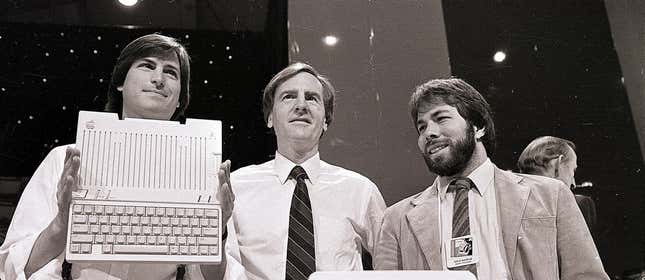

Hartmut Esslinger was already a big name in the field of industrial design in 1982, when his firm, Frog Design, bid on a secret project to help Apple become the company that would transform computers from “business machines” into consumer goods.

After he submitted the Red Book—a binder full of design inspirations ranging from Walt Disney cartoons to the pioneering Sony Trinitron televisions designed by Frog—Esslinger won the Apple contract, and an intimate, decade-long relationship with Steve Jobs began.

Now retired from Frog Design, Esslinger wants to set the record straight about the history of design at Apple. In a new memoir, Keep it Simple, to be released October 9 at the Frankfurt Book Fair, he claims that almost everyone has missed the true lessons of Apple’s early days.

Throughout the book, Esslinger slams the bad guys—mostly John Sculley, the Apple CEO who pushed Jobs out, but also other project leads and executives at Apple—and describes his own work with the kind of superlatives that Jobs was famous for applying to Apple’s products. Ultimately, Keep it Simple is either a monumental act of egotism or the epitome of the inspired bluntness that Jobs was famous for—most likely it’s both.

Quartz got an exclusive advanced look at Esslinger’s book, and what follows are some of the more interesting excerpts:

“I make no secret of my disgust for all those books written by outsiders who, if they mention design at all, describe it as Steve’s hobby or some kind of whimsical ‘add-on’ to his main product focus. Even Walter Isaacson’s much-touted Jobs biography falls into this disappointing category.”

One of Esslinger’s central assertions is that Steve Jobs was no design genius when Apple began, and yet design became central to Apple’s subsequent success. Getting the company to the point that it could produce world-class consumer goods required something akin to a corporate civil war, pitting Jobs and small groups of engineers and designers against the rest of the company.

In this formulation, Jobs is something like Luke Skywalker, fighting the forces of evil, both without (IBM and its drab PCs) and within (the power struggle that ultimately forced Jobs out of Apple in 1985.) That essentially casts Esslinger as Obi Wan Kenobi.

When Silicon Valley didn’t know what design was

![The IBM PC was “cobbled together of sheet metal, metal casting and cheap-looking (but costly) plastic parts disguised under expensive paint jobs [and] could have been manufactured in any plumber’s shop,” writes Esslinger.](https://i.kinja-img.com/image/upload/c_fit,q_60,w_645/df96138ed5c259f96de48687b4f400f8.jpg)

