A therapist’s take on what “Succession” gets painfully right about power and family

For fans of Succession, the Emmy-nominated HBO drama about a powerful media family, Sunday nights can’t come soon enough.

For fans of Succession, the Emmy-nominated HBO drama about a powerful media family, Sunday nights can’t come soon enough.

To hear the opening theme song by composer Nicholas Britell feels like Christmas arriving every time, especially in the show’s current second season, which, the Atlantic notes, reaches “a level of insight and theatricality that rivals anything else on television this year.” A black comedy about a rich, white family in the show’s first season, it has become a layered and emotionally astute study of one in the second.

Psychologist Nancy Burgoyne counts herself among Succession’s admirers, though she can’t help but see the show through a professional filter. Burgoyne is the chief clinical officer at the Family Institute at Northwestern University, which dedicates part of its practice to counseling people in family businesses dealing with tricky issues of succession, among other potentially complicated junctions. She has worked with families struggling with conflicts not unlike that of the show’s fictional family, the Roys.

That crew is headed by Logan Roy, the wealthy aging patriarch whose character loosely resembles Rupert Murdoch. Logan is the tyrannical founder of Waystar-Royco, an ethically questionable media and theme-park conglomerate. He lives largely in denial about his declining health and the urgent need to name a successor. Three of his smart, cunning adult children—Kendall, Roman, and “Shiv” (short for Siobhan)—are left to “play the game”—that is, prove themselves worthy of stepping into the top job and running the business that has defined their lives. Meanwhile, Logan’s oldest son from his first marriage, Connor, is detached and eccentric; he’s presented as essentially safe from his father’s random fits of rage and in any case incapable of becoming anything so real as a chief executive. (The uninitiated can find a fuller description of the roles in my colleague Adam Epstein’s review of the first season.)

Burgoyne, as it happens, also grew up in a family that ran a family business. She was the natural expert for us to consult for a pro take on the Roy family dynamics. What feels real and universal here? What lessons about families or their companies can be pulled from the show?

Fortunately, she was game for this exercise. But, she stressed, she would never speculate about an individual’s psychology the way she does in this interview—“making leaps of the imagination,” she says—if the subjects were real people or public figures. We should all be grateful that the Roys are not.

Note: This interview contains spoilers. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: Have the show’s writers created an accurate depiction of how family dynamics become entangled in business concerns? What works? What is less convincing to you?

A: A lot of people have asked me this, thinking that it was a wild departure from what you would see, but I actually don’t think so. I’ve seen a lot of families do succession planning very well, very thoughtfully, very intentionally, and they would bear no resemblance to this family. But I think what you’re looking at is an amplification of dynamics that a family with this kind of power, and these kinds of players, would really be vulnerable to.

You have an aging CEO struggling to let go of power. His value and meaning are all tied up in that. His mortality, his work—everything. Letting go of this is effectively letting go of who he is and how he knows himself and his worth, and none of us give that up very easily.

His kids have no doubt grown up in an environment where affection and attention were unreliably provided at best, and routinely withdrawn. The expectation for loyalty lived side-by-side with explosiveness and carelessness in communication—painful, abusive, verbal communication. All of that could easily generate the type of sibling dynamics you see, and the type of parent-child dynamics. And you have three marriages. You have all of the ingredients for something quite combustible.

Is the deep reluctance to let go even more intense with founder-CEOs?

Absolutely. For founder-CEOs, in many ways this is their kid, their baby. They feel like they care about it and get it in a way that nobody else possibly could. And they have a very hard time trusting anybody to take it over. It’s not an unusual pattern, actually, for a succession to be initiated and then the founder-CEO struggles quite a bit to to let go and move on. It’s poignant actually.

Logan dangles the possibility of winning the succession game like a carrot.

Yes, especially with the kids, to sort of get them to prove themselves. And in this case, you have to prove yourself to be quite awful in order to impress Logan, and of course there are ramifications for that, too. You really can’t win.

If this family came to you as clients and you had to rank the issues that you would deal with in order of urgency, what would that look like?

