How the NFL separates good from great when evaluating talent

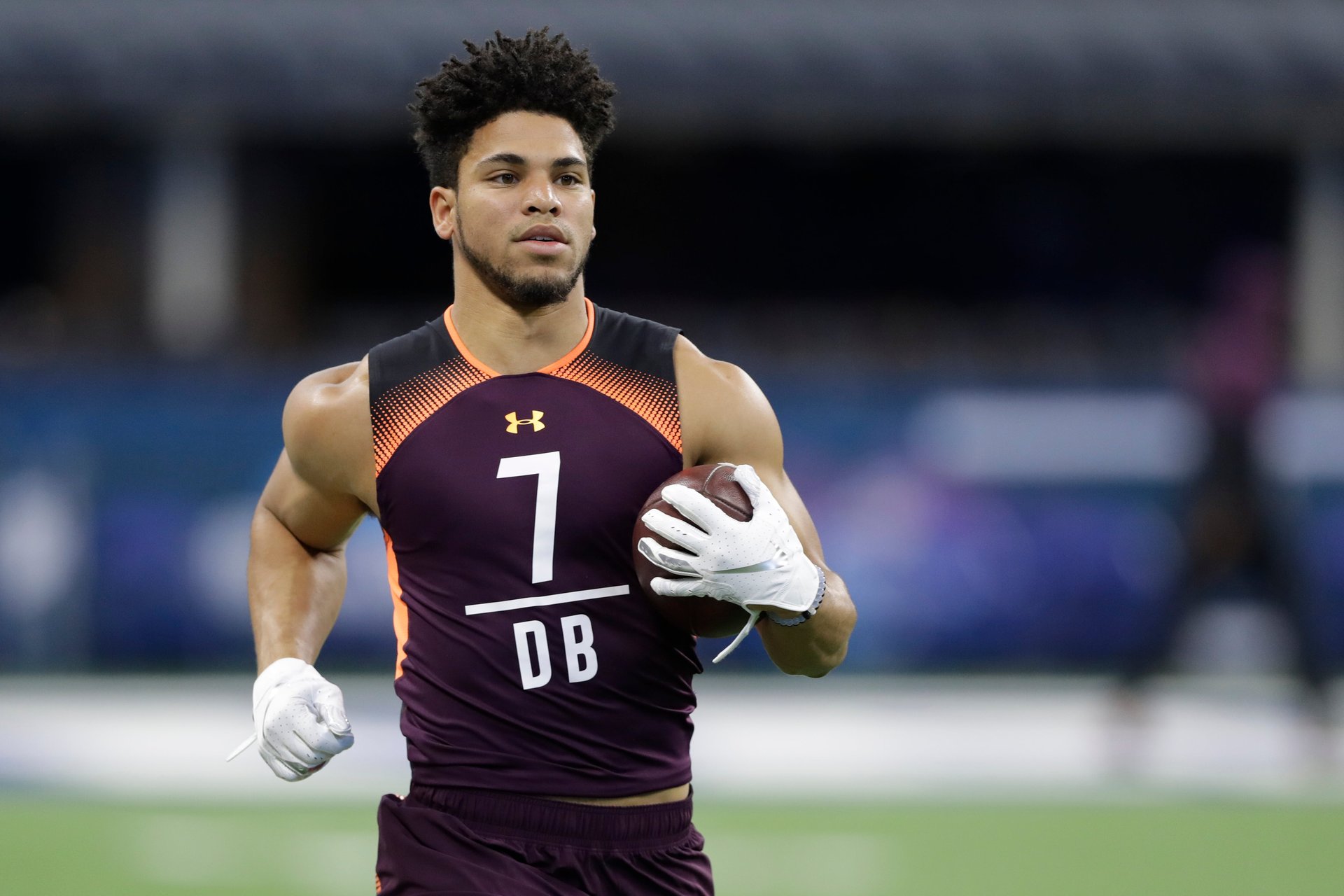

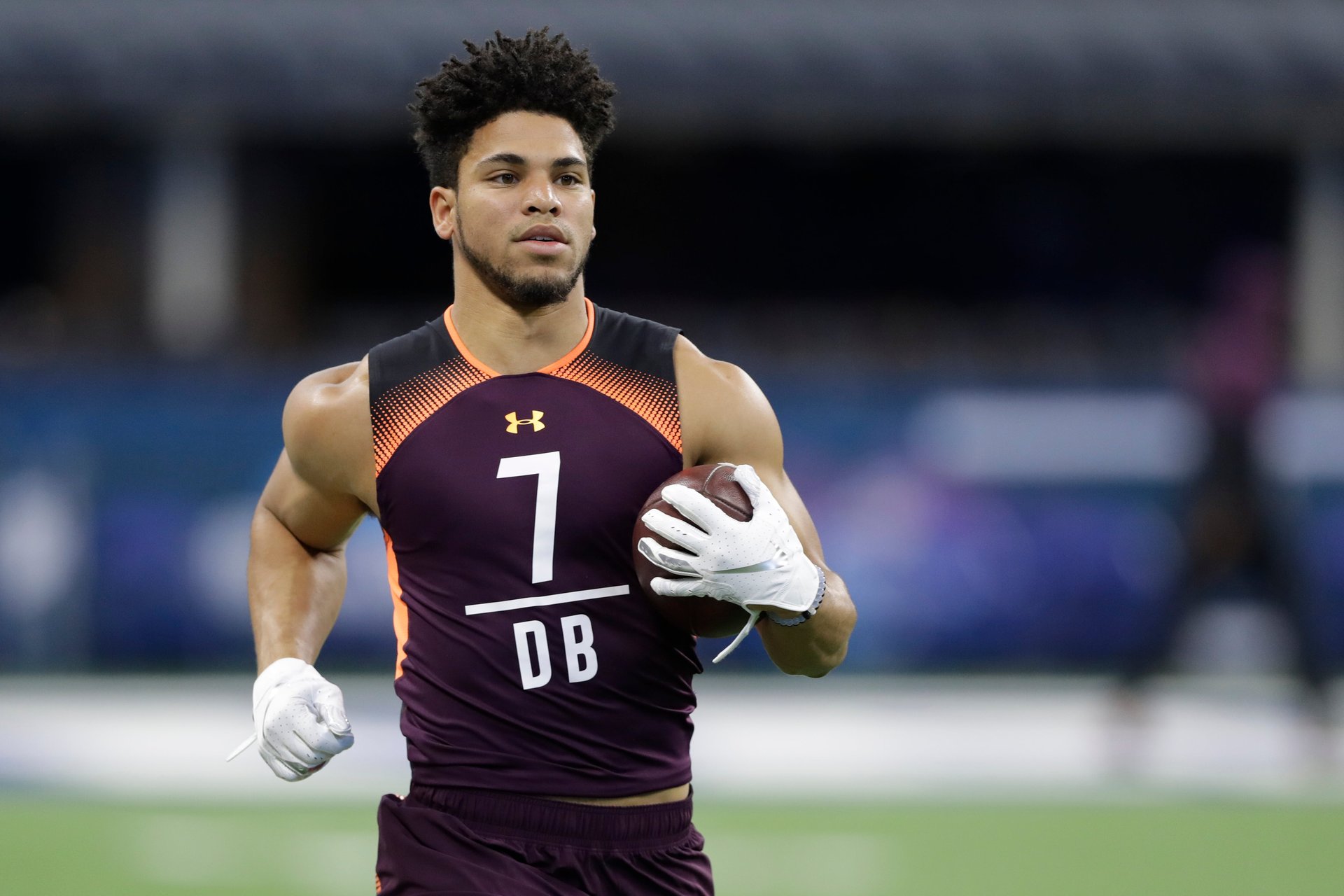

Lucas Oil Stadium in Indianapolis seats 67,000, but on a Monday morning in March, the stands were mostly empty—save for a collection of scouts and coaches scattered about the cavernous arena. On the field, Jordan Brown toed the starting line of a 40-yard stretch of artificial turf. He took his time as he settled into a sprinter’s stance. He knew the next five seconds could define his future.