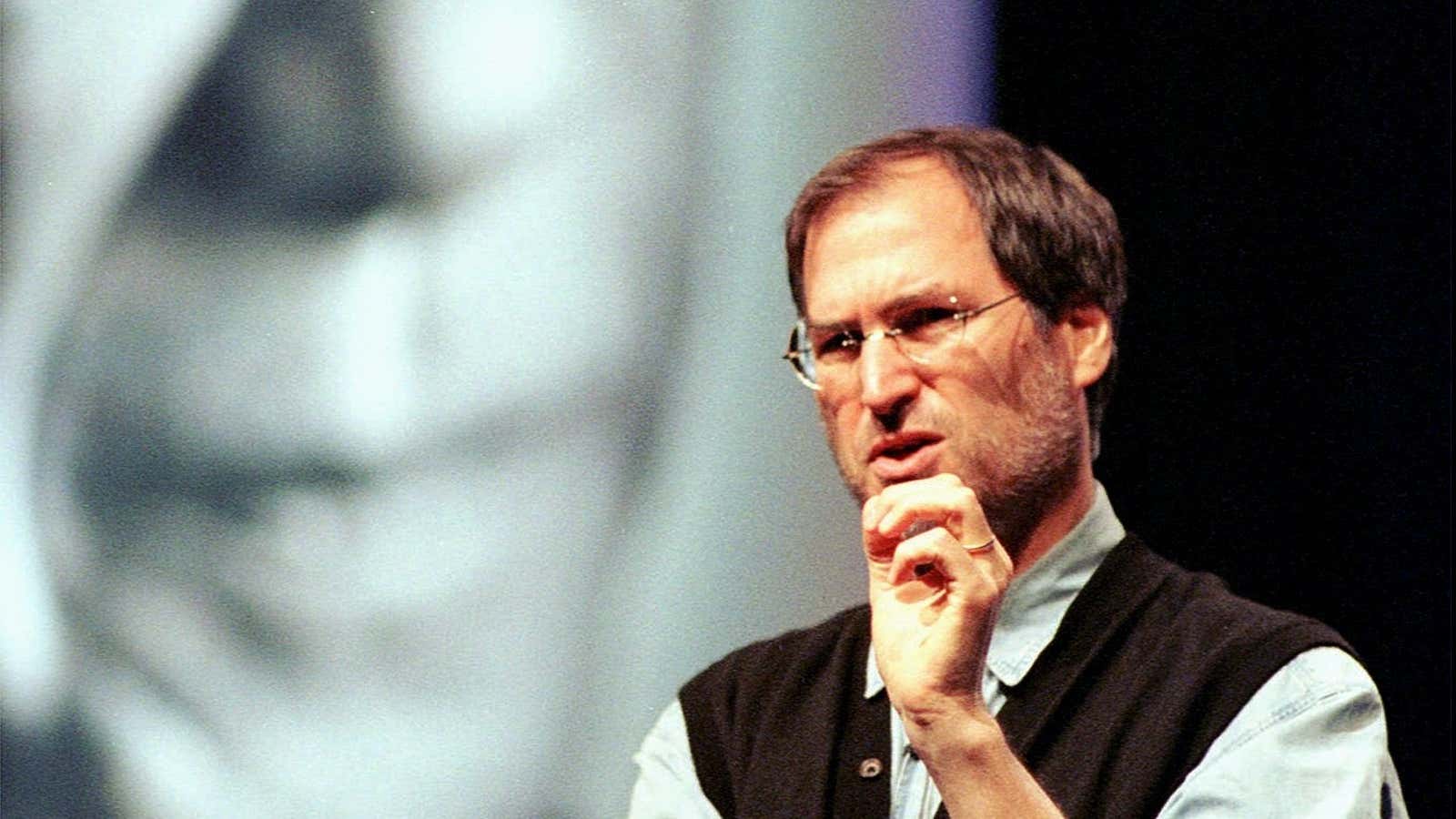

“When we started to work together […] Steve intuitively sensed what design could do for Apple, but both he and his team remained stuck in the provincial perception of design that permeated the engineering-driven culture of Silicon Valley. […] Steve wanted World-Class Design. He was still trying to define what that meant, but he knew that Apple didn’t have it—in fact, aside of Bill Moggridge who had come from London, there wasn’t any true design talent in all of Silicon Valley.”

A friendship with Jobs is born

The day Esslinger met Jobs, he showed up in a t-shirt and jeans. He’d been informed that Jobs was the sort who might throw him out of his office immediately. Already nervous, his anxiety only increased when the first person to come out of Steve’s office was wearing a three-piece suit.

As it turned out, on that day Steve was wearing clothes even rattier than Esslinger’s. When Esslinger asked about the man in the suit, Jobs laughed and said, “That was Governor Jerry Brown—he’s looking for a job.”

