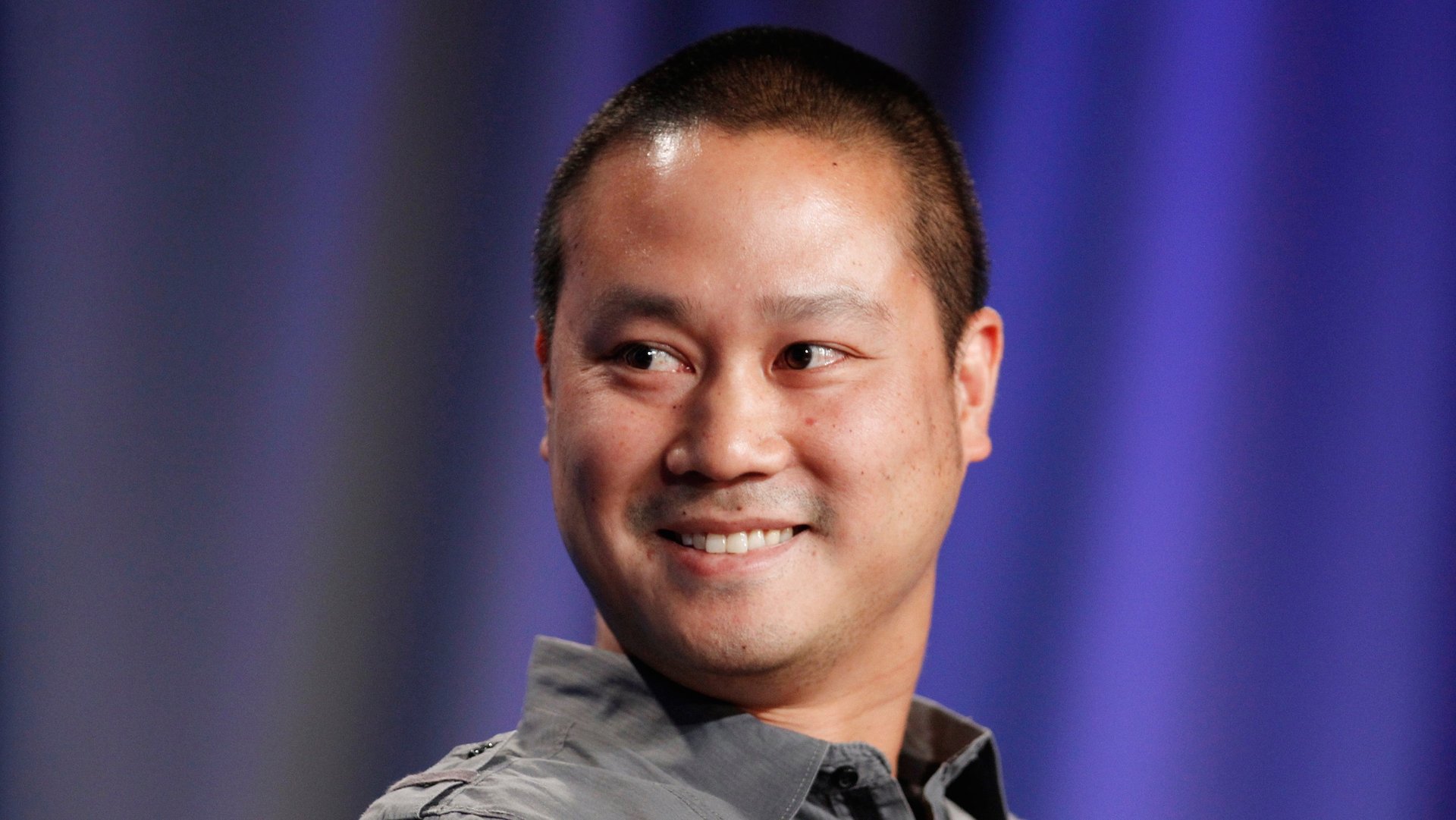

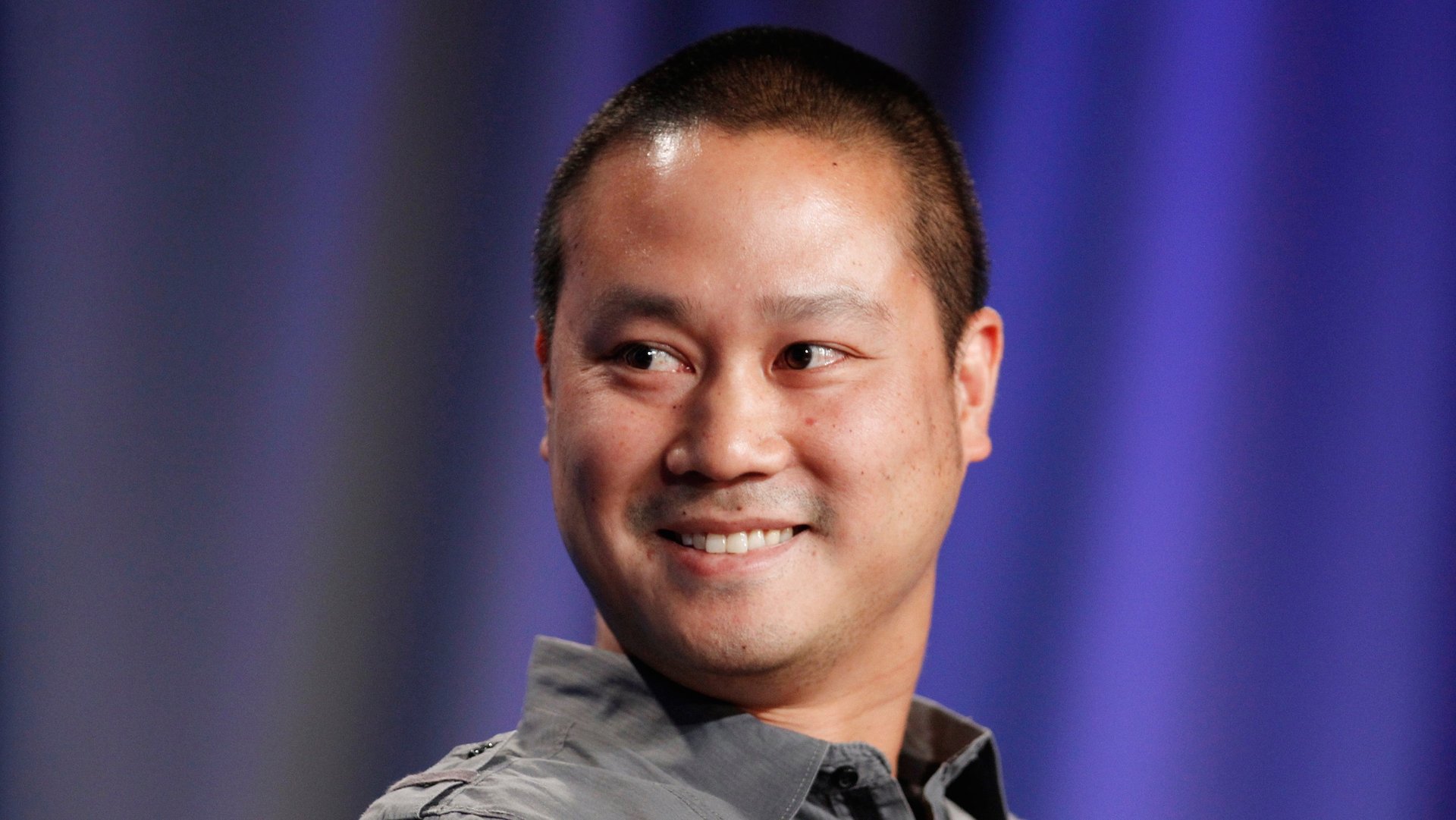

The lessons of Tony Hsieh’s quest for employee happiness

Tony Hsieh wanted to make people happy: customers, employees, everyone. It was a goal that was as prescient as it was ambitious.