Lucas Oil Stadium in Indianapolis seats 67,000, but on a Monday morning in March, the stands were mostly empty—save for a collection of scouts and coaches scattered about the cavernous arena. On the field, Jordan Brown toed the starting line of a 40-yard stretch of artificial turf. He took his time as he settled into a sprinter’s stance. He knew the next five seconds could define his future.

Brown, a self-assured 23-year old from Phoenix, was one of 337 college juniors and seniors invited to the National Football League’s annual Scouting Combine. The event, now in its third decade, is an annual audition for would-be professional football players who spend four days being weighed, measured, probed, and tested in front of their 32 prospective employers.

For players who were stars at big-time college football factories, the combine can be a formality. Some use it to cement their position in the upper rounds of the following month’s NFL draft, while others, sensing their stock can only fall with an average performance, will skip certain drills.

But for prospects like Brown, an unknown player from a small school, a strong performance at the March combine is critical to being drafted, the first step toward a career in football.

Brown had already beaten the odds by making it this far. A high school wide receiver with middling speed, he hadn’t been thought of as much of a college prospect. He accepted the only scholarship offer he received, to play at South Dakota State in the second tier of college football. Brown flourished, though, after switching to cornerback, the position for lean, speedy defenders who cover wide receivers. By his junior year in South Dakota he was was on the radar of scouting services employed by the NFL. After his senior season he was signed by an agent and invited to the combine.

Like many students preparing to leave college, Brown was seeking to nail down a job offer from a big, well-known employer. But few entry-level job candidates are subjected to the same level of scrutiny as NFL prospects. While Goldman Sachs asks its recruits to take a personality test and big tech companies quiz job candidates on how well they solve programing challenges, the NFL probes deeper. It puts players through a battery of drills, and measures them off the field, too. Players at the combine endure MRI scans, get examined by physicians, puzzle through intelligence tests, and undergo background checks. And that’s after the scouts have interviewed high school and college coaches to assess a prospect’s personality, or “make up” in coach-speak, and probe for possible character defects.

Brown spent all of January and February training for the combine, and especially for the 40-yard dash, one of the most critical elements of the tryout.

Forty yards is an arbitrary distance to measure the speed of a football player, and for linemen and quarterbacks, it’s farther than most will ever sprint in a game. But for aspiring professional cornerbacks, a fast 40-yard time is critical, as important to entering the NFL as a dazzling LSAT score is to entering Yale Law School. It won’t guarantee success, but it will get you in the door.

The NFL combine record for 40 yards in 4.22 seconds was set in 2017 by wide receiver John Ross. Jaire Alexander, the first cornerback drafted last year, ran it in 4.38. Brown ran 4.46 a few weeks before the combine, and hoped to match that speed in Indianapolis. Prior to the combine, he was confident. “I’ve been waiting my whole life to be on this stage,” he told me. “I’m prepared.”

But after a false start that appeared to rattle him, Brown ran just 4.53 in his first attempt. On his second and final attempt, he improved his time slightly to 4.51. That tied him for 28th among the defensive backs—both cornerbacks and safeties—who ran that morning, and placed him in the 46th percentile among all cornerbacks with recorded 40 times at the combine dating to 1999, according to the player-analysis site MockDraftable.com.

Brown had some advantages over his competition—at 6 feet, he was taller than average for his position, and could leap higher—but without a blazing 40 time, his path to the NFL just got harder.

Like most industries, pro football’s system of talent evaluation has evolved with advances in technology. Scouts were once required to travel to colleges watch prospects in person, dramatically limiting the number of players evaluated. They would lug reel-to-reel projectors with them to watch film kept by the university’s coaches. Film gave way to video tapes which were replaced by digital files. Scouts can now watch footage of hundreds of players, and quickly edit it into easily digestible packages for the rest of the organization.

Despite the embrace of digital technology, pro football remains stubbornly analog. As with baseball before it, analytics has come to football, and teams are using statistics to make smarter and more nuanced evaluations. But coaches still want to see players in person, look them in the eye, and measure them by hand. Even then, teams remain skeptical about the value of the hard data they obtain. “It’s never going to be scientific,” one NFL executive said. “You’re never going to be able to just plug in the numbers. Ultimately it comes down to a feel for the guy and whether he’s a fit for your team.”

