Why CEO turnover in 2019 is so damn high

Ah, autumn: When the air turns crisp, leaves take on shades of scarlet and ochre, and CEOs of troubled companies quit their jobs.

Ah, autumn: When the air turns crisp, leaves take on shades of scarlet and ochre, and CEOs of troubled companies quit their jobs.

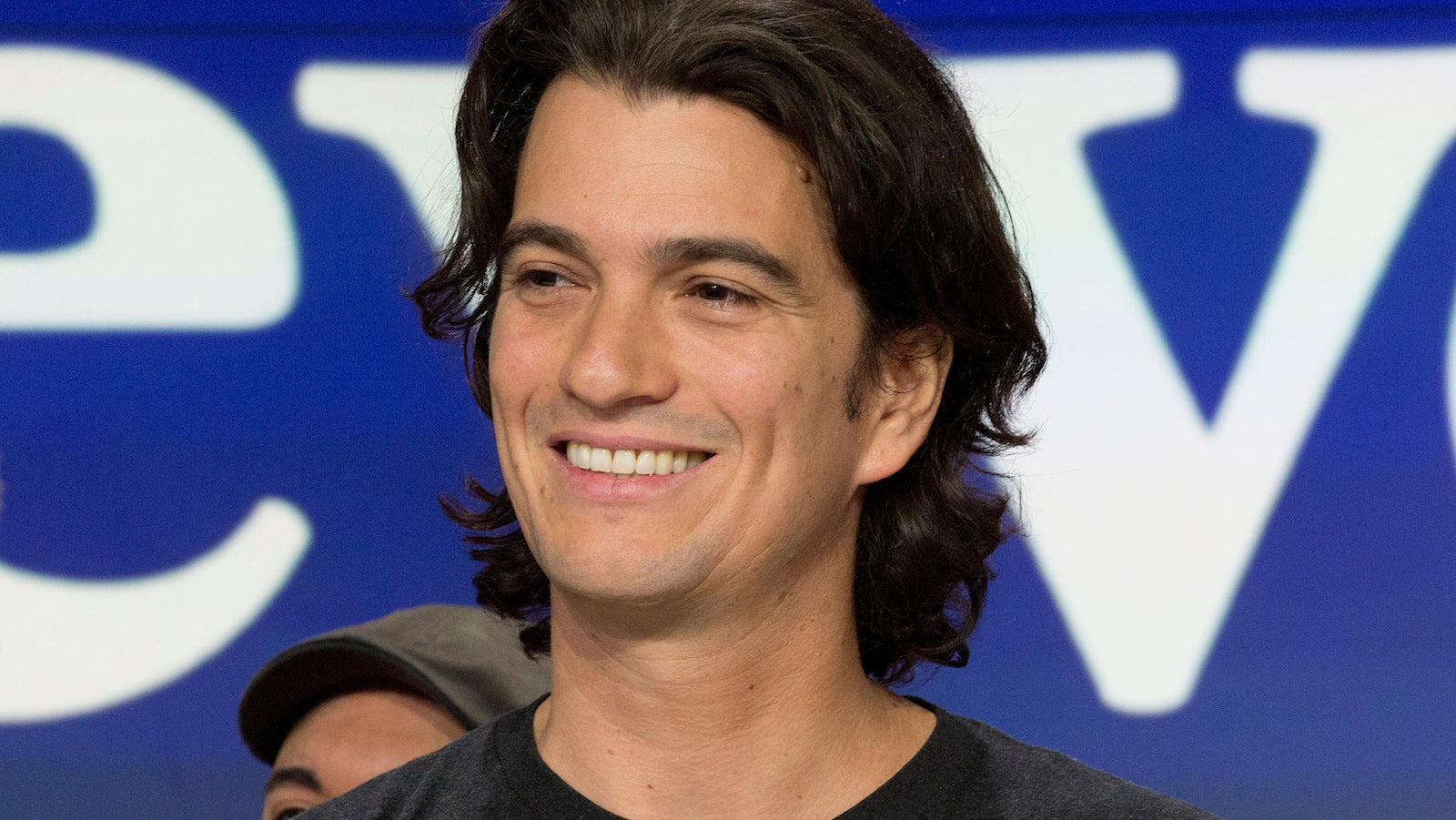

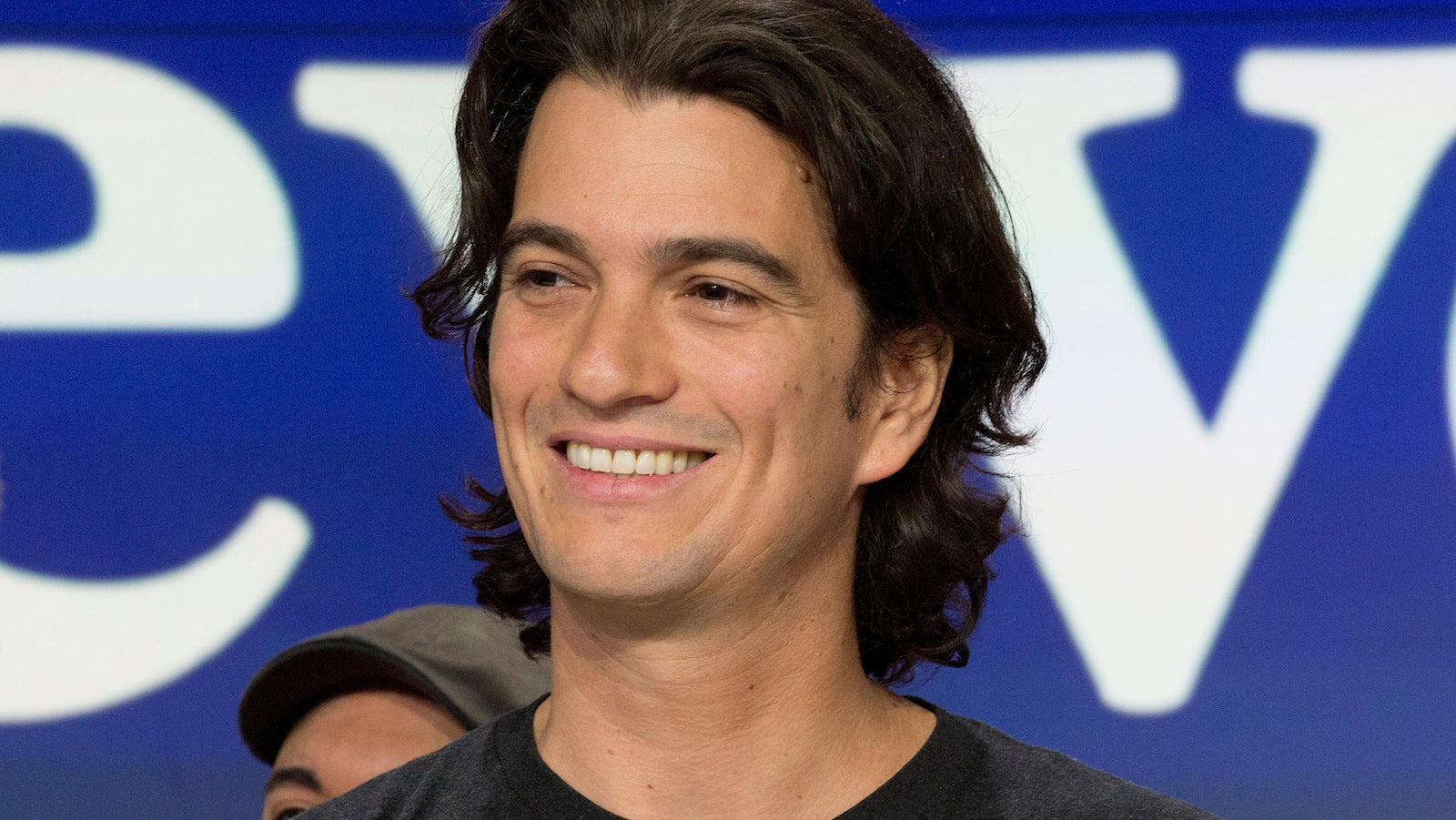

This September saw a string of high-profile executive departures, including WeWork’s Adam Neumann and Juul’s Kevin Burns, prompting speculation that investors’ patience with the leaders of big, buzzy, controversial startups was wearing thin. That may well be true, but a new report suggests that Neumann and Burns are just one part of a much bigger trend.

A total of 1,160 CEOs in the US have left their jobs in the first nine months of 2019, according to data from recruitment firm Challenger, Gray, & Christmas. That’s up 13% from the same period in 2018, and the highest turnover at this point in the year since the company first began tracking CEO departures, in 2002. (The data considers companies in business for at least two years and with 10 employees or more.)

In September alone, 151 chief executives stepped down, well above the average of 110 exits during that month in previous years.

So why is it that so many captains are jumping ship—or, in some cases, walking the plank—in 2019? Here are a few hypotheses.

Fears of a recession have investors spooked

“With growing uncertainty surrounding global business and market strength, the fact that so many companies are choosing this moment to find new leadership is no coincidence,” Andrew Challenger, vice president of Challenger, Gray & Christmas, said in an August release. Indeed, CEOs themselves cited an economic downturn as their number-one worry in a Conference Board survey published at the start of this year. The reasons they gave for their concern included trade wars and global political instability.

Recent economic data doesn’t suggest that a US recession is imminent. But markets are notoriously sensitive to the prospect of a downturn, and this can affect stock prices. So investor anxiety about a recession, whether or not one is actually happening, can be enough to convince the board that a shakeup is in order.

