The secret to creative success is to stop caring about recognition

Getting three Michelin stars is a dream come true for many ambitious chefs. Losing one, however, is a nightmare.

Getting three Michelin stars is a dream come true for many ambitious chefs. Losing one, however, is a nightmare.

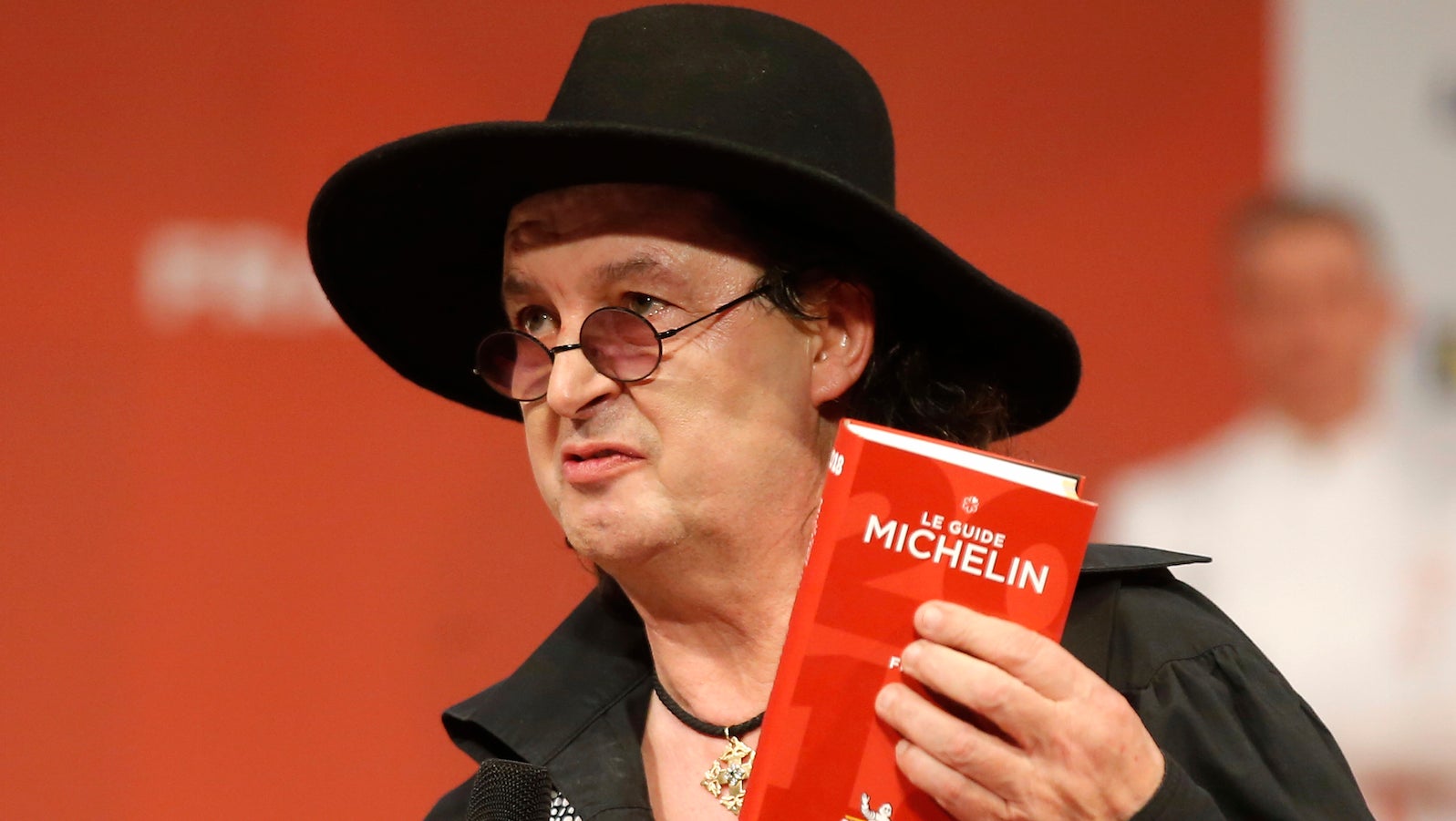

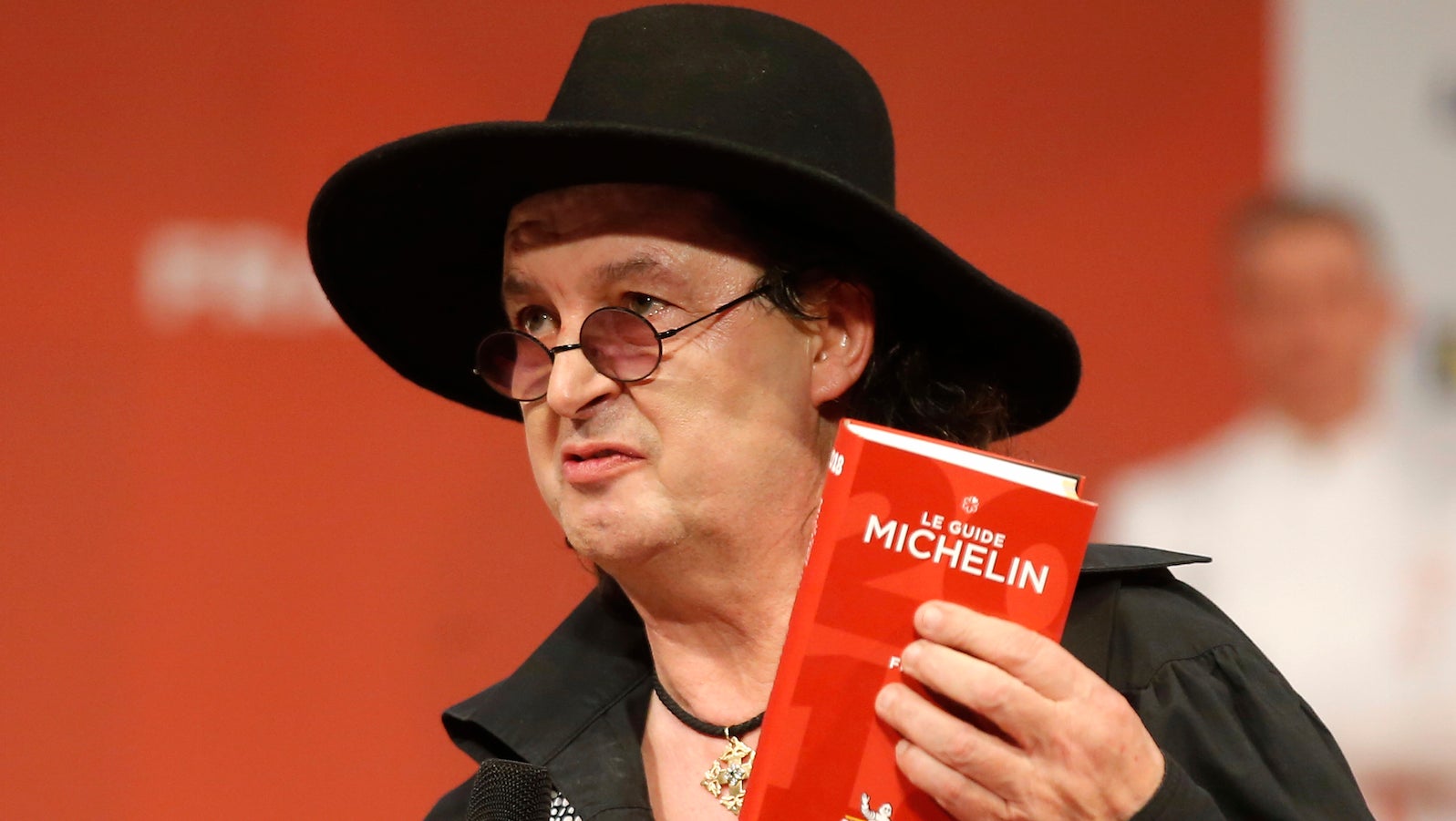

Such was the fate that befell French chef Marc Veyrat, after the Michelin Guide last January downgraded his restaurant, La Maison des Bois, from three stars to two, prompting him to bring a lawsuit against the world-renowned restaurant guide. “I feel as if my parents died a second time,” Veyrat told French publication Le Point.

But the harm was mainly just psychological. Business remained brisk at La Maison des Bois—revenue was up 10% from the previous year, the chef himself admitted. And so a French court ruled against Veyrat, finding he had failed to provide “proof showing the existence of any damage” to his restaurant as a result of Michelin’s actions.

But Veryat is less concerned with the consequences of Michelin’s decision than with the process behind it. He sued in order to gain access to the Michelin reviewer’s notes and receipts from the visit to his restaurant, known for its innovative approach to molecular gastronomy and featuring local ingredients and vegetables foraged from the hills of France’s Haute-Savoie. According to The New York Times, his lawyer compared Veryat’s mission to that of a student who refuses to “accept being graded without knowing the grading criteria or the scoring.”