That sets pro football apart from the current thinking in most other industries about how to evaluate and assess talent. Big employers like Google and Unilever are trying to systematize the process as much as possible, to eliminate hiring bias and to ensure prospects are evaluated only on the background and attributes relevant for the job. In early stages, some employers will obscure applicants’ name, gender, or alma mater, to guard against that information coloring the judgment of hiring managers. Increasingly, job postings are being scrubbed of language that paints a portrait of a particular type of candidate rather than the particular skill set desired, and job candidates are increasingly finding themselves interviewed by diverse panels and asked standardized questions, designed to remove as much variation from the process as possible.

In the NFL, teams start preparing for the draft a year in advance, with the names of the approximately 16,000 college players eligible for the draft. The master list is assembled during the players’ junior year by scouting services—most NFL teams subscribe to one of two services—who also offer preliminary evaluations of the top 10% or so of all college players, the ones who might have a chance of being drafted. Teams then build on those evaluations with their own scouting, which includes watching college games and practices as well as talking to coaches about the players’ character and leadership potential.

Of critical importance is a player’s injury history. Nothing scares off teams like a lingering injury, and the challenge of getting accurate information about player injuries was the original catalyst for the NFL combine. In the mid 1970s, teams began performing their own physicals on players; but eventually it was deemed impractical for college seniors to fly out to two dozen teams for physicals, and a few scouting services began holding camps. They were combined —hence “combine”—in 1985, and a few years later Indianapolis became the event’s regular host city.

Sussing out injuries remains the most essential function of the combine, and while it doesn’t make for compelling television, reliable medical history is the data hardest to come by from any other source.

Before they take part in any drills, NFL prospects are weighed and measured, then subject to a battery of medical exams. Brown describes wearing nothing but tight compression shorts in a ball room at the Indianapolis convention center, where an examination table was set up in the center of a U-shaped arrangement of tables.

Brown injured a knee in high school and mangled a finger in college. After his name and injury history were announced, he said, “people from around the room would come up and kind of yank on everything.” The examination, he said, lasted 10 or 15 minutes before he was moved to another room, where the process was a repeated. “I did that in seven different rooms,” he said.

The NFL doesn’t televise the medical exams. Given the optics of hundreds of young, nearly-naked, mostly black men being probed by phalanxes of mostly white doctors, that’s probably in the league’s best interest.

As a high school senior, Brown had little reason to think he would ever make it to an NFL combine. His first love was basketball—his father was an assistant coach on his high school team—and although he played football, his team struggled. He also was slow for a college prospect, running the 40 back then in 4.7 seconds, which he now attributes to being relatively thin. (Brown gained almost 40 lbs in college and weighed 201 lbs at the combine.) But he could catch the ball, and set state high school records, which helped bring him to the attention of a South Dakota State University coach tasked with recruiting in Arizona.

Brown was the type of player that sustains schools like SDSU, which plays in the Missouri Valley Conference of the NCAA football championship subdivision (formerly known as Division I-AA). Teams in this tier are limited to 63 scholarships (instead of the 85 allowed at the highest level) and they don’t play in the year-end bowl games like marquee schools, but instead compete in a 24-team playoff.

While elite football programs are looking for a finished package, a school like SDSU needs to take chances on rawer prospects, said Dan Jackson, the team’s recruiting coordinator. Brown was tall and thin, with a frame that could fill out, Jackson said. Plus, he could play. “The reason why we liked him was his fluidity,” he said. “On film, he never got caught.”

With no other scholarship offers from four-year schools, Brown visited SDSU in Brookings, a prairie town of 22,000 that is 92% white. Initially, Brown was reluctant to move from Phoenix.

“My senior year in high school we went for a visit and it was super cold, and the culture there is different,” he said. “I said, ‘Mom, I don’t know if I can do this,’ and she was like, ‘Well they’re going to pay for your school so we really have no options.’ And I was like, ‘Alright, I’m going.’ So I committed to them right there on the spot.”

While Brown entered SDSU as a wide receiver, he was quickly converted to the secondary as a cornerback. He sat out his freshman year as a redshirt, then quickly established himself first as a starter, then as a star. By his senior year, he was a team captain and feared by opposing teams.