Almost immediately, Esslinger told Jobs that designers were often hamstrung by their low position in corporate hierarchies, including at Apple, which resulted in “structurally determined mediocrity.” This irritated Jobs, but Esslinger continued:

“I explained that to make design a core element of Apple’s corporate strategy, it would have to be seen as a leadership issue; world-class design can’t work its way up from the bottom, watered down by the motivations and egos of every layer of management it passes through.”

Their conversation also touched on areas they had in common.

“Steve didn’t really know much about design, but he liked German cars. Leveraging that connection, I explained that design like that has to be a complete package, that it must express the product’s very soul; without the excellent driving experience and the history of stellar performance, a Porsche would be just another nice car—but it wouldn’t be a Porsche.”

An outsider becomes chief of design at Apple

Before long, Jobs had signed an exclusive, $1,000,000 a year contract with Frog, guaranteeing that the firm would only design computers for Apple. (Years later, this contract would become problematic when Esslinger followed Jobs to NeXT computer; Tim Berners-Lee later invented the World Wide Web using the iconic NeXTcube, which Frog also designed.) Esslinger insisted on being in charge of all product design at Apple. All of the company’s internal designers would answer to him; and Esslinger himself would be answerable only to Jobs.

It was a direct implementation of what Esslinger insisted upon, in his first meeting with Jobs: Designers couldn’t simply be at the table: They had to be in charge. This leads to Esslinger’s central lessons for all companies aspiring to be like Apple: Beautiful design requires designers in charge.

“…bottom-up design never succeeds, because even good efforts by departments within such systems remain insulated within the layers of the company’s organizational structure and everything really new, courageous and potentially game-changing is destroyed by its passage through ‘the gates of rejection.'”

Judging by how often he repeats it, this is the most important message of Esslinger’s book. This is also the lesson that Apple’s imitators seem to miss most often—that good design arises as much from the internal structure of a company as from whether or not it’s a priority. Technology firms are founded and often run by engineers—and the natural tendency of engineers is to ruin good design.

Apple’s future is its past—is that a problem?

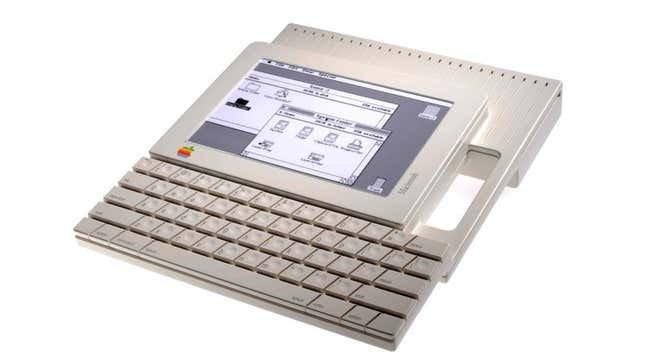

One of the shocking things that comes from reading an account of the early days of design at Apple is how the groundwork for almost all of the company’s subsequent successes—slim notebook computers, the iPad and the iPhone—was laid in the early 1980s. Phones, tablet computers, Powerbooks were all realized by Frog Design in models, at a time when the technology to realize them simply didn’t exist. Then Jobs was kicked out of Apple, learned some hard lessons at NeXT, started a little company called Pixar and returned to Apple just as technology was catching up with his vision.

If Apple’s greatest successes are all rooted in a time when Frog and Jobs were in their creative prime, is Apple in danger of running out of ideas, and turning into a company that is devoted not to innovation but endless refinement of its greatest hits?

One possible interpretation of Keep it Simple suggests that Apple’s recent promotion of Jony Ive—the Esslinger of Apple’s later years—is exactly what the company needed to remain a design-centric, innovative company.

To the extent that it reflects the attitude that Jobs and his lieutenants brought to their work, Keep it Simple could become a classic of both business and design school reading lists. If you’re like Steve Jobs or Hartmut Esslinger, good design is about getting your ideas past the “morons”—which, Esslinger recalls, was “Steve’s favorite word.”