Investors are fed up with founder-gurus

This hypothesis is particularly relevant for Silicon Valley. Tech has experienced the second-highest level of CEO turnover out of any industry this year. Its total of 154 departures was bested only by the 246 in the government and nonprofit sector, according to Challenger, Gray & Christmas.

As Quartz’s Alison Griswold wrote when Neumann was pushed out from WeWork following his company’s disastrous attempt at an IPO, the audacity, charisma, and boldness that made Neumann so successful also proved to be his downfall. Drawing a connection between Neumann and Uber’s disgraced co-founder and former chief Travis Kalanick, Griswold notes that the venture capitalists who bought into the “cult of the founder” allowed the companies to flourish even while their leaders racked up losses and engaged in deeply problematic behavior.

But WeWork’s botched effort at going public, along with the disappointing IPO performances of companies like Uber and Lyft, have shown that the market is far more skeptical about the value that self-mythologizing founder-CEOs claim to have created. “Investors are saying, ‘We’re not going to tolerate this nonsense anymore’,” Matt Stoller, a fellow at the Open Markets Institute, told The New York Times after Neumann’s ouster.

The graying of the CEO

Another straightforward explanation for the heightened turnover is that some CEOs really are leaving to spend more time with their families. The average age of a male CEO in the US is now 58, while the average age of a female CEO is 56, according to a 2019 report (pdf, p. 36) from Crist|Kolder Associates that gathered data from Fortune 500 and S&P 500 companies.

That means there are a lot of leaders at, or nearing, retirement age. “Companies that have done well are implementing succession plans that have long been in place,” Challenger notes in the release. But a new class of younger, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed CEOs doesn’t necessarily mean that the rate of departures will slow in coming years. A 2019 study from PricewaterhouseCoopers found that successors to long-serving CEOs “are likely to have shorter tenures, worse performance and [are] more often forced out of office than the CEOs they replaced.”