Virtual meetings are about to turn the art of management into a scalable science

We see computers everywhere except in the productivity statistics, economist Robert Solow once said. Indeed, while the internet age has given us mobile phones, cloud computing, Skype, and social media, economic productivity in the world’s richest countries has been dismal. From 2014 to 2018, the US government’s official labor productivity measure grew by just 1% per year on average.

We see computers everywhere except in the productivity statistics, economist Robert Solow once said. Indeed, while the internet age has given us mobile phones, cloud computing, Skype, and social media, economic productivity in the world’s richest countries has been dismal. From 2014 to 2018, the US government’s official labor productivity measure grew by just 1% per year on average.

But this productivity paradox might soon change, in large part because of Covid-19.

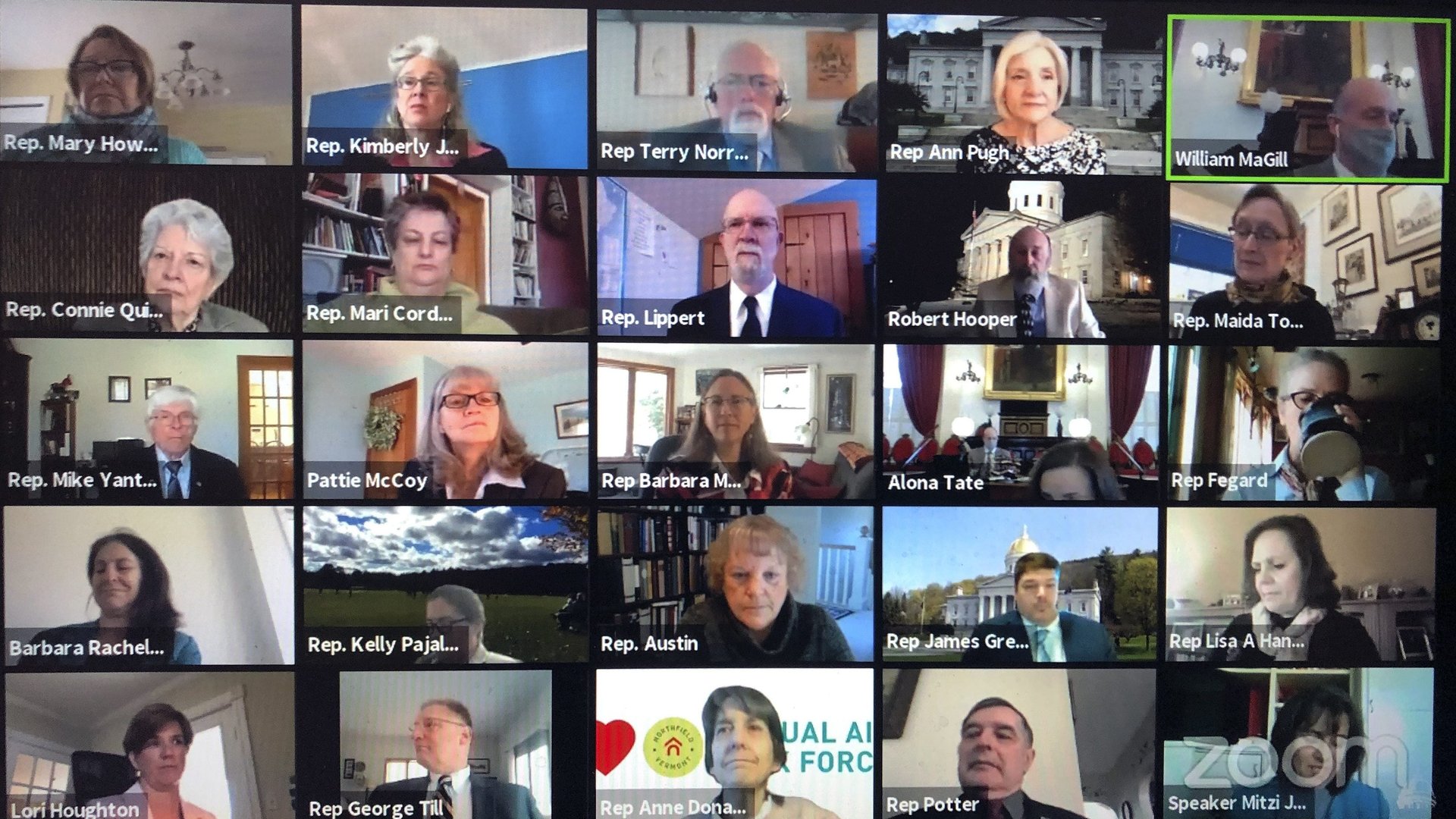

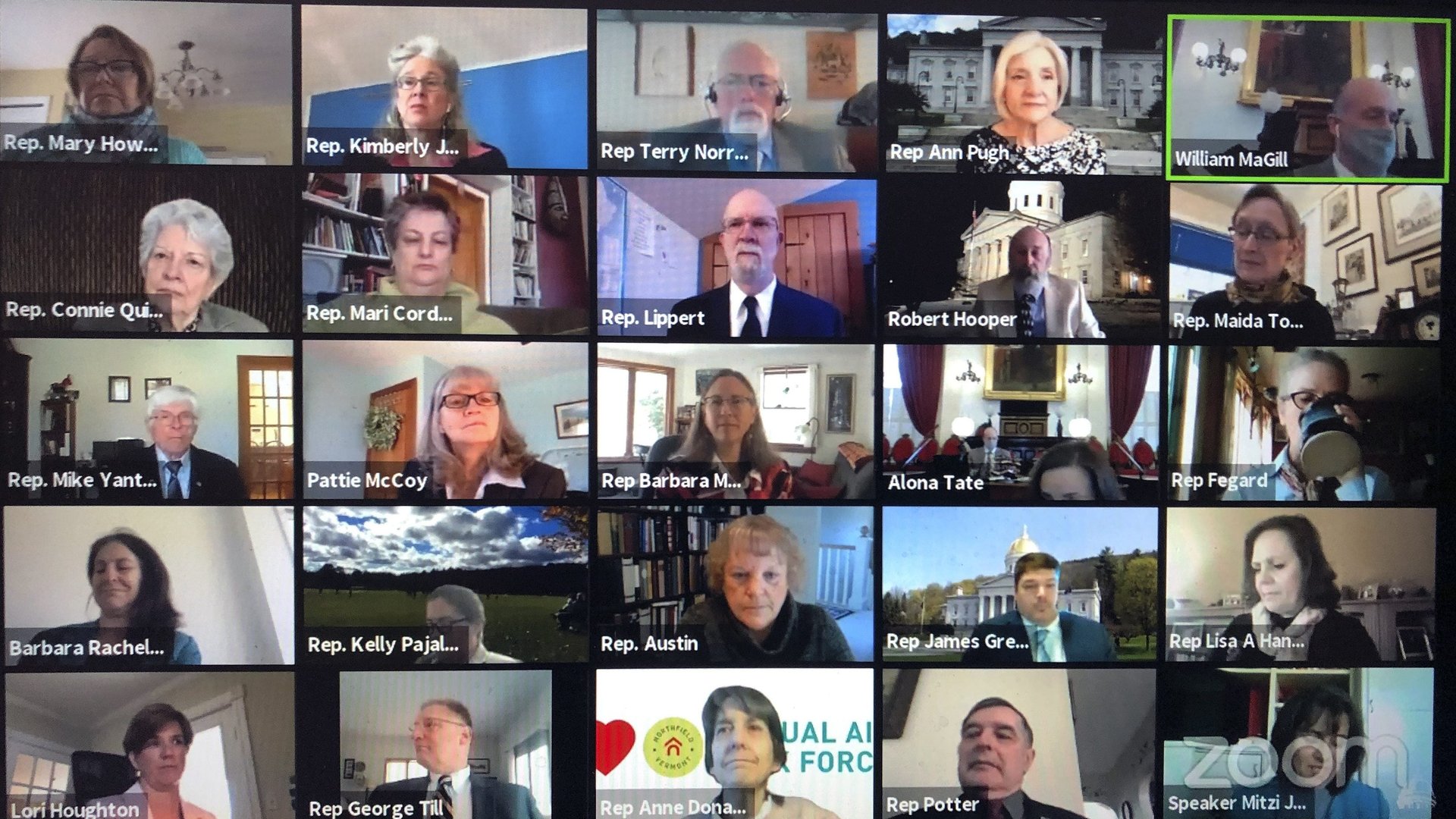

As travel bans and social distancing have forced big companies to shift to working from home en masse, video conferences and messaging platforms are substituting for almost all face-to-face communication to keep operations running smoothly.

We are, unwittingly, producing a staggering digital library on how managerial decisions are made.

Far from emailing minutes of a meeting that summarize only the conclusions, the digital footprint captures the entire deliberation process, from emotions to facts, from tirade to discussion, from opposition to consensus. Embracing remote work tools like Zoom, Slack, and Microsoft Teams thus allows companies to capture an elusive yet vital ingredient to skills development: tacit knowledge.

Acquiring tacit knowledge is normally a slow process

Tacit knowledge refers to information that is hard to articulate and transfer, including through the writing of manuals, equations, and software code. In contrast, Google’s search engine, and its method of ranking web pages on the internet, can be explicitly described in the form of a mathematical formula. The ranking formula looks like this: PR(A) = (1-d) + d (PR(T1)/C(T1) + … + PR(Tn)/C(Tn)). That’s explicit knowledge. Now try to write down a formula for closing a tough sales negotiation. Impossible. Except for a few tips for staying assertive, how can anyone articulate all the subtle moves a masterful salesperson engages in when closing a tough deal?

