Shadow banking is the answer to China’s mysterious slump in copper demand

China’s economy is starting to recover and the Chinese government has been approving new infrastructure projects. All good news for global copper demand.

China’s economy is starting to recover and the Chinese government has been approving new infrastructure projects. All good news for global copper demand.

Or at least, it should be. But the link between Chinese growth and copper demand has disappeared of late. While China’s appetite for copper rose for much of last year, the economy was slowing. Then when China picked up speed in October, copper demand fell off a cliff, hitting a 15-month low. That trend has continued: Though the nation’s copper imports rose 14% last year in total, imports fell 6.6% last December on the previous month.

“Last year, China’s economy was slowing and that was combined with de-stocking of inventory. So what seemed very unusual was that for most of last year, copper imports stayed high,” Robin Bhar, head of metals research at Société Générale, tells Quartz. “Those imports should have been falling instead of rising.”

The answer to this conundrum may lie in the fact that Chinese copper demand has increasingly little to do with industry—and much more to do with financing. For much of last year, Chinese companies struggled to get bank loans. Concerned about a huge buildup of bad debts after lending a record 17.5 trillion yuan to economy-boosting infrastructure and property projects in 2009-2010, banks required borrowers to pledge something physical to back up loans. Copper was so popular a choice that copper-backed financing was the “main driver” of Chinese imports for most of last year, as Bhar explains.

“We tend to see commodities, particularly copper, being used to get bank credit at times of monetary tightening in China,” he says. “When we talked to people on the ground in China, the conclusion we came to was that copper was imported not for real usage but to be stored in a bonded warehouse, paying no import taxes or customs duties to act as collateral for loans.”

Last April, for example, China’s warehouses were literally cracking under the weight of imported copper. Borrowers kept the copper in bonded warehouses at ports, meaning they did not have to pay import taxes. The copper was commonly used to back up 180 day letters of credit, a type of short-term loan. At the end of the loan term, Chinese firms sold the copper back into the global marketplace, probably having never seen it.

That need to back up loans with copper is now less strong since credit is suddenly available in China again.

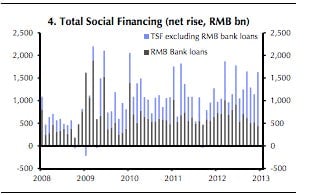

But the copper drop-off also hints at another financing trend in China. Credit is coming less and less from banks, and increasingly from shadowy, off-balance-sheet vehicles—often referred to as “total social financing” in data. As Quartz has reported here and here, China has seen a massive surge in this type of lending, largely via so-called “wealth management products” marketed to retail investors. Then there are “trust companies”—outfits that sell risky, securitized loans to investors from insurers to wealthy individuals. In China, the value of trust loans rose a staggering 697% last December from a year earlier.

This chart from Capital Economics shows how credit suddenly became more abundant in China at the end of last year. It also demonstrates how much of this new credit is coming from outside China’s traditional banking system. Bank loans are falling while social financing is rising.

With few of the concerns for risk-management that banks have, these vehicles have little need for physical collateral, as Bloomberg noted in a story earlier this month—a trend with huge implications for global copper supply. Bhar’s team estimates at there is at least 800,000 tonnes of copper still sitting in Chinese warehouses, mostly having been used to back up loans.

China, it seems, has massive stockpiles of the red metal that companies are likely growing ever-more eager to unload. A worrying trend for anyone betting on a rise in the copper price.