“I’ve never been a part of anything that dominant in the secondary,” said Jackson. “It was like the whole stadium knew that if they threw it at Jordan, it was going to be a big play” for SDSU.

At the end of his senior season, Brown led the Jackrabbits to the semi-finals of the Football Championship playoffs. He was also on track to graduate with a degree in hospitality management, following in the path of his mother, a revenue manager for a Hyatt hotel.

Named first-team All-America, a career in the NFL began to at least seem possible, an option that solidified after he was one of 114 players invited to the Senior Bowl, a showcase for pro prospects, in December.

Brown first came to the attention of Jason Bernstein his senior year at in South Dakota. Bernstein, a sports agent who runs a small firm, relies on a network of scouts to tip him off about talented players at small schools. While big agencies like CAA represent the no-doubt stars, Bernstein and his agency, Clarity Sports, survive by finding undiscovered talent.

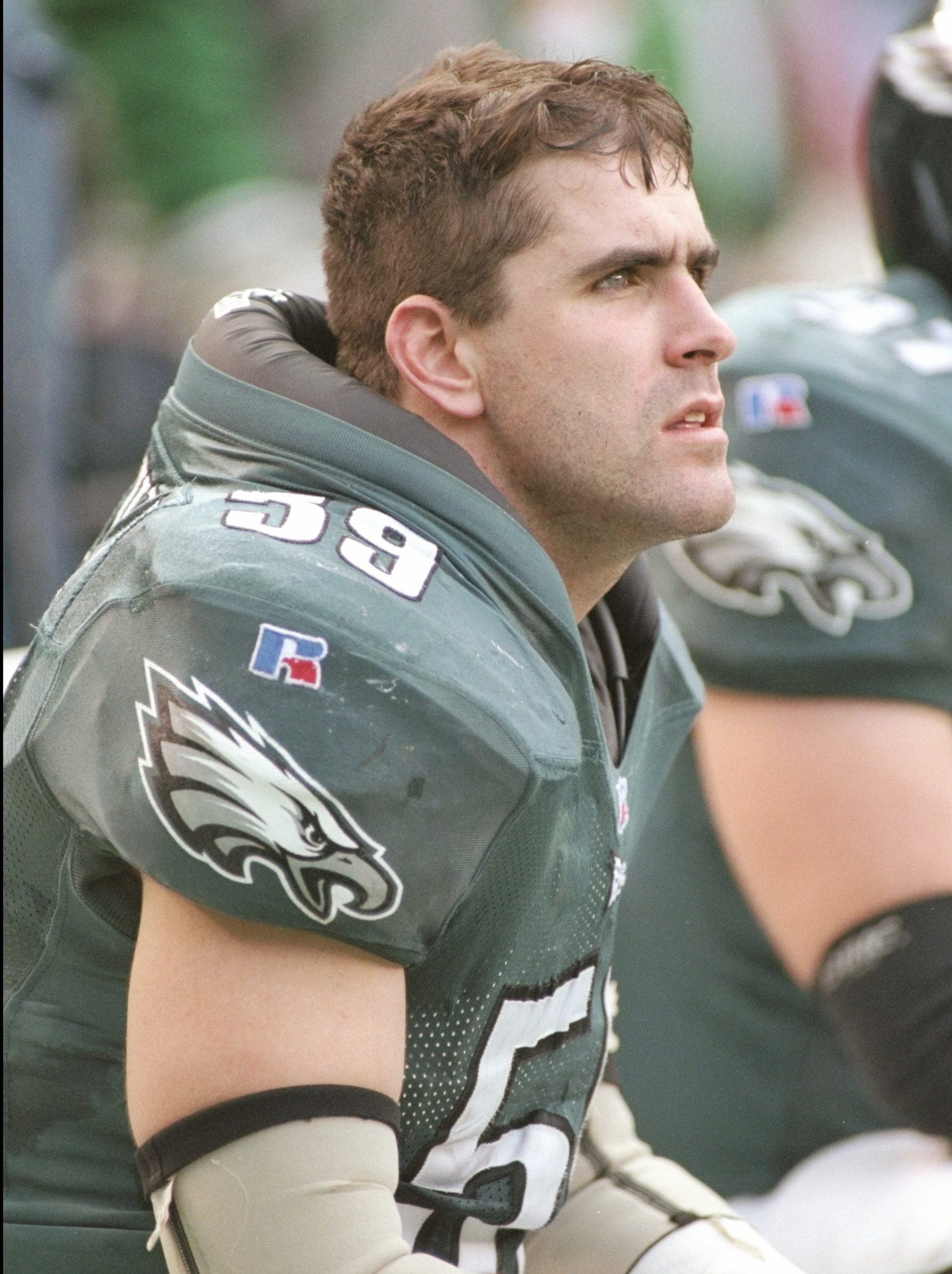

In its early years, the combine was intended to measure raw ability. Players would show up in whatever shape they were in two months after the season and run through the drills. It was, in theory, an even playing field. But that was before Mike Mamula.

Mamula was a defensive end who had a respectable if unspectacular college career at Boston College. But he spent the months before the 1995 combine training for its specific set of tests and drills, and delivered a jaw-dropping performance. He bench-pressed as much weight as the bulkiest offensive lineman, out-jumped players much lighter, and ran 4.62 in the 40-yard dash, an extraordinary time for a player weighing 252 lbs. Mamula, previously regarded as a mid-round pick, rocketed up the rankings of NFL scouts and was drafted seventh overall by the Eagles, who traded up to snag him.

Mamula had a solid pro career cut short by injuries, but his greater impact was in helping reframe how players approached the draft. It became clear a prospect could dramatically improve his draft position through a stand-out performance at the combine, giving players enormous incentive to train feverishly in the two months after the end of the college season. “The combine is a test the NFL lets you cheat on, because you know all the questions before you take it,” Mamula’s fitness coach, Mike Boyle, told Sports Illustrated in 1995. “And yet few people take advantage of that.”

Mamula’s hack of the combine gave rise to a highly specialized micro-industry, to prepare prospects for the annual event. Like test prep classes for the SAT or GMAT, combine training centers work to shore up weaknesses and enhance the strengths of the few hundred prospects invited to the draft.