I would work with them as a subsystem to start. I wouldn’t see them all together at once. I would be really interested in starting with Logan and his wife [Marcy.] I think she is an influencer behind the scenes. And I’m not 100% sure yet for good or ill. I suspect for ill, because it wouldn’t be that interesting if it was for good. And I would want to get at: How can we influence Logan to reframe this transition in a way that he would feel elevated rather than diminished? The challenge is to find a way for him to feel honored and respected in this transition, and his wife potentially could play a role in that. I don’t pretend with somebody like Logan, who is highly unlikely to submit to a therapy context, that it would be easy or even viable.

The other possibility would be to ask the siblings about the trade-offs that they are making, continuing to involve themselves and vying for power. What are their other options? I assume that they have access to considerable wealth.

You would want to know: Does Logan have some interest in the family having more peace with one another? And if he does, you could leverage that. I think that would be challenging. And so you might have to just talk to the siblings about their relationship with each other and what they want it to look like, and what they could be doing to work more effectively as a group of siblings. Because Logan is going to be gone, and they’re going to be left.

Logan’s rarely seen brother, Ewan Roy, acts as an unseen force, driving Logan’s mania for acquiring PGM, the reputable, Pulitzer prize-winning company owned by the Pierce family and Ewan’s preferred news outlet. What do you see in that sibling pair?

That relationship sort of hints that the pattern of sibling rivalry we see precedes this generation. Often we see that there are trans-generational patterns that play out in the business context or the family context, and this no exception.

I would hypothesize that there were family of origin dynamics between the brothers that long preceded current history, but likely also there was vying for power and credibility as young men, and sort of dividing and conquering various positions in order to distinguish themselves. It’s a keyhole into a longer-standing pattern that probably is part of what drives Logan.

From a psychologist’s perspective, what else we might learn about Logan’s family of origin?

I wouldn’t be surprised if Logan was shamed somehow in his family of origin, in the way that Kendall somehow experiences shame now—because Logan seems to identify with his son, not only because he’s the oldest, but somehow he also identifies with his vulnerabilities, as much as they disgust him. I wouldn’t be surprised if there were some history of abuse or rejection or abandonment, or if he was the adopted one, I really don’t know. But I’d be more surprised if Logan didn’t have some sort of painful family history that would contribute to how driven he is, and how intense he is, and how desperate he really is.

In the latest episode (Ep. 6; “Argestes”), Logan hits Roman in front of the family and other company executives. Was that surprising to you?

Someone asked me if I was surprised by the violence and I wasn’t surprised at all. It’s consistent with his verbal behavior. It’s consistent with tha t appalling scene where we saw with him throwing sausages at people at the business retreat. And Kendall’s reflexive, immediate response to protect his brother seemed familiar. It didn’t seem like there was a moment of shock where anybody stood there like “I can’t believe that just happened.” There was a sense of, “Well, we’re back here.”

Yet, in reality, wouldn’t a family that runs a business together be able to disguise or hide such dysfunction?

The siblings are, across contexts, very unable to contain and manage their distress and their competitiveness with one another. That is great for drama. In real life, people do a much better job of managing what shows up in public settings. For example, at the joint dinner they had with the Pierces [the family that owns PGM], it seemed unlikely that they wouldn’t, with all of their socialization, have been able to manage that better than they did. Through the script, and the choices of what to show, they’re demonstrating something that probably would be just a hair under the surface. Again, this is a troubled family; this isn’t every family.

Shiv, who plays a political spin master and is only now being invited to join the company, lost it at that dinner, blurting out that her father had promised she’d be his successor. That was not supposed to go public.

Shiv is interesting, because in a patriarchal system, she’s been sidelined from access to power and influence, although she’s as smart and savvy as anybody else in the room. And so in some ways she shows up as very sophisticated, and in some way she shows up as very dumb. She first wanted to hide her investment in being part of things by going in another direction, and even going in the direction of liberal politics and doing what what kids in families do, which is divide and conquer. If somebody is a great musician, [the other says] “I’m going to be an athlete.” Kids divide and conquer who can be good at what. But she had to hide an underlying desperation really to be part of it. That scene at the dinner table was a part of her breaking through [and essentially saying], “You’re not going to take this away from me again. No, I’m going to serve myself here. You can’t offer it to me, and then let me not have a seat at the table. I don’t want to be here as an ornament.” But she would have managed it better in real life given all of her training in politics.