In this quest for answers, Veryat was always doomed to fail. Had he won the lawsuit and dug into the reviewer’s notes, it’s unlikely he would have found proof that he deserved to keep the Michelin star he’d lost, or that he’d ever deserved three stars in the first place. That’s because awards and ratings are subjective and arbitrary, whether the recognition involves a Michelin star, an Employee of the Month certificate, or the Nobel prize.

The problem with judging

One reason awards and rankings are inherently flawed pertains to the people in charge of them. In Veryat’s public comments, he has repeatedly suggested that Michelin authorities are incompetent and unqualified to judge cuisine. “The Michelin, they’re basically amateurs. They couldn’t cook a decent dish,” he said in an interview with Lyon Capitale.

In a letter published by Le Point, Veryat claimed that when he asked Michelin for an explanation for the drop in his restaurant’s ranking, the only reason he was given was actually a case of mistaken identity. The reviewer had noted that La Maison’s soufflé contained cheddar, when in fact it was a Reblochon and Beaufort emulsion. “It’s a shame for the region,” he declared.

Michelin denies any such cheese confusion, and says it stands by its rating. And while it’s impossible to assess the individual qualifications of its inspectors, given that they’re anonymous, most of them are chefs with at least 10 years of experience in the restaurant or hospitality industries. They’re hardly food novices.

They are, however, human beings, who inevitably bring with them their own preferences and biases and gaps in knowledge.

Indeed, we’re all disposed to like certain things more than others, for reasons that may have little to do with quality. The Michelin guide has long been accused of elevating French food above other cuisines, for example, just as Academy Award voters are known to swoon over period dramas and actresses wearing facial prosthetics. These preferences aren’t wrong per se—it’s not as if things would be any more fair if Michelin inspectors favored Thai food instead, or if the Oscars reliably rewarded superhero films. But they suggest, as does scientific research, that there’s no way to be truly objective in our assessments of other people’s work. As Marcus Buckingham and Ashley Goodall point out in The Feedback Fallacy, a 2019 cover story for Harvard Business Review:

Our evaluations are deeply colored by our own understanding of what we’re rating others on, our own sense of what good looks like for a particular competency, our harshness or leniency as raters, and our own inherent and unconscious biases. This phenomenon is called the idiosyncratic rater effect, and it’s large (more than half of your rating of someone else reflects your characteristics, not hers) and resilient (no training can lessen it).”

But it’s no use trying to protest an award committee’s decision by pointing out its blind spots. Human nature dictates that, when we’re criticized over our decisions, we’re all the more likely to double down on them. Louis Menand described one such noteworthy example in The New Yorker, writing in 2005 that “[w]hen the first Nobel Prize in Literature went to Sully Prudhomme, in 1901, the choice was regarded as a scandal, since Leo Tolstoy happened to be alive. The Swedish Academy was so unnerved by the public criticism it received that its members made a point of passing over Tolstoy for the rest of his life—just to show, apparently, that they knew what they were doing the first time around.” Today, Tolstoy remains one of the world’s most renowned authors; the French poet and essayist Prudhomme, much less so.

Yet the Nobel judges weren’t necessarily mistaken. Rather, in picking Prudhomme instead of Tolstoy, they underscored the baffling mechanisms by which one person’s worth is elevated over that of another; and in continuing to deny him the honor, they perhaps made these mechanisms, which so many awards and rankings try to hide, temporarily visible.

The lesson of the Nobel story isn’t that Tolstoy deserved the award and Prudhomme didn’t; it’s that the award was nothing for any one person to genuinely deserve over another in the first place.

Distinguishing between degrees of excellence

Rankings typically involve picking one “best” person or company or project from a pool of excellent choices, attempting to signal, whether via Michelin stars, a top 10 song list, or stack-ranking performance reviews, exactly how good something is in comparison to other good stuff.

This is a fool’s errand. It can be fairly straightforward to tell the difference between an overcooked steak and a tender, well-seasoned sirloin, or to distinguish between the good employee who does their work competently and efficiently, and the bad one who leaves a trail of missed deadlines and sloppy mistakes in their wake. But who’s to say that one innovative architectural design is more important or groundbreaking than another, or if the better employee is the person who excels at leadership and problem-solving or the one who’s always proposing creative new projects?