Brown had gone home to Phoenix to train with EXOS, one of the bigger players in the sports training world. After eight weeks of preparation, he was pleased with his results. Much of his work had been on honing his sprinters’ start in the 40, and three weeks before the combine he ran a 4.46 in training.

Bernstein was optimistic, too. He believed a third-round selection was a possibility for Brown, a view shared by the NFL’s own scouts, although he thought a fourth- or fifth-round selection was more realistic. Few players are drafted as high as they think they should be, Bernstein said. “You try to lower expectations, but you hope for the best.”

In its one concession to the live fan experience, the combine displays the bench press test in front of an audience in the Indianapolis convention center. Die-hard NFL fans and high school football teams from the region are ushered into a convention center ballroom, where they are first primed with exhibits showing off the Vince Lombardi Trophy, given annually to the Super Bowl winner, and the gaudy, diamond-encrusted rings the winning teams award themselves.

For better or worse, though, Brown’s 40 time hangs over him. Despite the disappointment, he soldiers on through the rest of the days drills, and to the untrained eye, looks as skilled and determined as the other defensive backs.

After the combine, Brown returned to South Dakota, where he continued training for the school’s on-campus “pro day,” an opportunity for scouts to interview, time, and measure players not invited to the combine, or, as in the case of Brown, to get a second look. In between workouts, he took an online class in human resources—a prerequisite for his hospitality management degree—and read motivational books like Relentless by Tim Grover, the trainer for Michael Jordan and Kobe Bryant, and an autobiography of radio host Charlamagne Tha God.

SDSU’s pro day on March 29 was attended by about 25 pro scouts, and Brown improved his 40-yard time to 4.44. With just a few weeks until the draft, he hoped it was enough to convince teams he was ready for the NFL.

Like many American businesses, professional football depends on a steady flow of talent from universities to sustain its workforce. But unlike other highly sought-after employers like Apple or Goldman Sachs, the NFL maintains a virtual monopoly on its industry’s employment opportunities. Marginal players may wind up toiling in Canada or the Arena Football League, but they’re all trying to get to the NFL. And while Google may look forward to decades of productivity from its hires, the NFL churns through its workers at an alarming rate. The average career length is just 2.7 years, cut short by injuries and fear of brain damage, according to a 2016 analysis. Replenishing the talent is an NFL imperative.