Is there a difference usually with the way men and women as adult siblings are treated when it comes to power in a family business?

It depends on the family. I know many families who have been very intentional about including and passing power and authority to the women in the family.

Sometimes what’s tricky—in modern times more than historically, when we just assumed that the males would take over—is you could have somebody in a family who’s an oldest son, for example, who’s a talented musician or athlete or a historian or some other skillset that would be impressive, but not a good fit necessarily to take over a business. Families struggle sometimes when the heir apparent doesn’t have a skill set that fits what’s needed, and they have to be really thoughtful, intentional about dividing money, dividing power so that people don’t feel marginalized. It’s very delicate. I feel for families in these positions.

How are we to understand Kendall and Logan’s relationship right now, in your view?

Kendall is heartbreaking to me. He is probably the most likable of the bunch because of his vulnerability, although they’re all vulnerable in various ways. But for starters, he’s being blackmailed by Logan because they have his secrets about the accident and the death of the man that he was procuring drugs from. But also Kendall carries a lot of shame. He is ashamed of and horrified by that event. He’s ashamed of his substance abuse. He no doubt has been shamed by his father in ways that are obvious on the show and likely long proceeding this period; he is unable to live up to his father’s unreasonable expectations.

Kendall can’t win, even if he’s doing everything right, his father can’t afford for him to be good enough to take over because then it would mean that he’s not needed anymore.

Is that a common conflict in family businesses, that potential successors don’t know if a boss and parent is on their side?

There are family dynamics where that is the case. But I’m very familiar personally and professionally with parents who would like nothing more than to have one or more of their children succeed in taking over the business—or wouldn’t have a problem with them deciding they didn’t want to have anything to do with it. That’s a little harder for founder-CEOs, but I’ve seen it work both ways.

Is it common for a half-sibling like Connor to be so physically and emotionally removed from everyone else and the family business?

In a step-family situation—people like to call them blended families, but we tend to shy away from that because it’s more like a fruit salad than a smoothie—people do maintain their individual identities. And that’s healthy, if it’s understood and respected that they are different sub-systems and they’re also a family.

The relationship with Connor makes sense. He’s more on the outside relative to the others, and he had a different experience and a different mom.

I would be remiss if I didn’t ask about Roman’s sexual hangup, his need to be humiliated, even if it doesn’t directly affect the family business and knowing you’re not a sex therapist.

I’m a clinical psychologist. I have 30 years of experience. I’ve seen lots and lots of families and couples, but I would be reluctant to comment with great authority about Roman’s sexuality—except to say that someone’s sexuality is influenced by many things, and it could be influenced by abuse, but I wouldn’t want to assume that anybody who had those sexual preferences had that history. There are many paths to the same outcome. In this case it seems like Roman has been humiliated on a regular basis so that is part of his sexual expression.