Well, judging by the number of awards given out and ranking compiled on a daily basis, we’re to say! But we’re bad at it. It would be far more accurate to say that awards and rankings communicate our favorite things, rather than the best. The New York Times recently admitted as much when its music critics looked back at their top 10 albums from each year of the past decade. In contrast to the idea that “a critic spends months absorbing as much available music as possible, then puts it all in order of greatness,” the truth is that a top 10 list involves “some combination of that process and how a critic felt on one particular day. The lists are up for revision and reflection. They might look different, even regrettable, with the benefit of hindsight.”

Companies, too, are increasingly aware of the injustices and inconsistencies that arise when ranking employees against one another. Describing Uber’s stack-ranking review process back in 2017, Quartz reporter Alison Griswold noted that employees she interviewed complained of “managers awarding higher scores to friends or favorites, to the detriment of other team members,” and that “people who received glowing feedback from coworkers could still find themselves being handed a one or two by a manager, sometimes with little or no explanation of why.” Uber overhauled the review process later that year, getting rid of employee ratings in an effort to evaluate workers more fairly, and adding concrete individual goals around performance to make the assessments less subjective.

I had the chance to experience the difficulty of discerning degrees of excellence firsthand last year, when I was a judge in a writing contest. My main qualifications were that I write and that someone else had recommended me to be a judge. I was assigned to review a pool of submissions. Then I got on the phone with two other judges, and together we picked the winners.

There was no way to establish which story was objectively better than another; they were all remarkable pieces of work. Yet choices had to be made. So we recognized one for its innovative presentation, and another because it had a particularly unusual story to tell. Another set of judges might have produced an entirely different set of top picks—just as another Michelin inspector might have paid a visit to La Maison des Bois and decided it deserved to retain its three stars.

Back in 1964, the critic Susan Sontag warned against the dangers of reductive attempts to evaluate and assess art. The chief argument in her landmark essay “Against Interpretation” (pdf) is that interpretation often seeks to prevent us from paying attention to what we feel. “What is important now is to recover our senses,” she declared. “We must learn to see more, to hear more, to feel more. Our task is not to find the maximum amount of content in a work of art, much less to squeeze more content out of the work than is already there. Our task is to cut back content so that we can see the thing at all.”

Honors and awards are a kind of interpretation; they tell us which professionals to hire and how much to pay them, or which films and books and restaurants are most worth our money and time. But this is often a misdirection. When we understand just how fallible they are, we have a better shot at peering past the veil of prestige and perceiving the world on our own terms, rather than worrying about the difference between two stars and three, or separating the Prudhommes from the Tolstoys.

Living with equanimity in the awards economy

The simplest solution to the problem of awards and rankings would be for society to do away with them altogether. But as long as people and their products and projects require some kind of validation in a capitalist economy, we’re unlikely to ditch our rating systems.

Some people, made miserable by the pressure and constant striving for awards and recognition, may seek to eliminate themselves from the process. Indeed, Veryat, like fellow French chef Sébastien Bras, among others, has asked to give back his Michelin stars—a desire that, while symbolically important, is not technically possible, as the stars are awarded to restaurants rather than individuals.

Perhaps the better approach is simply to treat even big honors lightly, with the knowledge that attempting to position ourselves to win a high ranking or prize will only make our work worse.

As argued in a 2017 article about the “fetishisation” of academic excellence, published in the social sciences journal Palgrave Communications, “the hyper-competition that arises from the performance of ‘excellence’ is completely at odds with the qualities of good research,” encouraging corner-cutting, fraud, and conventionality rather than collaboration and experimentation. David G. Evans makes a similar argument in The Chronicle of Higher Education, in a piece about how teaching prizes impact teachers, noting, “A professor whose goal is to win a teaching award can be tempted to focus on using varied and creative teaching styles, rather than on student learning and its assessment.”

It’s no wonder that attempting to attain—or retain—a particular distinction can lead to a dip in both our mental health and our quality of work. In attaching our self-worth to the outcome of what is bound to be an arbitrary decision, we’re prone to driving ourselves a little crazy.

It’s far easier to be happy, creative, and productive when we accept that all awards are essentially meaningless (and that they nonetheless will continue to be distributed all around us for the rest of our lives). With this mindset, if an award or honor happens to come our way, we’re pleased but unlikely to develop an overinflated ego, with the knowledge that it just as easily could have gone to someone else. And if we get passed over, we may be sad—but not too much, because we know that if conditions had been even slightly different, it might have been us.