Tony Hsieh wanted to make people happy: customers, employees, everyone. It was a goal that was as prescient as it was ambitious.

As CEO of the online shoe retailer Zappos for 21 years, Hsieh, who died Nov. 26 at age 46 from injuries sustained in a house fire, was an early pioneer in espousing employee happiness as a top business priority. His quest to create an environment where workers felt enthusiastic about their jobs and, by extension, their lives, is an indelible part of his legacy—one that reveals both the promise and the pitfalls of happiness as a corporate goal.

The Zappos culture of fun

Today the idea that corporations should care about workers’ well-being (or at least claim they do) is so commonplace that it’s a part of the official statement on the purpose of companies issued by the Business Roundtable in 2019. CEOs like Zoom’s Eric Yuan and Menlo Innovation’s Richard Sheridan have gone even further, following in Hsieh’s footsteps to commit themselves publicly to the idea that when employees are happy, productivity and profits tend to follow.

But when Hsieh was steering Zappos through the 2000s and early 2010s, the idea that an ambitious, growing company would care so much about worker happiness tended to raise eyebrows. In a 2010 interview with WNYC’s Marketplace, interviewer Kai Ryssdal questioned the sustainability of Zappos’ culture during a visit to the company’s Las Vegas headquarters, telling Hsieh that there was a “sizeable group that’s standing around chit-chatting. There’s a party down the hall that’s been going on for an hour. How does all this affect actually, day in and day out, selling shoes?”

Hsieh didn’t deny that his company needed to sell shoes and make money. He just thought that socializing with co-workers—inside and outside the office—was essential to achieving those goals. When managers bonded with their teams, he told Ryssdal, productivity went up: There were “higher levels of trust, communication is better, people are willing to do favors for each other because they are doing favors for friends, not just co-workers.”

To Hsieh’s way of thinking, having fun at work wasn’t a liability; it was an asset. In his 2010 book, Delivering Happiness, he boasts about running the kind of office where departments set up makeshift bowling alleys and throw impromptu Oktoberfest parades.

This festive approach to corporate life gained increasing popularity with the second big tech boom. First startups and then more traditional employers turned to facilitating social opportunities as a way to keep workers engaged—and, according to critics, tethered to the office, putting in 16-hour days without any expectation of overtime. All those in-office happy hours and pinball tournaments, Lab Rats author Dan Lyons told Wired this year, are just “a way to distract employees and keep them from noticing that their pockets are being picked.”

The office as center of social life

That said, Delivering Happiness suggests that Hsieh had a very real, personal stake in envisioning the workplace as a locus for close relationships. He writes of realizing in his 20s how important a sense of belonging was to his personal happiness, and vowing “to make sure I never lost sight of the value of a tribe where people truly felt connected and cared about the well-being of one another.”

He found that feeling while attending his first rave, where “the entire room felt like one massive, united tribe,” and went about trying to recreate it at work, first at the San Francisco penthouse suite that served as Zappos’ early party spot and (at one point) rent-free employee housing complex, and later, with the company’s move to Las Vegas. In the book’s opening scene, as he discusses Zappos’ sale to Amazon during an all-hands meeting, he is touched by “the unified energy and emotion of everyone in the room,” and transported back to the transcendent feeling that he experienced at that first rave.

Happiness research supports Hsieh’s thoughts on the importance of relationships: Social connections and community are essential to our emotional well-being. Where things get complicated is his idea of the workplace as the social focal point of his employees’ lives. “Probably the biggest benefit of moving to Vegas was that nobody had any friends outside of Zappos, so we were all sort of forced to hang out with each other outside the office,” he recalls in Delivering Happiness. He later told the New York Times that he favored the idea of “work-life integration” over “work-life balance.”