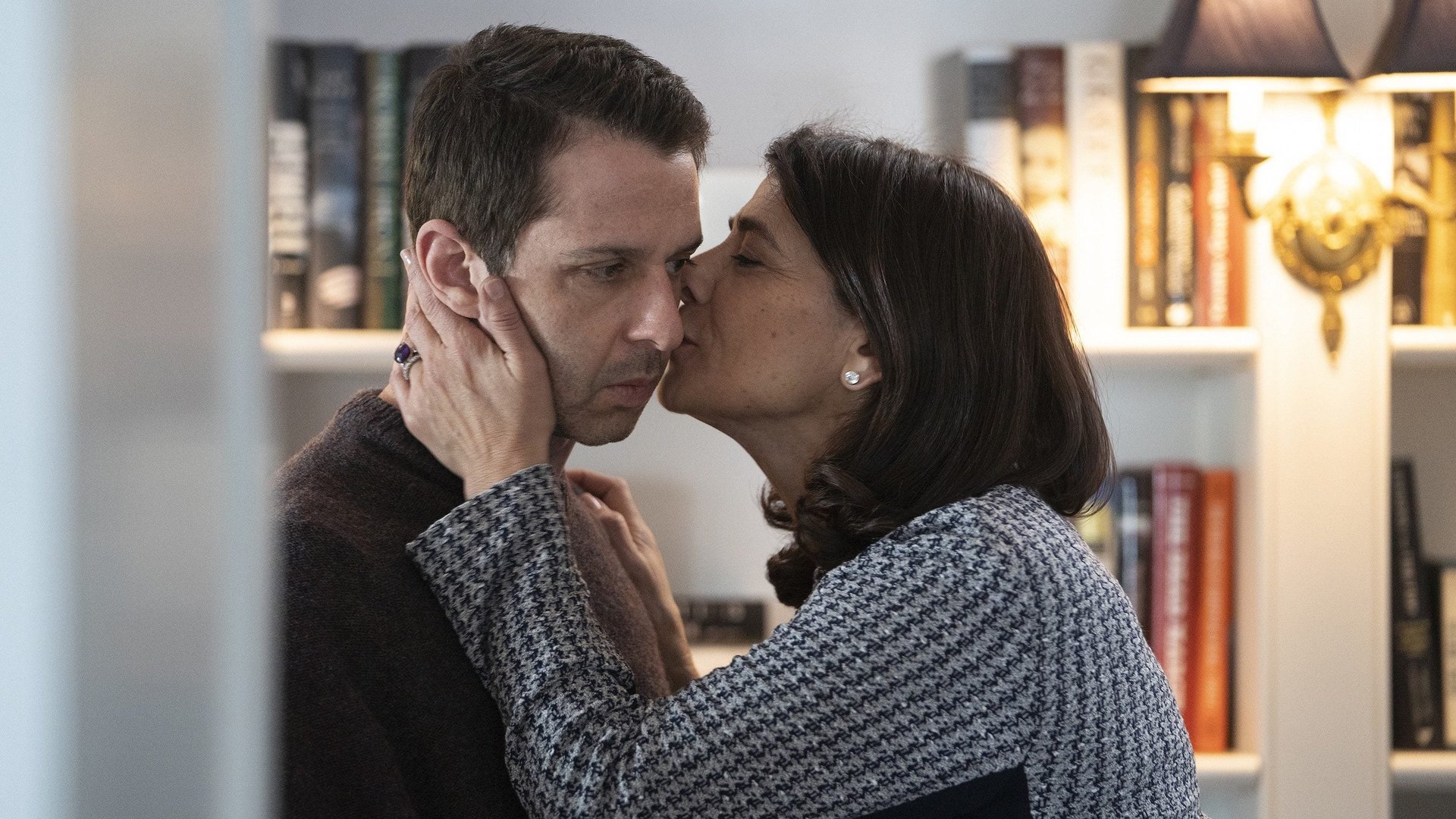

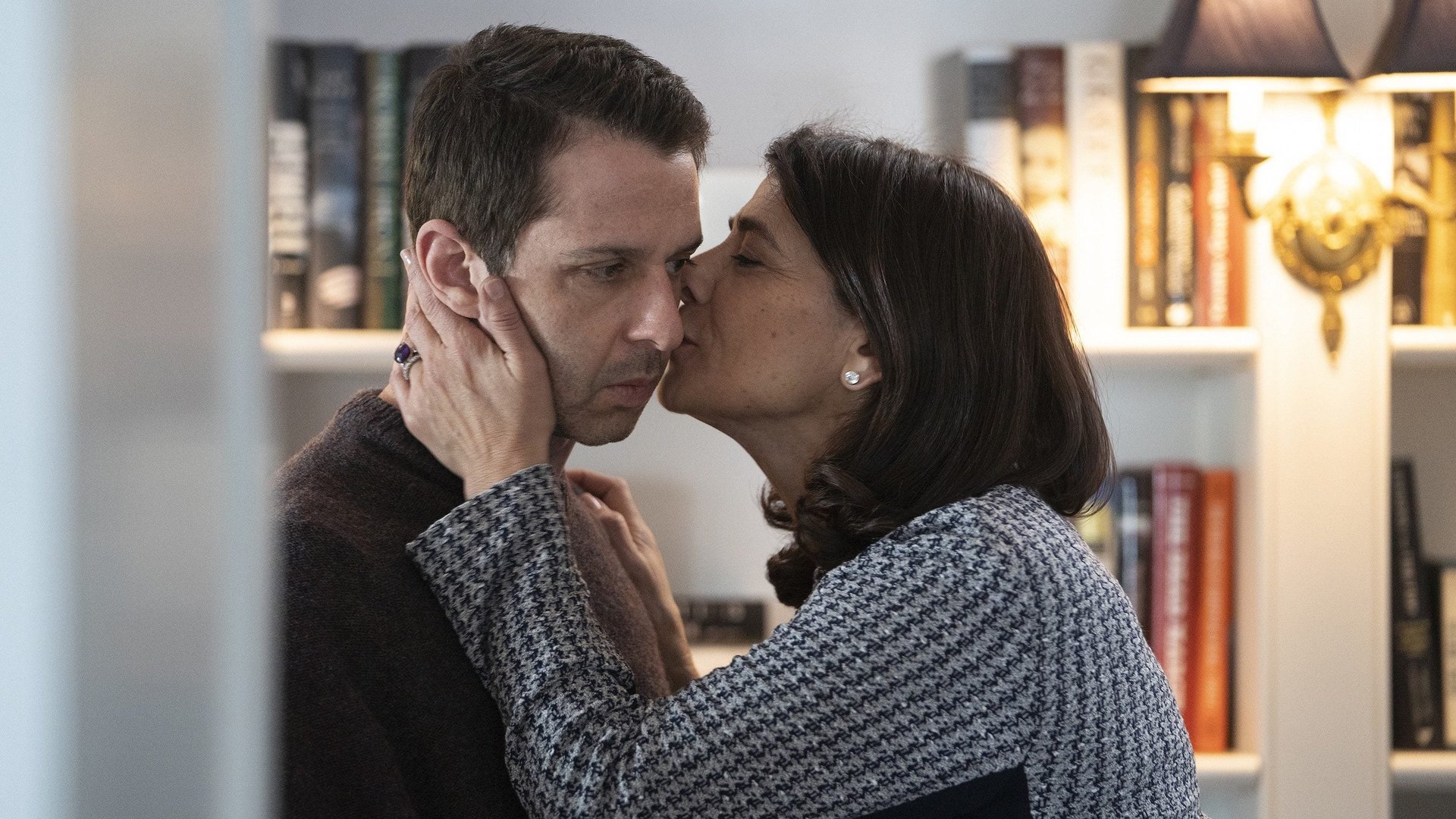

He has also found a mother figure in Gerri, as their sexual relationship continues. Does that happen with family businesses, where outsiders take on familiar roles?

Sure. In any number of contexts, a person can step into the role of a mentor-slash-surrogate-parent, whether that’s a school situation with a teacher, or a work situation with a boss, or a situation with a more senior co-worker. There are lots of people with pockets of need.

There’s nothing that’s inherently problematic with people finding other people in their environment who meet that need, especially if someone is doing that intentionally. I always say I hope my kids have many mothers because one mother can’t cover it all. What can be problematic is the intensity of the need, when boundaries are violated in the pursuit of that need. People in power can sometimes exploit that need for their own good, so a professor or therapist that sleeps with their student or client, for example.

What do in-laws like Shiv’s husband, Tom, experience working within a family-run business?

I think it’s hard to ever be anything but in-but-out. Different families have a stronger or looser boundaries around the nuclear family system and it can be more or less difficult for in-laws to penetrate that. Some families are very inclusive and welcoming, while others not so much. With Tom, because he is male and Shiv’s husband, it seems like giving him an in was a way to indirectly throw Shiv a bone.

Sounds like you would also ask Tom about the trade-offs he’s making, too?

That’s such a basic and important question in therapy generally. In life, generally, it’s like we’re always getting something and losing something and nobody wants to lose something, but you end up losing the most when you don’t choose your losses.