China’s import data surprised many today when it revealed that its traders bought 397,459 tonnes (438,124 tons) of refined copper in January, just shy of the record 406,937 tonnes imported in December 2011, and up 63.5% on January 2012.

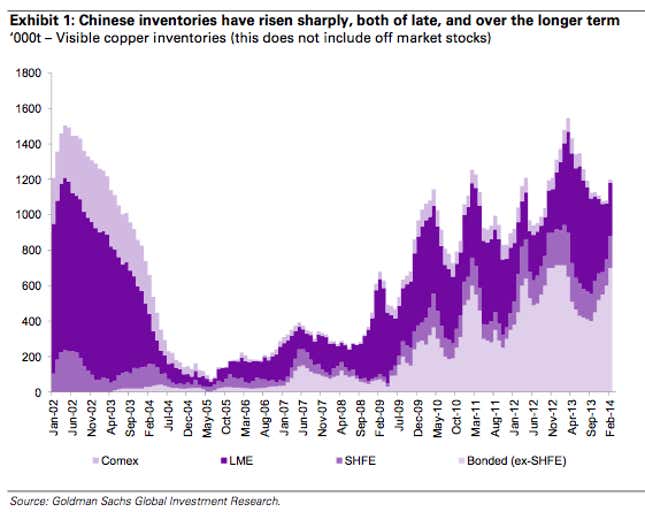

Weird, given that industrial activity appears to be contracting. And really weird, given that copper stockpiles in Shanghai hit a nine-month high. In fact, as FT Alphaville reports quoting Citi, if you count other port cities such as Guangzhou, Ningbo and Rizhao, there could be as much as 1 million tonnes of refined copper sitting in China’s bonded warehouses right now.

But Chinese copper demand is often about financing, not fundamentals. Banks commonly accept copper contracts and inventories as a basis for extending credit. As we reported a year ago, copper-backed credit often surges when money gets tight. And the possibility that Chinese credit conditions could cause a reversal in this trade—as may now be starting to happen with steel—is scary, considering that China currently consumes around 45% of the world’s copper.

Mind you, it’s always hard to read economic data in January and February, due to distortions from the week-long Chinese New Year holiday. However, while some traders attributed the uptick to bringing forward February copper deliveries, other traders told Reuters that the acute scarcity of cash in December was to blame. That, they said, caused investors to buy more spot copper as a way to obtain financing for other investments. The big bump may come from the fact that those contracts arrived in January.

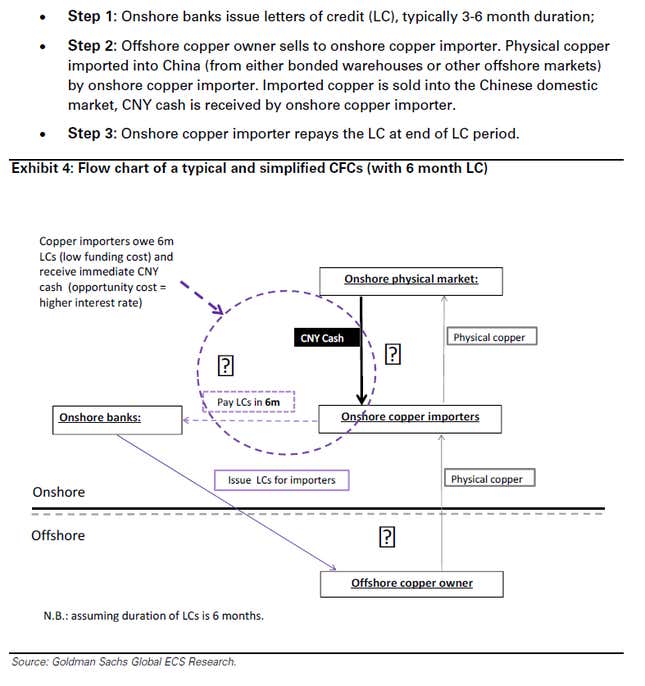

How does all that work? In the simplest terms, investors use offshore-bought copper, kept in tax- and duty-free bonded warehouses, as a collateral for a 180-day letter of credit, a short-term loan, from a bank. They then invest these funds in high-yielding wealth management products (WMPs) or other assets, liquidating in time to pay back the LC. Similarly, traders can also use a global copper purchase contract as a way of taking out loans in dollars, which are then changed into yuan to invest in WMPs, taking advantage of the continued strengthening of the yuan against the dollar that many anticipate. Here’s a look at how the trade works when traders well the physical copper on the domestic market, via FT Alphaville:

So as the China economy threatens to slow—and with the central bank declining to pump in liquidity as often as it used to—January’s uptick of copper importing is a strong sign that “cash for copper” is what’s really going on.

Truly worrying are the scenarios that might play out if this trade abruptly unravels. Or, for that matter, what might happen if China’s economy slows more sharply than expected. If it already has an overhang of copper supply to draw on for construction needs, global demand for copper could crater. That could be grim news for Chile, Australia, and a slew of major mining companies.