It seems clear that Hsieh genuinely enjoyed this approach in his own life. But such sentiments may raise red flags for readers concerned about the ways the 21st-century workplace has eroded barriers between employees’ work and personal lives. When socializing with co-workers becomes an expectation, rather than an option, it penalizes working parents and others with caretaking responsibilities—and may deepen, rather than bridge, racial and cultural divides.

The problems inherent in placing so much value on work relationships were also evident in the Downtown Project, Hsieh’s wildly ambitious bid to turn downtown Las Vegas into a startup city. The entrepreneurs involved with Hsieh’s project had left their friends and family behind to go to Las Vegas. That meant that they spent a lot of time together. But reporting in 2014 on a three suicides among entrepreneurs involved with the project, writer Nellie Bowles found that the expectation of constant after-hours socializing took a toll on many founders there. Since their social lives were inextricable from their work lives, with a lot of time spent courting venture capitalists, they weren’t able to be emotionally honest and vulnerable about the struggles and pressures they faced as they tried to get their companies off the ground.

“We call it ‘face’ in China — everything’s great, we’re doing great,” one founder told Bowles. “But at the end of the day, you need a community, a safety net. You don’t want to air out these issues to your investors, but if there are only investors around, then what do you do?”

The cost of positivity

Maybe seeking constant happiness, whether on behalf of ourselves or others, is simply too much pressure for everyone involved. There is, after all, only so much that a CEO can do to create the conditions in which workers thrive. Fair pay and generous benefits go a long way; so does helping people to identify a sense of purpose in their work.

Beyond that, individual temperaments and circumstances will vary. Some employees may be searching for exactly the kind of fun-loving, close-knit community that Hsieh wanted to provide; they’d be happier working at Zappos than spending their days at, say, a buttoned-up bank. Others may prefer to keep their work and personal lives separate, and so the very efforts meant to boost morale could well backfire and make them more anxious or frustrated.

But making space for people to air such feelings doesn’t seem to have been Hsieh’s style. However well-intentioned his efforts to spread happiness were, the relentless pursuit of positivity often means that there’s not much space for dissent or discussion of the darker aspects of human existence.

He famously paid new Zappos hires $2,000 payout if they quit shortly after joining the company, in order to weed out people who weren’t a good fit from the get-go and preserve company culture. When employees struggled to adjust to Zappos’ new holacracy management structure, Hsieh offered several months’ severance to anyone who wasn’t fully on board, hoping to be left with only the true believers. (Nearly 20% of Zappos workers took the buyout, and the company ultimately moved away from a strict interpretation of holacracy.)

All this was apparently done in the service of maintaining an upbeat atmosphere. And to be fair, evidence suggests Zappos employees are mostly happy at their jobs. Current and former employees give the experience of working there 4.1 out of 5 stars on the job-review site Glassdoor, and it’s frequently landed on lists of the best companies to work for. But there’s also reason to think Hsieh would have done better to listen to the holacracy haters rather than getting rid of them—to make room for the people Adam Grant calls “disagreeable givers,” the insightful malcontents who push organizations to do better, and who might have saved Zappos years of implementing a system that ultimately wasn’t serving the company.

As a general rule, when we try to eliminate conflict or repress negativity, happiness only becomes more elusive. Research shows, for example, that there are real psychological costs to acting happy when we aren’t. Conversely, people who accept their darkest emotions rather than denying them tend to experience less depression and anxiety and react with more resilience to adversity. As journalist Aimee Groth, who got to know Hsieh personally while writing a book on the Downtown Project, notes in her tribute to his flawed but expansive vision, “failure and suffering is a more instructive teacher than unconscious success.”

As new details about the circumstances surrounding Hsieh’s death continue to surface, the business world is grappling with the question of how to remember his life. Perhaps among the most important lessons to take away is that employers can care about their employees—as Hsieh did—without expecting, or asking, them to be happy.