Teams go to these lengths because the stakes are high—pro football is a zero-sum competition, where every team’s victory is another team’s defeat—and the executives of losing teams are regularly cashiered. It is an industry where every manager, every season, is highly incentivized to pick the right mix of talent for their organization.

The draft began in 1936, 16 years after the NFL’s founding. Its purpose then, as now, was to distribute talent evenly throughout the league, so the richest clubs wouldn’t be able to scoop up the best players. In its early years, the draft was a low-key event, and many players were unaware they were drafted, or much cared. The first pick of the inaugural draft, Heisman Trophy winner Jay Berwanger of the University of Chicago, opted not to play pro football at all, and instead became a foam rubber salesman.

As with most things in the NFL, the draft is now a gargantuan television extravaganza. Spread over three days, it’s held in stadiums and or closed-off downtowns, as this year’s was in Nashville, Tennessee, with tens of thousands of fans cheering (or booing) their teams’ selections. The basic premise is unchanged since the 1930s: Teams take turns selecting players, who can only sign with that franchise, at a wage scale prescribed by the NFL’s union contract.

The first round of the draft takes place on a Thursday night. The most likely picks have been invited to the host city, and they appear on stage after their name is called. The second and third rounds take place the next night, and the remaining four rounds take place in a relatively brisk few hours on Saturday.

Brown watched the draft’s final rounds at a small party at the home of his girlfriend in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, with college teammates as well as friends and family who traveled from Phoenix and Omaha, Nebraska, for the occasion. He still hoped to go in the fourth round, but as the draft unspooled, his name wasn’t called, and Brown began to grow anxious as other cornerbacks he had competed against at the combine were selected. The fourth round slipped into the fifth, and the sixth.

Still, Brown was bewildered that he fell so far. “There was 29 corners picked ahead of me,” he said. “I was supposed to be the 15th-ranked corner. Every team passed on me for seven rounds. I was super shocked that things didn’t go as planned.”

Of all the various draft scenarios Brown and Bernstein had considered, the team that took him seemed a remote possibility. Brown said he interviewed with almost every team prior to the draft. The Bengals were one of the few he didn’t talk to.

Duke Tobin, head of player personnel for the Bengals, said the team had its eye on Brown since the summer before his senior year, when the team’s scout responsible for the upper US midwest first took note of Brown and watched video of his plays. That fall, the scout visited SDSU and watch practice and games, talking to coaches about his potential.

Bengals scouts also do preliminary background checks on players, reading articles and trying to get a fix on his personality. Coaches want players who are positive additions to a locker room, and not all players will fit into every team.

During Brown’s senior season, the Bengals’ area scout wrote up a full report and entered him into the team’s database of thousand of players. He was scouted again at the Senior Bowl, and the Bengals took note of how he performed against more established players.

The combine reinforced the team’s perception of Brown as a solid, productive player, Tobin said, and his 40 time wasn’t a black mark. The Bengals also liked his record of accomplishment in college, and his role as team captain.

About a month before the draft, the Bengals’ scouts and player personnel met to finalize their grades on all the players they considered draftable, about 500 in all. By now, five or six of the scouts had evaluated Brown, either in person or on tape. The team included him in its rankings of all the cornerbacks they would consider drafting.

Late August in Cincinnati does not feel like football season. On a sultry summer evening evening in the Ohio Valley, a torpor hung over a nearly empty Paul Brown Stadium as the Bengals hosted the Indianapolis Colts in a meaningless exhibition game. Before kickoff, the Ben-Gals cheerleading squad performed, and finished to no applause.

It was the fourth, and final, preseason game before the start of the regular season; the primary motivation for both teams was to prevent injuries at all costs. Most starters were benched, and even the most critical backups would not see action. Instead, the game would be contested by players on the fringes of the roster, looking for one last chance to impress coaches and make the team.

NFL teams can invite 90 players to training camp—drafted and undrafted rookies, free agents, and returning veterans—but need to trim that roster to 53 prior to the season. While injuries would takes their toll, the math was unavoidable: A great many healthy players would not make the squad.

