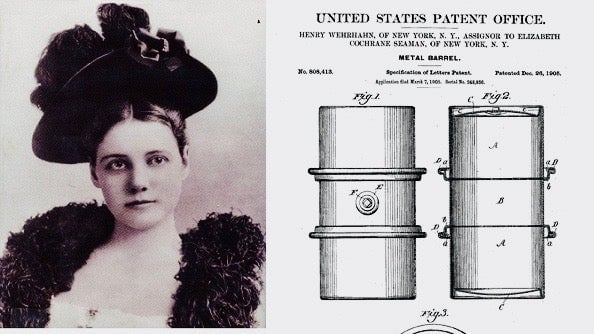

More than a century ago, feminist hero Nellie Bly discovered the key to happiness

Nellie Bly was many things: a fearless reporter, an innovative industrialist, an intrepid world traveler. But her greatest asset, and the one thing that made all her successes possible, is what she wasn’t.

Nellie Bly was many things: a fearless reporter, an innovative industrialist, an intrepid world traveler. But her greatest asset, and the one thing that made all her successes possible, is what she wasn’t.

Throughout her life, Bly—born Elizabeth Jane Cochran 155 years ago on May 5, 1864—refused to be what other people wanted her to be. That trait, some philosophers say, is the key to human happiness, and Bly’s life shows why.

What girls are good for

No one was waiting for Elizabeth Jane Cochran to change the world. In fact, what was expected from girls in her time was that they’d confine themselves to the domestic realm. Her fierce resistance to this expectation is what brought the teenage Cochrane (who added an “e” to her name while in school) to the attention of an editor who would help launch a career that would take her around the globe and make her a household name.

Cochrane was invited to write for The Pittsburgh Dispatch in her late teens after responding to a disparaging article titled “What Girls Are Good For,” which argued they are good only for childrearing and housekeeping. Her passionate, anonymous letter was so impressive that the editor put out an advertisement asking the writer to reveal herself. Upon meeting Cochrane, he set her to work, and thus the writer Nellie Bly was born.

A trailblazer from the start, Bly’s first story, called “The Girl Puzzle,” argued for divorce law reform and won her a full-time job. She went on to investigate the working conditions in factories, infuriating bosses who wrote to her editor to get her to stop. To appease monied readers, he assigned Bly to the lifestyle beat.

Refusing to be relegated to the “women’s pages,” she left for Mexico to be a foreign correspondent. At only 21, determined to do what no other female reporter was doing, Bly wrote about life under the dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz for six months. When she was threatened with arrest, she fled Mexico to New York.

There, the intrepid reporter did her most famous and groundbreaking work, documented in the 1887 series Ten Days in a Mad-House. Bly got herself institutionalized in a New York women’s asylum on Blackwell’s Island for the New York World newspaper. She explained at the beginning of her tale:

ON the 22d of September I was asked by the World if I could have myself committed to one of the asylums for the insane in New York, with a view to writing a plain and unvarnished narrative of the treatment of the patients therein and the methods of management, etc. Did I think I had the courage to go through such an ordeal as the mission would demand? … I said I believed I could. I had some faith in my own ability as an actress and thought I could assume insanity long enough to accomplish any mission intrusted to me. Could I pass a week in the insane ward at Blackwell’s Island? I said I could and I would. And I did.

How to be your own person

From the start of this story, Bly shows she is her “own person,” as defined by Elliot Cohen, editor in chief of the International Journal of Applied Philosophy and a founder of the “philosophical counseling” movement in the US.

In his Psychology Today column “What Would Aristotle Do?,” Cohen considers the nature of existence through a lens of philosophy and literature. Someone who qualifies as their own person, he contends, is independent, authentic, principled, rational, persistent, confident, and courageous in the face of newness.

Cohen argues that being your own person is the key to living a good life. Only someone who isn’t a prisoner to societal conventions and can think independently is able to be free and mentally healthy, he believes. To support this contention, Cohen cites the 19th-century British philosopher John Stuart Mill. “Where, not the person’s own character, but the traditions or customs of other people are the rule of conduct, there is wanting one of the principal ingredients of human happiness, and quite the chief ingredient of individual and social progress,” Mill wrote.

Bly had all the qualities these philosophers describe. Her independence, self-confidence, and courage allowed her to take the asylum assignment. Her authenticity, even while playing a role, helped her get close to her fellow inmates while inside. Her principles and persistence enabled her to write the controversial tale and testify about it later. And her strong character—her personal force and that of her story—were steely enough to prompt social change.

