You lived through the fastest economic recovery in three decades

The number of prime-age Americans at work has risen above its pre-pandemic peak

The latest data on the US labor market marks a particularly notable moment: Prime-age labor force participation—the share of 25-to-54-year-old Americans at work—has risen above the peak set in 2020, immediately before the pandemic.

Suggested Reading

The result shows just how remarkable the recovery from the pandemic recession has been. After the 2008 financial crisis, prime-age labor force participation didn’t recover for more than twelve years; it took just just over three this time around. Following the 2001 recession, the share of prime-age workers in the labor force never recovered! But in March 2023, the employment rate for people in their prime age working years rose to 80.7%, the highest it’s been since 2001—and the unemployment rate for Black Americans fell to an all-time low.

Related Content

The US government’s response to covid kept the wheels on

The rapid recovery in prime-age employment can be attributed to a number of choices made by policymakers in the US and around the world. The combination of massive investment in the development of new vaccines and generous subsidies to employers and citizens allowed the US to pass through the worst of the pandemic without leaving its economy in shambles.

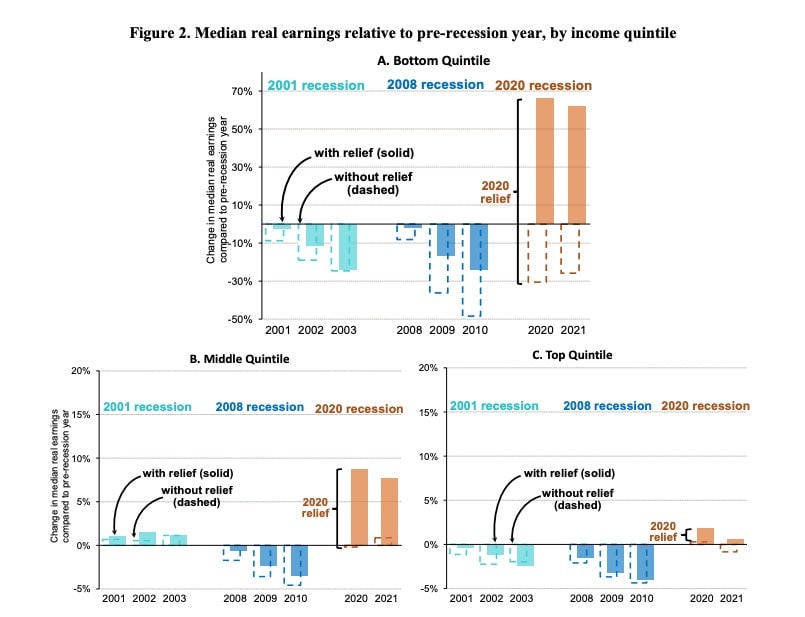

That massive fiscal push included expanded unemployment payments, loans to businesses that kept workers on the books, checks sent to individual taxpayers, and Federal Reserve lending to back-stop the financial system. The US was among the most generous nations in the world when it came to handing public cash over to families. Federal Reserve researchers published a paper comparing the policy responses to the last three US recessions. This set of charts, showing how the lowest, middle, and highest earners fared, is enlightening:

It gibes with other research that shows income inequality has plateaued in recent years thanks to a tightening job market.

Inflation is falling and a soft landing remains in sight

Part of the cost of all that generosity has been a year of elevated inflation, which peaked in June 2022 when the Consumer Price Index rose 8.9% over the previous year; it has fallen steadily to just under 6% since then. But it is difficult to disentangle fiscal policy’s affects on prices from the real economic changes caused by the pandemic, whether in the shift from services to goods, or in supply chain hiccups around the globe.

The Fed’s tightening of interest rates has impacted several sectors, notably housing. But thus far it has done more to shake up the financial sector, through Silicon Valley Bank’s failure to adapt to changing interest rates, than it has to disrupt the labor market.

Indeed, recent data suggests the dream of a soft landing—a period of slowing inflation without a recession—is still alive. Wage increases are slowing to levels that match more closely with the Fed’s inflation target, thanks in part to the rise in labor force participation discussed above; since November, we’ve seen the largest increase in the labor force in 50 years, Employ America’s Preston Mui observes.

That’s not to say the US is out of economic danger. Regional banks are still shaky, if stronger than a few weeks ago, and their lending is likely to tighten; some surveys of manufacturing are showing slowdowns; and it’s not clear how much tightening the Fed has yet to do. But the rapid recovery of US employment should remind us of the counterfactual in which millions of Americans remain jobless and dependent on public benefits years after a crisis.