is using manga to teach people how to work with foreigners

It’s the intractable problem that has dogged Japanese companies for decades—how do we become more global and less Japanese?

It’s the intractable problem that has dogged Japanese companies for decades—how do we become more global and less Japanese?

The issue is now gaining renewed importance as the number of foreigners moving to Japan to find work grows rapidly (thanks to the Japanese government’s loosening of restrictions on immigration to help alleviate the country’s severe labor shortage) and as cash-rich Japanese companies looking for growth are gobbling up companies overseas at record levels.

In a new book, Rochelle Kopp, a longtime resident of Japan who founded a consulting firm that helps companies with intercultural communication, offers advice for those who might need help navigating the changing Japanese workplace, whether it’s finding the right tone to offer criticism or learning to speak up for yourself. The book, a manga titled How to Work With Foreigners, debuted in February (link in Japanese) by Japanese publisher Shuwa System.

Kopp spoke with Quartz from Tokyo. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Quartz: How did you get into this area of work?

Kopp: I studied Japanese in college, and later came to Tokyo and got a job as one of the few non-Japanese employees of a large Japanese bank, from 1988 to 1990. They were very domestically focused, and suddenly decided to expand all over the world and started to hire foreigners in Japan and didn’t really know how to manage us. That was an absolutely fascinating experience. The non-Japanese also didn’t know how to work for a Japanese company. That was [also] an absolutely fascinating experience. I got very interested in the challenges Japanese companies face as they try to be more global.

Why is your book relevant today?

There’s been a recent wave of hiring non-Japanese employees in Japan. It feels like déjà vu all over again from 30 years ago, but many of the issues are the same.

What has changed from the first wave of hiring non-Japanese in Japan?

In the first wave, the thinking was, “Wow, isn’t this cool, we’re now a big deal and we can spend money, wouldn’t it be fun to be international.” The thinking that “Japan is number one” meant a lot of companies didn’t take (going global) seriously. Now it’s more of a necessity because of the shrinking domestic market. Firms realize if they’re going to have the skills and reach to not be quashed by foreign competitors, they’re going to have to be larger and more present in foreign places. They realize they need non-Japanese employees to work with their foreign customers.

Why did you decide to use manga to teach Japanese about working with foreigners?

Actually it was the publisher’s idea, who said that a very popular genre in Japanese books recently is “learning something through manga.” In the meantime, I had also met a gal who works for Microsoft in Japan, Madoka Chiyoda, who draws manga as her hobby. I had agreed on a set-up with the publisher where the protagonist of the book would be a young female who speaks English but hasn’t worked a lot with foreigners—Madoka was exactly like that. She became the co-author of the book.

Can you sketch out a scenario in the book that illustrate common problems that arise between Japanese and foreigners in the workplace?

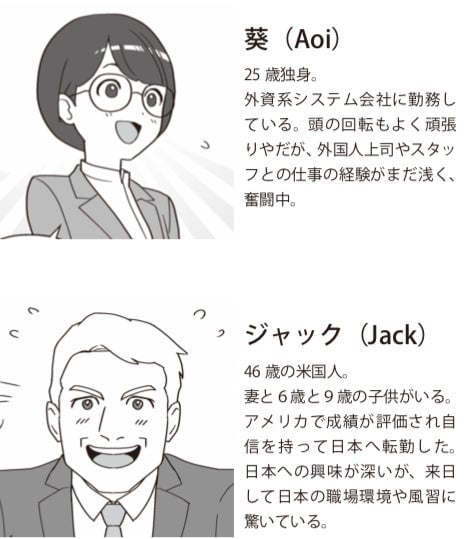

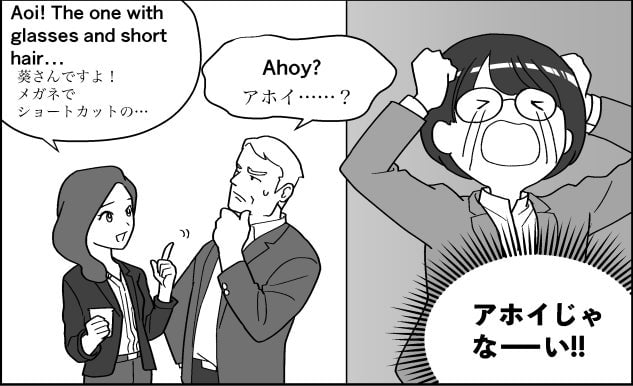

The book follows the story of a 25-year-old protagonist called Aoi, who joins a new department in the Japanese subsidiary of a US company and details her frequent interactions with expats including Jack, a 45-year-old American man. On her first day, she has to introduce herself, and you see her making the typical mistakes people might make with foreigners. She says something very Japanese, “I’m not good enough but I’ll try to do my best,” that doesn’t really translate well in English. She makes such a non-impression that her boss can’t remember her name—one of the running jokes is that he keeps calling her other names throughout the book.

What we recommend is to make sure you say your name really clearly, and if it’s one that might be hard to pronounce, explain it. Then say something about who you are, what your role is or what you have to offer—this is something Japanese generally wouldn’t have to do because it sounds like bragging. The third step is to say something positive like, “I’m really looking forward to working with you.”

Japanese often uses a vague or a slightly positive-sounding phrase to mean “no.” Other cultures demand a clear yes or no answer. Aoi decides she has to be clear and be more specific, so she googles how she should communicate with Americans. The next day in the meeting, she tells an American colleague, “Jack, you are wrong!” and “That’s a lame idea!” She went overboard in the other direction.

What are some of the difficulties in getting Japanese and foreign staff to work together that you’ve seen consistently over the years?

There’s a lot of formality and paying attention to things that perhaps people in other countries don’t think is important. A lot of that has to do with hierarchy and how you treat certain people. The amount of time needed to make decision in a Japanese company is another really big one.

Work-life balance is another issue. A lot of Japanese companies require you to be there right at 9 in the morning. In Silicon Valley, where I’m from, people may have been up hacking until 2am the night before. There’s flexibility there that’s just not even questioned.

Also there’s the question of salaries. Frankly, Japanese are really underpaid in general, they’re locked into a Japanese HR system that doesn’t pay people well. At the same time the company has expats or it’s just trying to get highly skilled labor—which you have to pay market prices for. The whole Carlos Ghosn incident is an excellent example. One of the big issues that fueled resentment (paywall) at Nissan against him was that he made 10 times more than other Japanese executives. It’s a common sticking point.

The Japanese government has been talking a lot about workplace reform in recent years, instituting things such as “Premium Friday” to encourage people to have longer weekends, and encouraging firms to allow flexible working hours. How serious do you think Japan is about changing its work culture?

Premium Friday was just a joke. It was an example of out-of-touch bureaucrats trying to do something. But there is widespread understanding that workplace culture needs to be changed. One of the ways change happens in Japan is through getting widespread awareness of something—having keywords, or ki-wado, is important to help focus people’s attention in Japan. The term hatarakikata kaikaku, or “work-style reform,” for example, has been very effective in building awareness.

Given all these cultural difficulties and differences, what’s driving the recent wave of people moving to Japan to work?

There are a lot of really interesting job opportunities in Japan, particularly for people with technical skills like IT. Japan has a huge need for skilled people. Japan is also a really appealing place to live. A lot of people who come to Japan are also interested in the culture or some specific aspect of it, like martial arts or anime. Those things combined are drawing people despite some of the downsides.