Madness indeed

What Bly uncovered at the asylum was madness, but not on the patients’ part. She wrote about abusive nurses, distracted doctors, harsh conditions, neglect, and the inmates she met. Her work brought attention to an ignored population, institutionalized women, many of whom were not mentally ill but were simply poor, sick, or abandoned by their families. It inspired an official investigation that led to changes in the asylum on Blackwell’s Island and an additional $1 million dollars in appropriations to fund the institution.

Bly innovated a new kind of investigative journalism, insinuating herself among the subjects of her stories, becoming one of them, and revealing to readers things never previously seen in print. In a mad world, Bly’s inherent sanity, her sense of her own self worth and that of others, proved to be a much-needed balance.

Even after the harrowing time on Blackwell’s Island, Bly continued to take undercover roles, posing as other people—a maid, a factory worker–to give her readers a glimpse at the inner workings of their city and the lives of fellow citizens whose stories were rarely told.

Minimalist jetsetting

In 1889, Bly changed her beat. She decided to dash around the globe faster than the fictional character in Jules Vernes’ novel Around the World in 80 Days. And she did it in such minimalist fashion that her travel gear would put tidiness guru Marie Kondo to shame.

To say Bly packed lightly for this epic journey is an understatement. She wore a dress and an overcoat. She had some underwear and toiletries in a small bag carried by hand, and kept currency in a pouch tied around her neck. Along the way, however, Bly did pack up a souvenir—a monkey she purchased in Singapore.

The World sponsored her journey and generated reader interest by holding a competition to guess when she’d arrive at various destinations. But Bly, ever unpredictable, exceeded all expectations.

The speedy traveler made it around the world in 72 days, traveling by steamship and rail from the US to Europe, through the Middle East, and Asia, and back to New Jersey. Bly beat not only the fictional record of 80 days set by Jules Verne but also a competing reporter sent around the globe by Cosmopolitan magazine, who completed the journey four days later.

For her part, Bly claimed she wasn’t racing. Even when she won the competition, she made it a point to be unconcerned with goals that were not her own. She competed only with herself.

Another act

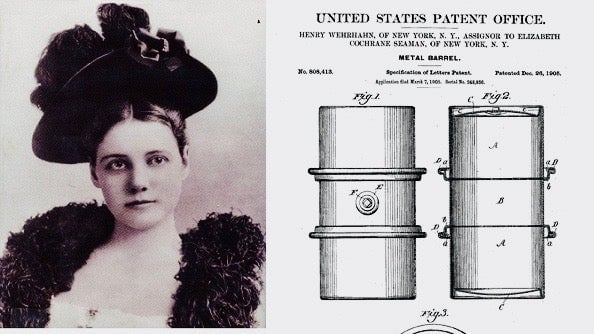

In the early 20th century, Bly successfully challenged convention again. She totally transformed. The former reporter began running the Iron Clad Manufacturing Company—maker of enamel ware, cans, boilers, and tanks—which she inherited upon the death of her husband, Robert Seaman. With this, Bly went from chronicler of the worker’s plight to the only female industrialist of her kind at the time. To work at her factory meant being employed by a champion of the people and a boss unlike any other.

Aptly, the woman with a will of steel innovated using the same material of her spirit. She invented a new type of container, a barrel made of steel, an oil drum that could not leak. In her words, “I finally worked out the steel package to perfection, patented the design, put it on the market and taught the American public to use the steel barrel.”

So it turns out Bly, who inspired the character of the intrepid reporter Lois Lane in Superman, was also a pivotal figure in the history of the American petroleum industry, according to the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. She’s been the subject of numerous books, plays, televisions shows, and documentaries, and remains a relevant and influential figure nearly a century after her death of pneumonia in 1922.

But the reason to admire Bly is not these accomplishments alone, which are merely byproducts of her most impressive trait. Her greatness was that she knew what was right for her even when society disagreed. She was firm in her conviction and confident in her abilities, gathering fans even as she criticized a culture that tried to stifle her.

During World War I, Bly returned to reporting. She covered the men fighting on the fronts in Europe and at home, and wrote about the suffragettes’ fight for women’s right to vote. She died only two years after women in the US finally won that right to cast their ballots. Yet her life was more adventurous and independent than those of many contemporary feminists who have benefitted from her efforts.

She’s a hero for all times, and her remarkable tale is a reminder that to be a real success, in the truest sense, means insisting on being your own person.