Update:

Tinder’s privacy breach lasted much longer than the company claimed

Tinder, the popular mobile dating app that matches people based on how they rate each other’s photographs, briefly exposed the physical location of its users to other people on the service.

The location information wasn’t visible in the app. But the data files sent to each user’s phone, which could be accessed through a simple hack, contained sensitive information about people recommended by Tinder, including their most recent location while using the app. It also included their Facebook ID, which could be used to identify someone by first and last name.

Tinder hasn’t disclosed the privacy slip to its users, but it confirmed the issue after Quartz asked about it, saying the data was only exposed for a few hours this weekend. ”We had a very, very, very brief security flaw that we patched up very quickly,” Tinder CEO Sean Rad said. “We were not exposing any information that can harm any of our users or put our users in jeopardy.”

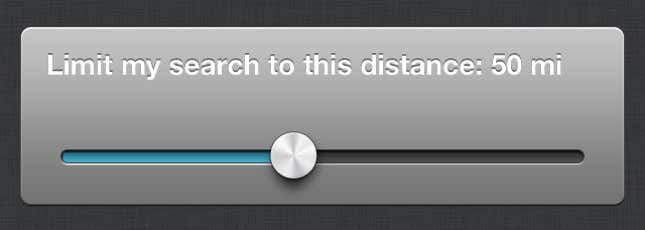

Users are asked to share their location with Tinder so the app can recommend people within a certain distance. To make that feature work, Tinder has to record the last known location of each user. Rad noted that, to preserve battery life, Tinder doesn’t store as precise a location as it could. And the location is only as recent as the last time someone used the app.

But specific location data isn’t supposed to be revealed to other users, and most people would consider that a violation of their privacy. The Facebook ID might also be considered sensitive; Tinder only uses first names in order to conceal people’s identities. The issues are heightened by the fact that people use Tinder to hook up, which raises the specter of stalking.

Tinder has an API, or application programming interface, that facilitates communication between Tinder’s apps and its servers. That API isn’t documented anywhere, but Chintan Parikh, a web developer, was able to piece it together by examining the data traveling back-and-forth between Tinder’s app and its servers.

“I was surprised at the data it returns,” Parikh wrote in an email to Quartz.

It would be impossible to determine if anyone else accessed user location data over Tinder’s API. Rad said one other developer contacted the company about the issue around the same time as Parikh. Asked why Tinder hasn’t disclosed the issue to users, Rad said, “It was a minor flaw that didn’t impact any of our users, so we decided it wasn’t worth bringing to their attention.”

Tinder launched in September 2012, and has seen strong growth for a dating and hook-up app. People like the ease of rating people based on photos—swipe left to dismiss someone; swipe right to indicate interest—as well as the quality of Tinder’s recommendations, which are based on each user’s location and Facebook network. Quartz profiled the startup last month.

A Tinder app for Android phones was released last week, and Rad attributed the security issue to code written for the app’s release. He couldn’t provide a precise timeline of when the issue began and when it was fixed, but said it was a matter of hours.

“It happens as you’re developing products,” Rad said. “I don’t even know if it merits a story.” (Update: After this story was published, Rad said he was misquoted: “I definitely did not say that ‘this happens’ as we develop products,” he wrote in an email. On Twitter, he also denied saying “I don’t even know if it merits a story,” but then deleted the tweet. Quartz stands by the quotes.)

Mobile apps have been criticized for misusing location data. The Wall Street Journal found lots of popular apps transmitting that information to advertising companies. In its privacy policy, Tinder reserves the right to do that, too.