Brown was drafted into a Bengals organization in flux. After a 6-10 season in 2018, head coach Marvin Lewis, 61, was fired after 16 seasons as head coach, one of the longest tenures in the league. The Bengals had a long, established tradition of mediocrity, and Lewis’s replacement, the boyish Zac Taylor, a 36-year-old first-time head coach, was charged with injecting new life into the team.

Logic holds that the poorer a team’s performance the previous year, the more opportunity there is for new players. It’s a lot harder to crack the roster of a team with a winning formula than one searching for answers. And a new coach might not be wedded to players held over from the previous regime.

Yet the one position where the Bengals seemed most secure after 2018 was in its defensive backfield, where Brown played. The unit was viewed as stable and dependable. While there were some injuries, none of the reporters and blogs that track the team suggested that bulking up the secondary was a pressing need for the team prior to the draft.

As a result, Brown had trouble finding playing time in the first three pre-season games. The team had 11 cornerbacks on its pre-season roster, but would likely only carry five or six in the regular season. Heading into the final pre-season game, against the Colts, Brown was listed as the fifth option at right cornerback.

The most optimistic outcome for Brown was making the roster as a backup who could contribute on special teams, covering punts and kickoffs. A less attractive option would be winding up on the practice team, sometimes called the taxi squad, a group of 10 players that can add depth in practice, but aren’t eligible to play. Even being cut outright wouldn’t necessarily end Brown’s NFL dreams, since another team could sign him to their roster or practice team.

Brown knew his odds weren’t good, but embraced the opportunity and looked for chances to shine. “Every day is a like a job interview for a rookie,” he said. “It’s definitely nerve-wracking.”

Prior to the Colts game, reporters who covered the team thought Brown should see a lot of action. Failing that, it would be a good sign if he didn’t play at all, which meant the team wanted to hide him from other teams’ scouts. The worst case scenario was if he only played in the fourth quarter, in mop up-duty.

Brown didn’t start the game, and didn’t appear at all in the first half. It wasn’t until, with 5:38 remaining in the third quarter, he was put in to play, after teammate DaVontae Harris left with an injury. Brown then played intermittently for the rest of the game, appearing on the kickoff team and covering the Colts’ wide receivers. He made a few tackles and avoided making any significant mistakes, but he also didn’t get a chance to make the sort of eye-grabbing play—swatting down a sure touchdown pass, snaring an interception—that could elevate him above his competition. The game, mostly languid, was briefly interesting at the end but finished with a 13-6 Colts win.

In the Bengals’ vast locker room after the game, Taylor, the head coach, was almost apologetic when asked about Brown, acknowledging his days in Cincinnati might be numbered, without saying as much. “He’s a smart kid, and does it the way you want it done,” Taylor said. “You can see the traits that got him here.”

Brown’s locker was sequestered with the other rookies. While reporters from local television stations clustered around the nearby stall of first-year quarterback Jake Dolegala, Brown dressed in relative anonymity. He answered questions patiently and showed little irritation over his circumstances. Regardless of what happens with Cincinnati, he said he wasn’t ready to give up on football. “I’m going to keep going until they stop calling,” he said.

Brown was philosophical about his journey to the Bengals.

“I feel like these last couple months, there’s been a lot of adversity, honestly, and nothing really went as planned,” he said. “But I’ve definitely come a long way, and I’m in a NFL locker room right now.”

Brown headed out of the locker room and into the Cincinnati warm night. Outside, fans were still trickling out of the stadium, wearing the orange and black of the Bengals. Many were young, athletic men like Brown who once entertained their own dreams of playing in the NFL. For at least one more night, Brown was on the other side of that line, still a player in a league obsessed with talent, in a city crazy for football.

The following day, Brown was among 21 players waived by the Bengals. He wasn’t signed to the practice squad, and after his release split his time between Phoenix and South Dakota. After working out for seven other NFL teams, he was signed to the Jacksonville Jaguars’ practice squad Oct. 30.

Correction: An earlier version of this article included the wrong college for Eagles center Jason Kelce. He went to Cincinnati, not Villanova.