The process of learning tacit knowledge is time consuming, and it doesn’t scale. Highly tacit knowledge that can only be transferred from a master to an apprentice takes time to learn; it can take years of practice to perfect a technique or a skill.

Hence, the more tacit knowledge is involved in an organization, the more important face-to-face meetings are among its managers. Apple, for instance, when compared to Google and Facebook, is especially reliant on face-to-face meetings. Apple engineers like to touch and view the physical parts of a product in person. They conduct stress and drop tests of their designs in the laboratory. Other times, they huddle around a 3D printer or a milling machine.

The more face-to-face meetings there are, the fewer opportunities there are to develop an algorithm to automate those human decisions. And the fewer the algorithms that can be deployed, the lower the productivity gain achievable by computers. In other words, when we fail to capture the tacit knowledge that is so central to management decision making, algorithms can’t help improve productivity. We see computers everywhere except in the productivity statistics.

But it doesn’t have to be this way

Consider Bridgewater Associates, the world’s largest hedge fund, with around $160 billion in assets. What founder Ray Dalio did some 30 years ago seems prescient today. Well before Zoom or WebEx, Dalio endeavored to videotape every managerial meeting and hired a small team to edit the tapes, focusing on the most important moments. Dalio and his team turned the lessons gleaned from the tapes into case studies for employee training; materials such as these helped Dalio to cultivate a unified culture of “radical transparency.”

More recently, Bridgewater has developed apps including the Dot Collector, which is installed on every employee’s company iPad. Employees bring their iPads to every meeting and use the app to give and receive real-time feedback in the form of publicly viewable “dots,” or data points. A proprietary algorithm then processes the dots and calculates attributes such as an employee’s “believability” and aptitude for certain roles within the company. By recording and quantifying data from meetings, employees can continuously assess and adjust their performance—complementing more formal, isolated training sessions—and assist managers with making decisions about staffing and team structure.

What Bridgewater demonstrates is that productivity gains are possible with recorded observations. Digital interaction is the first foundation, as it renders itself recorded and, thus, codified. With Zoom, DingTalk, Slack, and WeChat Work being all the rage, we’re one mere step away from turning video content into analyses.

Companies need not be as sophisticated as Bridgewater to distill tacit knowledge from human interactions and reap some benefits. Zoom, for instance, partners with AISense, a startup that focuses on automating transcriptions, converting voice conversations between multiple parties into text. Its mobile app (Otter.ai) imports discussions directly from Zoom. It doesn’t take much of a logical leap to see how computer-assisted textual analysis of recorded video can be done at scale.

Audio analyses from phone calls can also form useful banks of tacit knowledge. Cogito, a start-up founded by MIT professor Alex Pentland, zeroes in on word frequency, vocal tone, and pitch, among other factors, in customer service conversations. It helps staff members understand when their tone is too aggressive, or if they are interrupting. It reminds people when they are supposed to say something, or to raise their voices. An experiment conducted by MetLife found that such AI-driven “nudges” improved “first call resolution” by 3.5% and customer satisfaction by 13%.

Instant messaging conducted on Slack, Google’s G Suite, and Microsoft Teams can also serve as a trove of insights. Analytics company Humanyze, for one, deploys algorithms that use behavioral science to uncover patterns in written communications. Crunching the anonymized data reveals content flow dynamics and how teams share ideas, identifying which groups are cohesive, who is not engaged, and where bottlenecks exist.

Small tweaks made in response to the findings can generate big consequences when applied with precision. When a pharmaceutical company noticed a performance gap between sales teams, Humanyze discovered that employee engagement drove productivity, and that tenured employees were less engaged. Knowing the issue was not a lack of technical training, the company simply connected tenured employees with younger people to participate in team-building activities. The underperforming teams caught up with the more productive ones after a few months.

We have the tools now

As the Covid-19 pandemic spurs the adoption of digital communication and collaboration tools across industries, smart companies are emancipating themselves from the tyranny of tacit knowledge. But unlike the clumsy efforts led by SAP, Siebel, and Oracle a decade ago, it looks relatively easy this time. Plenty of digital tools are now either free or cheap and easily accessible, and there’s plenty of reason to expect that companies will keep using them even once the crises recedes.

What started as an innocent move to virtual meetings out of necessity has spearheaded an inexorable reform of how corporate decisions are made. And this is how a new wave of productivity gain is finally unleashed.

Howard Yu is the LEGO professor of management and innovation at the International Institute for Management Development (IMD) Business School in Switzerland. Mark J. Greeven is a professor of innovation and strategy at IMD, and Jialu Shan is a research fellow at the Global Center for Digital Business Transformation, an IMD-Cisco initiative.